Newly-installed South Korean President Moon Jae-in is really shaking things up. Swept into office on the heels of a corruption scandal, he’s wasting no time shaking things up. Like U.S. President Donald J. Trump, Moon has gotten the greenlight from voters to take on entrenched interests aggressively and change the way business is conducted.

One of his first acts was picking Kim Sang-jo – also known as the “Chaebol Sniper” – to serve as antitrust regulator. “Chaebols” are the sprawling, diverse enterprises like Samsung, LG and Hyundai that are deeply entrenched in Korea’s economy. With Samsung’s vast holdings and operations alone representing close to one fifth of South Korean GDP, many chaebols are regarded as “too big to fail.” Simply letting them alone though is not what many Koreans want.

These enterprises have long maintained close ties with the government, in some cases too close. In fact many believe that the millions of dollars in charitable contributions made by chaebol leaders to allies of former President Park Geun Hye were encouraged or even directed by the government – contributions that led to her impeachment and ouster and to the indictment of Lee Jae-yong, the heir apparent at Samsung.

Korean millennials presume an economy dominated by these behemoths cannot provide them with economic opportunities and choices. The chaebol system stokes their resentment of privileged elites.

The voter critiques evident in the last election may be well-grounded but they need to brace themselves for dramatic and lasting implications of a wholesale pivot from practices that have gone on for decades. Whatever criticism is warranted Korea’s phenomenal economic growth turned it from a war-shattered, Third World country to a regional, even global powerhouse in just 50 years in part because of these industrial giants. Moon should resist turning a sniper on the chaebols at a time when change is already in the air.

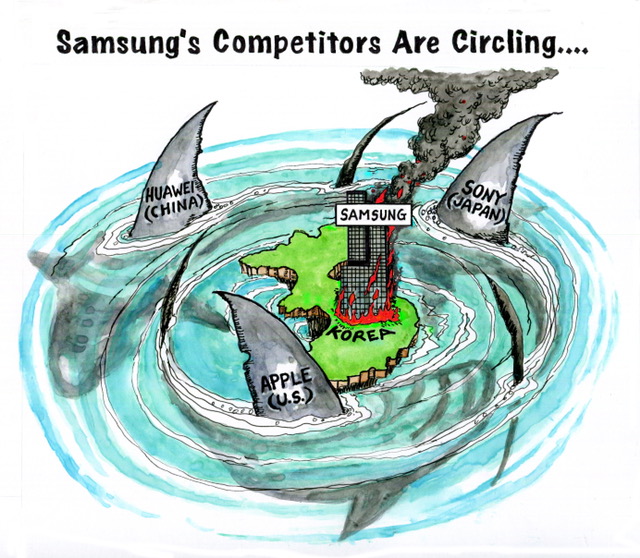

There’s little room for error when it comes to the high-stakes competition in the consumer electronics sector. Apple, one of Samsung’s main rivals, has a quarter trillion dollars in the bank or so it was recently reported. That’s a lot of cash to deploy in countless ways to stay a step ahead in design innovation and marketing. Fortunately for Apple this is a time of relative tranquility at the company under Tim Cook. The opposite is true at Samsung where Jay Y. Lee’s arrest and trial has left a gaping leadership void.

Foreign Investors are also watching closely. Moon’s revolution could lower stock values, attracting a wave of investor activism. Chaebols such as Samsung and Hyundai, which are family enterprises, might have to come to terms with having more strangers in their inner sanctums. Subtle changes in consumer demand and competitive pressures will have an impact on their ability to stay on top.

Anyone who believes the mighty cannot fall should look no farther than Sony. For many years, the name Sony was synonymous with state-of-the-art electronics. The 90s digital revolution exposed the tensions between Sony’s media division and its engineers over how to package and sell music. This delay in timely innovation and gave Apple an opening to figure out how to connect devices with market dynamics in the form of the iPod and then the iPhone. After years of sharp losses and sagging profits, a tough restructuring plan appears to have put Sony back on its feet but it’s just not the company it once was. Sony and other Japanese electronics companies could benefit from Korean setbacks.

We should wish the South Koreans success as they embark on this exercise in “creative destruction.” Like the Americans who put Donald Trump in the White House because they were fed up with a system that no longer served their interests, the South Koreans want change. By taking aim at Korea’s economic model, President Moon, like President Trump, is showing is he not afraid of a making waves as a means to implementing reforms to the Korean business culture. Beware of sharks along the way.