Are Plastic Pipes for Drinking Water a Better Alternative?

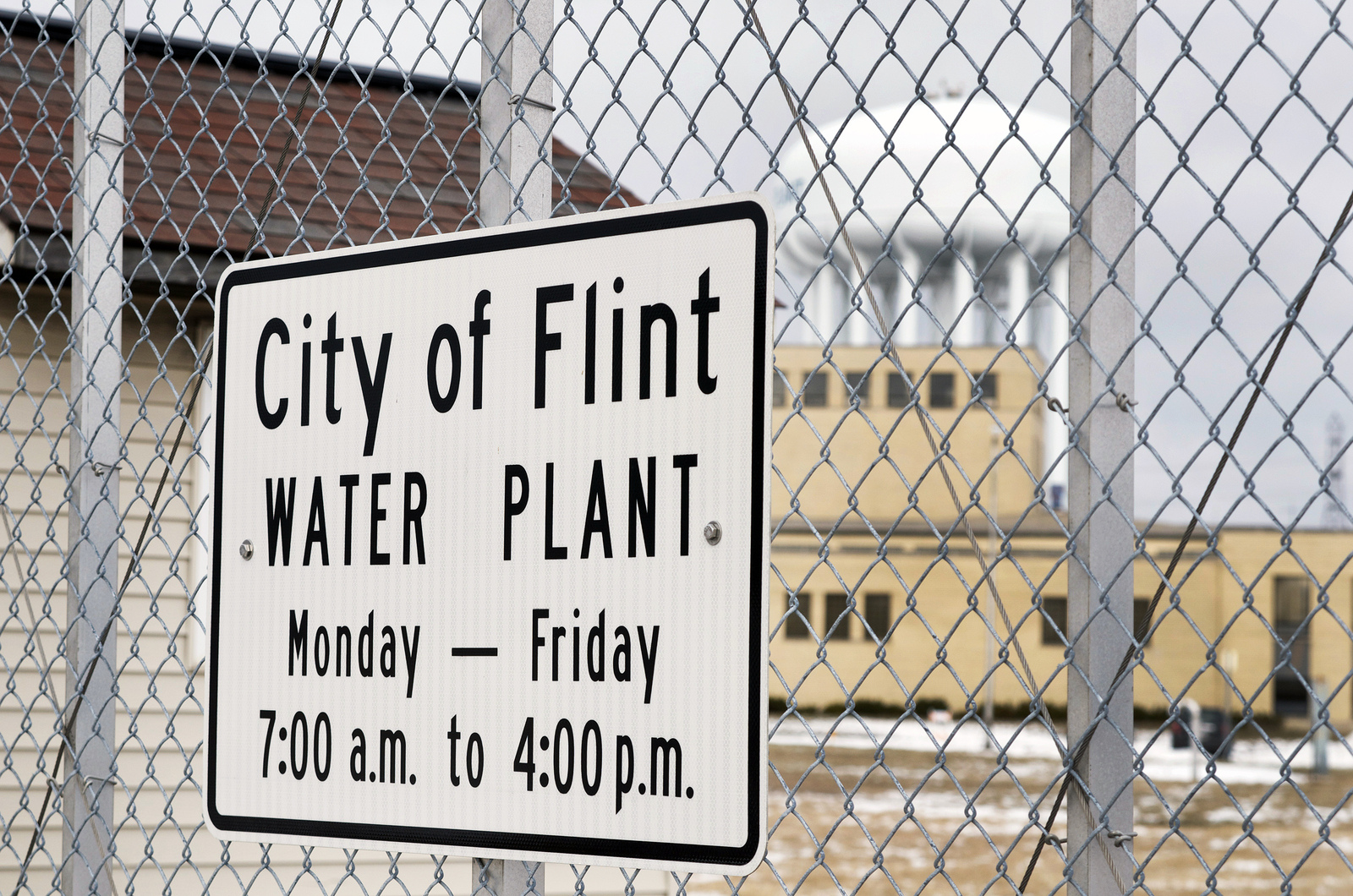

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — After the Flint, Mich. lead water crisis, cities and towns across the country are looking to replace their drinking water pipes. Many communities are looking at plastic pipes as a safe, easy, cost-effective solution. Yet, the alternatives might not be as safe as people think. Two experts detailed the possible health risks plastic pipes pose at a public meeting in Cambridge, Mass. on Tuesday.

The city just across the Charles River from Boston is starting the process of replacing their old pipes, which have been around for more than 100 years. The Cambridge Water Board held an open forum at the Walter J. Sullivan Water Treatment Facility and invited Andrew Whelton, environmental engineer and professor at Purdue University, and Joan Ruderman, a biologist and member of the National Academy of Sciences, to discuss their research with residents.

Cambridge is looking to implement cured-in-place-pipe (CIPP) water infrastructure repair technology to replace their current pipe system. CIPP involves felt liners being injected with resin and cured inside existing pipe, essentially a pipe-within-a-pipe.

“Plastics are being used across the country for a number of different technologies,” Whelton said, and they’re commonly being used for drinking water pipes “because you don’t have to dig up and remove that pipe. You chemically manufacture a pipe within a pipe.”

The technology has existed for several years, but cities and towns have only recently started implementing CIPP in their water systems.

While there are benefits to replacing existing pipes with plastic, like an improvement in water pressure or better water clarity, it is possible for the CIPP technology to fail, leading to negative health effects. In some of his research, Whelton found that the plastic pipes, which are supposed to last between 20 to 50 years, only lasted for nine years.

“What happened was when they [piping contractors] went in to spray the plastic coating, the plastic coating basically didn’t have the strength and slumped down to the bottom of the pipe,” he said. “You’re supposed to see equal thickness of coating around the pipe.”

When that happens, Whelton said, the chemicals could leech into the drinking water that goes to businesses, schools, and households. The chemicals mixing with the water could be used by organisms to grow; it can transform into disinfected byproducts not meant for human consumption, and it can change the pH level of the water making it not safe to drink.

The material that is used to create the plastic pipe is usually an epoxy resin, which is mostly made from bisphenol A (BPA), commonly found in most household objects like eyeglasses, DVDs, and water bottles. The negative health effects of BPA on humans has been well-documented, leading many companies to create BPA-free objects.

Ruderman said BPA has the potential to mimic estrogen in women, interfere with testosterone, and lead to abnormal prostate growth or changes in mammary glands, which could lead to cancer.

“The effects of BPA on human development, fertility, cancer, and behavior are only just starting to be understood,” she said.

The problem is that there aren’t enough studies being done in the United States to seriously examine what health issues could arise due to BPA from plastic pipes leeching into drinking water.

Ruderman said there are some countries in Europe, including Germany and Sweden, that have restricted or discouraged the use of epoxy-based materials in drinking water pipes. However, they are commissioning more studies on the health effects than the United States.

“The plastic industry has done a terrible job about identifying the chemicals that leech out into the water and understanding what happens to them, at least publicly,” Whelton said.

There hasn’t been any complaints or issues of lead contamination in Cambridge’s water supply, but a Boston Globe report published on the same day as the meeting found that more than 1,000 Massachusetts schools had at least one sample showing lead levels above regulatory limits, with some cases rivaling or exceeding levels measure during the crisis in Flint. The Massachusetts Public Interest Research Group recently gave the state a “D” letter grade for its efforts to prevent lead from entering the water at schools and day-care centers.

The District of Columbia is still grappling with lead contamination in drinking water. A Flint whistleblower told InsideSources last year that D.C.’s lead water crisis between 2000 and 2004 would have a long-term impact that’s significantly worse than what happened in Michigan. Yet, lead pipes remain in the system.

If Cambridge decides to move forward with CIPP, Whelton said the city should come up with specific requirements and tests that contractors should meet in order to implement the technology. He suggested they hear bids from several companies and to push back if the contractors try to make any changes to their plans.

Residents who attended the meeting had concerns about the potential health effects of the CIPP technology, asking why the city would move forward on this even if there was just one concern about the health impacts of the plastic pipes. Others said they would be willing to pay more taxes to implement a better system that wouldn’t involve plastic.

Ann Roosevelt, president of the Cambridge Water Board, tried to assure residents that this was only the first step in a long process before the city approves of any project.

While the experts at the meeting focused on the possible health effects of CIPP technology, there was no speaker who advocated to keep the pipes the city currently uses. Plastic pipe representatives were sitting in the audience, but largely remained quiet during the whole discussion.

Attendees were able to voice their opinions during the Tuesday forum, but when someone asked if city residents would get to vote on the measure, Roosevelt said they would ultimately not get a say in the matter since the Water Board is given statutory power to make its own decisions.