Football Players Union Discusses the National Anthem Protests

A major union representing professional football players discussed activism in sports Monday in response to widespread protest across the league.

The National Football League (NFL) has found itself at the center of attention with some players deciding to kneel during the National Anthem. The players and their supports argue they are using their platform to highlight racial inequality in our society. Those opposed contest that the protest is disrespecting the flag and country.

The National Football League Players Association (NFLPA) discussed the controversy during a union convention in St. Louis. The AFL-CIO, the largest federation of unions in the country, is hosting the annual convention for four days. NFLPA chapter leader Bernard Whittington argued the players have the constitutional right to protest against injustice.

“We look at it like this,” Whittington said during the convention. “We have months for breast cancer awareness. We also recognize our military. Why can’t we recognize the social injustice, the things that have happened to people of color as it related to police brutality? Why can’t we talk about that?”

Whittington is a former professional football player who was born in St. Louis. He played as a defensive end for the Indianapolis Colts and Cincinnati Bengals in a career which spanned from 1994 to 2002. He currently serves as the St. Louis chapter leader for the NFLPA.

The National Anthem protesters have insisted that their aim is not to disrespect the flag or the country. Their intent is to protest in a dramatic way to bring attention to societal problems that are often overlooked. Critics counter that the issue isn’t necessarily what they are protesting but rather the manner in which they are doing it.

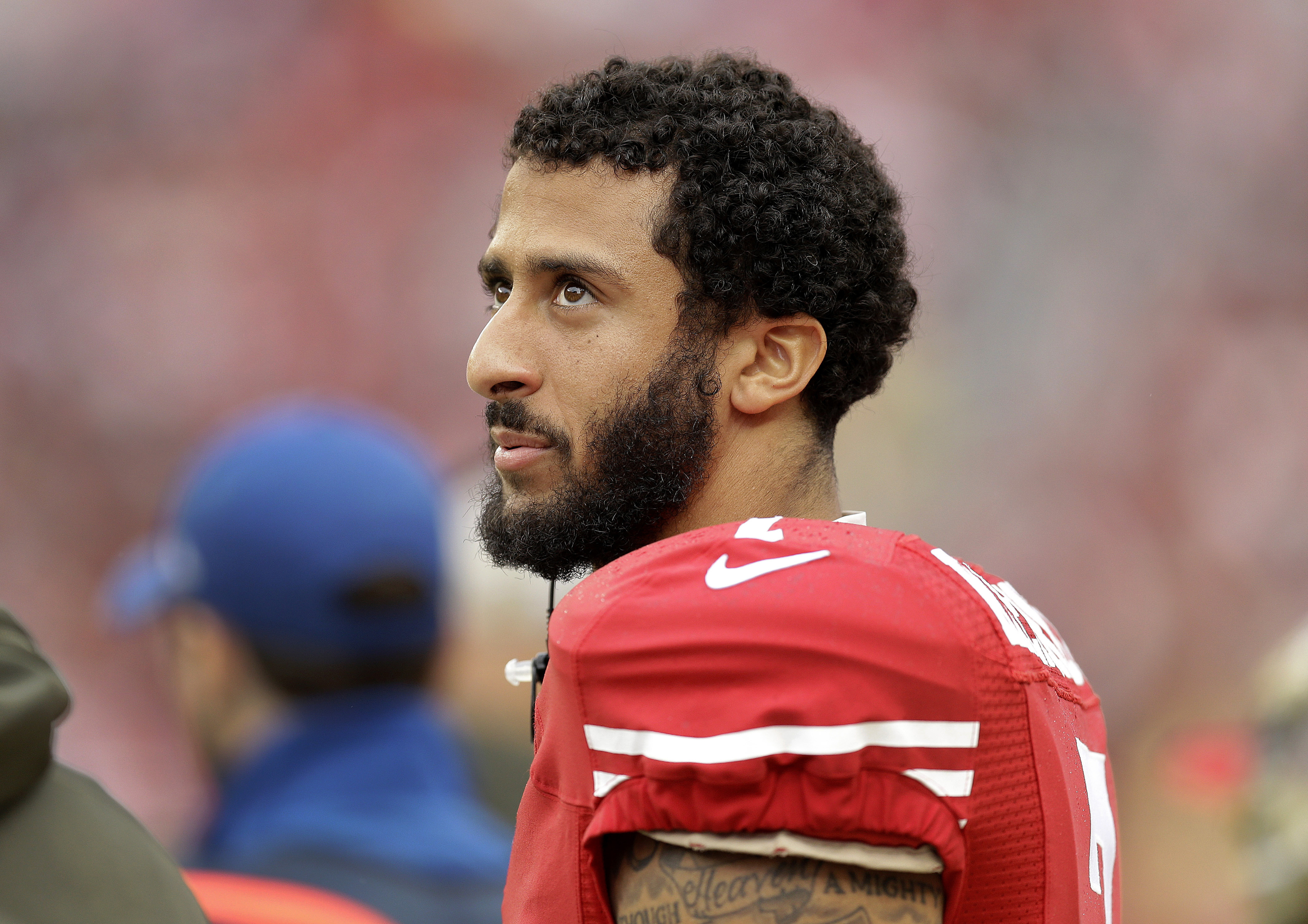

Professional athletes using their platform to protest is nothing new, with examples found throughout the past century. Former San Francisco quarterback Colin Kaepernick helped start the current wave of protest when he started kneeling last year. He was joined by a handful of players, and the protests were able to successfully attract national attention.

President Donald Trump brought renewed interest to the protest when he condemned the players Sept. 22. But his comments didn’t discourage the protests with players from across the league responding by joining in solidarity. Whittington argues Trump’s comments made the situation worse. NFL commissioner Roger Goodell has stated that he will not force players to stand during the National Anthem.

The AFL-CIO convention touched upon several themes that play a critical role in the debate over racial inequality. United Steelworkers President Leo W. Gerard argued that we need to start addressing white privilege. The AFL-CIO called for criminal justice reform that ends mass incarceration while improving working conditions for corrections officers.