When news broke last month that Amazon, the world’s third most valuable company, paid zero corporate federal income taxes in 2018—for the second year in a row—economic populists like Sen. Bernie Sanders wasted no time in calling them out.

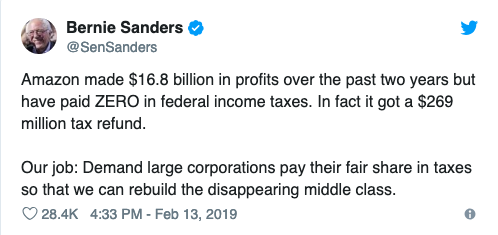

“Amazon made $16.8 billion in profits over the past two years but have paid ZERO in federal income taxes. In fact it got a $269 million tax refund. Our job: Demand large corporations pay their fair share in taxes so that we can rebuild the disappearing middle class,” Sanders tweeted.

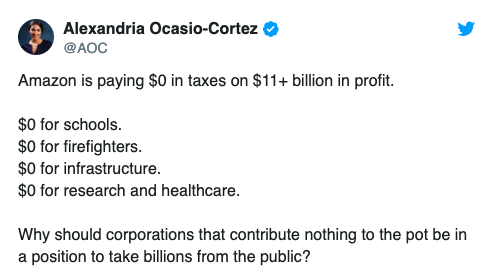

His ideological ally Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez joined in, too:

And to millions of Americans digging through their shoebox of receipts this tax season, the idea of paying out on their meager earnings while the company paid nothing–and got $129 million back–sounds outrageous and even underhanded, especially following a widely publicized Amazon competition that led hundreds of local government officials to offer hundreds of millions of dollars in tax credits and other public subsidies to lure the company to open its second headquarters in their community.

But even if it is inconceivable to many Americans that a global behemoth like Amazon escaped with a tax bill of $0, interviews with multiple tax accountants and policy experts indicate that the company doesn’t appear to have crossed any legal lines, though critics are outraged that corporate accounting gimmicks like those used by Amazon reduce the revenues the government has to make kind of investments in education, transportation and research that make for a stronger economy.

The company’s extraordinary ability to make its tax liability vanish rests simply on its aggressive use of a Byzantine array of tax credits and special deductions, these experts say. In short, Amazon has played by the classic – if distasteful — rules of Washington under the leadership of Jeff Bezos, literally the wealthiest man in the world and one who has gradually made his presence felt in Washington in recent years, most notably with the purchase of the Washington Post.

As a result, critics contend that companies like Amazon have turned the tax code into a corporate handout of massive proportions that has helped it pad its profits. To these critics, such tax-avoidance schemes do little to serve the interest of the American taxpayer, especially since they ultimately starve the government treasury.

“My reaction is that this is another prime example of how Amazon does business,” said Robert B. Engel, chief spokesperson for the Free & Fair Markets Initiative,a corporate watchdog group that keeps a close eye on Amazon. “One of the richest companies in the world is doing something to abuse their power and avoid paying their fair share.”

The news about Amazon’s second successful year of tax avoidance has provoked a major debate among policymakers and experts who recognize that Amazon’s case has raised both political and policy questions about elements of the corporate tax code.

While not blessing Amazon’s tax practices, some experts say that the company is merely playing the tax-avoidance game nimbly, using precisely what the law allows.

“The only people who know exactly how Amazon structured its tax liability are the people who’ve seen their returns,” says tax policy expert Ryan Ellis. “But based on the available information, [Amazon] is doing pretty vanilla stuff. Any first year H & R Block associate could get Amazon what they got.”

“Amazon owed no taxes in 2018 because they deducted research-and-development costs, investment costs, losses from previous years, and employee compensation. They used no loophole,” said Alexander Hendrie, director of tax policy at Americans for Tax Reform.

If not a “loophole,” how did they do it?

“There are a lot of moving pieces that explain it all, but for Amazon there were three big factors,” says Professor Arthur Reed, director of the prestigious Accounting Center for Electronic Learning and Business Measurement (ACELAB) at Bentley University in Massachusetts.

“One is the research and development credit. Another is stock-based compensation which allows a deduction for the simple increase in value of Amazon’s stock. Salaries are ‘capped’ at $1 million per year for tax purposes, but business may provide incentive compensation structures based upon profit, growth, etc. They basically can deduct the increase in value. This is where there is some creative thinking and planning,” Reed told InsideSources.

“And third, companies can use the new bonus depreciation [under the recently-passed tax reform law] where they can deduct the cost of capital assets that they would normally have to deduct over many years. This is called bonus depreciation.”

Add it all together and you have a way to pay no federal corporate income taxes on a huge amount of money that is, Reed says, completely legal. Not everyone agrees.

“Amazon as a company is unique in that their business model is based on gaming the system,” Engel told InsideSources. “When an organization like Amazon makes $11.3 billion and gets $129 million back, it’s a strategy. Amazon is an organization that we’ve seen is obsessed with beating the system.”

“There’s an old saying that ‘there’s no wrong time to do the right thing?’ Well, in Amazon’s world, there is no wrong time to do the wrong thing,” Engel says.

You’ll hear a similar sentiment from Matt Gardner of the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, the organization that first issued the report on Amazon’s net-zero federal corporate tax bill.

“Amazon is a company built on tax avoidance,” Gardner told InsideSources. “I’m a state policy guy and that’s where I first saw Amazon’s involvement in tax policy. In the late 1990s when he was basically in the book-selling business, Jeff Bezos picked Seattle for the company’s headquarters, as opposed to a tech-friendly community like San Francisco. Why?

“Because Washington state has no corporate income tax,” Gardner says. “And then Bezos used the fact that he could sell in many states without collecting sales tax as a business advantage.”

According to Gardner, Bezos sees tax policy as a fundamental part of Amazon’s competitive advantage. “None of it is illegal, just as the [now-defunct] HQ2 strategy for Long Island City, NY wasn’t illegal.”

And the fact that it’s all perfectly legal, Amazon’s defenders say, is the point. Congress has put these tax policies in place because they believe it’s a benefit to the nation’s overall economy for companies to operate under them.

“Amazon is investing in research and development. They’re putting their profits back into the business to create future growth, they’re not just paying off the shareholders for a quick profit. Isn’t that what we want companies to do?” asked Ellis.

“This isn’t just about Amazon,” says Adam Michel of the conservative Heritage Foundation. “Any business, not just big ones like Amazon or Netflix, that is growing quickly and is investing a lot in research and development will pay significantly lower taxes. A lot of small startup businesses don’t pay corporate income taxes because they’re carrying forward operating losses from past years.

“We can have a policy discussion about the research and development tax credit and whether or not it’s good policy, but the idea that Amazon will never pay taxes is just not true.”

And, in fact, a 2017 report by the New York Times found that from 2007 to 2015, Amazon paid federal income taxes year after year, with an average annual rate of 13 percent in total federal state, local and international taxes. Interestingly, that rate is well below that 27 percent average tax rate among S&P 500 companies. Does that fact reflect Amazon‘s “tax policy as competitive advantage” approach?