Amid the public discourse surrounding the passage of the Federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act late last year, one small facet of the legislation was lost in the controversy between who would pay the higher tax rate and the estimated net economic growth that would occur once the law was on the books. Subchapter Z of the law, entitled “Opportunity Zones,” is a provision that directly targets economic growth in the following areas of the country: where the poverty rate is 20 percent or greater, the median family income does not exceed 80 percent of the statewide median family income if located outside of a metropolitan area, or median family income does not exceed 80 percent of the statewide median family income or the metropolitan area median family income — whichever is higher.

These areas span all 50 states in the U.S., and are locations that have specifically been experiencing slow economic growth since the the Great Recession in 2008. According to the Economic Innovation Group (EIG), a D.C.-based think-tank launched by Sean Parker, formerly of Napster and Facebook, these areas make up what are called distressed communities, where household incomes are lower than the U.S. national median of $59,000. According to an EIG report, 52.3 million Americans lived in these distressed communities, which breaks down to one-in-six Americans, 17 percent of the population, or 1/5th of U.S. zip codes, according to 2011-2015 census data.

According to the legislation, state governors are in charge of identifying their states’ Opportunity Zones, and have exactly 120 days from December 22, 2017 to report these zones to the U.S. Treasury (April 21, 2018).

Last week, Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds released a statement calling for communities to submit an application through the Iowa Economic Development Authority (IEDA) to be considered as an Opportunity Zone. According to the legislation, Reynolds, as well as other governors, will only be allowed to designate 25 percent of their eligible areas to receive funds.

“We need to take advantage of all the tools and resources we have at our disposal to spur economic growth,” Reynolds said in a statement. “I am optimistic that Iowa’s participation in the Opportunity Zones Program will serve as a catalyst for investment and job creation and result in prosperity for Iowa communities statewide.”

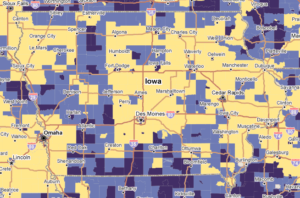

A map of eligible Opportunity Zones in Iowa (blue areas). State’s can only designate 25 percent of these areas as Opportunity Zones. (Photo from PolicyMapy).

The concept of Opportunity Zones revolves around the investment of private dollars for uses that could better communities, by injecting money to areas in the form of business loans and grants, along with construction projects, and other technological updates. According to EIG, which credits itself on creating the premise for the concept in 2015, the idea came as a way to spread the wealth of the economic recovery with areas that weren’t in large metropolitan or coastal cities, which, according to the Brookings Institution, accounted for 73 percent of total job locations from 2010 to 2016. Areas with populations less than 250,000 people accounted for just nine percent of the total job locations during that time frame.

The program advertises itself as advantageous to investors, as its incentives relate to the tax treatment of capital gains, which are tied to the longevity of investors’ stake in an Opportunity Fund. The longer an investor keeps an investment in the fund, the less capital gains tax will be assessed, with a larger return on investment.

Hypothetically, according to EIG, if an investor invests $100 in “unrealized” capital gains from his or her stock portfolio in an Opportunity Fund in 2018, and retains that investment for 10 years, he or she is able to defer the tax owed on the original $100 of capital gains until 2026. EIG states that the basis of the investment is increased by 15 percent, reducing the amount of taxable capital gains to $85, with a total tax of $25 (23.8 percent of $85). Because the investment is tied up for 10 years, according to EIG, the investor will owe no new capital gains on the appreciation of the investment. EIG assumes an annual growth of seven percent, meaning by 2028, the value of the original investment is $176, a 5.8 percent return compared to a 2.8 percent non-Opportunity Fund investment.

The fund can then make loans and investments out to communities, where the money can be used to start news businesses, upgrade technology infrastructure, as well construct needed physical buildings.

While this portion of the Federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was not talked about much in the proceedings of the legislation, it had bipartisan support in the form of the Investing Opportunity Act, sponsored by New Jersey Senator Cory Booker (D) and South Carolina Senator Tim Scott (R) in 2017. The program was expanded in the most recent tax legislation.