Opponents of the Biden administration’s reinvigoration on antitrust enforcement claim that applying antitrust law will lead to a slowdown in economic growth. For example, Larry Summers, who served in the Reagan Council of Economic Advisers and the Obama National Economic Council, tweeted that “hipster Brandeisian antitrust, with which the Admin and its appointees flirt, is more likely to raise than lower prices” and “lead to reduced supply.” He also tweeted, “Brandeisian populist antitrust policy will make the U.S. economy more inflationary and less resilient,” and “may reduce efficiency.”

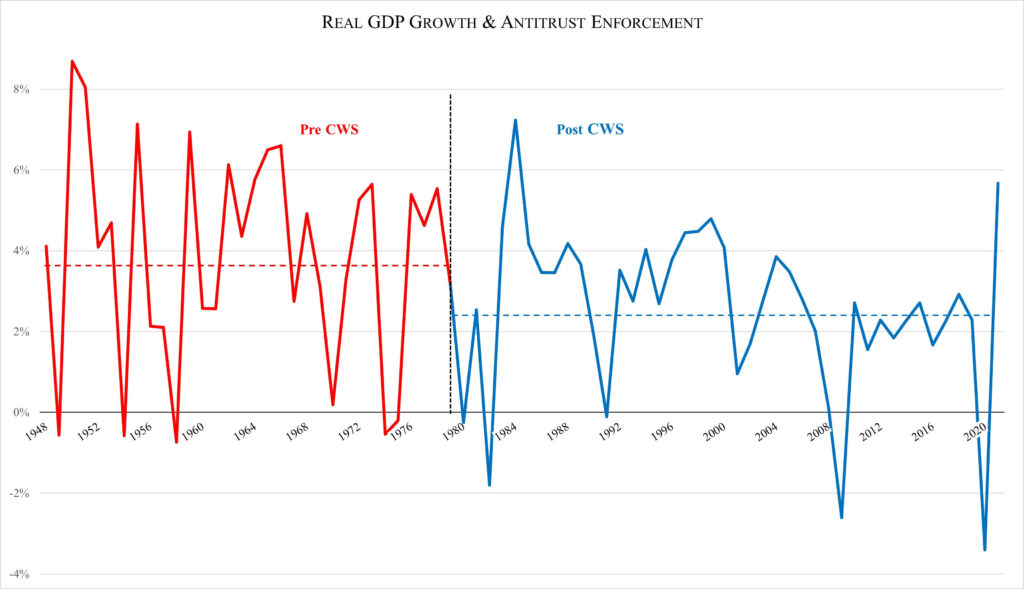

Is stringent antitrust enforcement bad for the economy? To answer this, I gathered economic growth data from 1948 (the earliest available) to the present. I mark the cutoff date as 1980, with the embrace of the consumer welfare standard (CWS) under the Reagan administration, which marked the end of vigorous antitrust enforcement.

The red line in the attached chart shows real GDP growth in each year before 1980, before the adoption of the CWS standard. The blue line shows real GDP growth from 1980 onward, as the CWS standard was embraced by subsequent administrations, including Democratic ones.

The red dashed line is the average real GDP growth in the pre-CWS era, equal to 3.86 percent. The blue dashed line shows the average real GDP growth in the post-CWS era, which is 2.56 percent. The difference in the two means is economically significant (over 1 percentage point of growth) and is statistically significant at the 5 percent level.

Clearly, myriad factors affect real GDP growth. And adoption of the CWS standard may not have been directly responsible for the decline in average real GDP growth since 1980. But it is disingenuous for defenders of the antitrust status quo such as Summers to claim that abandonment of CWS will result in a parade of horribles for the economy. Economists (including myself) have shown that both labor productivity and total factor productivity declined significantly with adopting the CWS. We have noted that greater antitrust enforcement could stimulate economic growth, particularly to protect workers. As income shifts toward workers and away from capital, each dollar of revenue generated at a firm is attached to a higher multiplier effect, leading to faster growth. Economic theory and empirical analysis suggest that embracing a more vigorous antitrust policy could benefit the U.S. economy.