If classical economics has taught us anything, it’s that trade is unquestionably beneficial to mankind. As Adam Smith observed, trade allows for specialization, which increases efficiency, reducing prices and increasing standards of living. It also provides people with access to commodities that may be difficult or even impossible to obtain where they live. While the results may vary at the individual level—a farmer who tills stony soil to obtain a meager amount of grain might find himself put out of business by a merchant carrying an abundant supply from a more fertile region—it is undeniable that, from the perspective of material wellbeing, trade is welfare enhancing in the aggregate.

However, there is another alleged benefit of trade that has been proclaimed by its proponents for centuries. Immanuel Kant believed that free trade would be integral to the task of perpetuating peace. British MP Richard Cobden claimed that free trade would unite the world “in the bonds of eternal peace.” And French thinker Frédéric Bastiat argued that there would be no need for standing armies or navies if trade were free. These beliefs have been echoed in recent years by op-ed writers from the CATO Institute to the Christian Science Monitor. The foundation for this set of claims is that trade provides an alternative (and often cheaper) means of acquiring what is desired. As Norman Angell reasoned, trade has the potential to render the acquisition of property through war unprofitable.

Although the assumption that trade is inherently advantageous is a sound one, it is important to realize that this applies only to those states that are involved in the transaction. When a buyer and a seller conclude a transaction, both have been made better off. However, the satisfaction of the buyer’s demand for the seller’s commodity removes—at least temporarily—one potential buyer from the market. In other words, the market for the seller’s competitors’ products has shrunk, if only slightly. Thus, while trade enhances the welfare of traders, it has the potential to decrease the welfare of others in the marketplace, and to introduce tension between competitors. While the pacific benefits of trade extend only to the traders, the transaction may incite conflict among others whom it affects.

This is the point made by myself and a colleague (Kerim Can Kavakli from Sabanci University) in a recent paper that examines export similarity and conflict propensity. We argue that this is neither a trivial point, nor a strictly academic one. Indeed, the mercantilist era of Europe’s history (from the 15th through 19th centuries) was replete with conflicts that emerged from “commercial rivalries,” in which states fought each other over colonial holdings that provided them with natural resources for manufacturing, as well as markets for the finished goods. Despite the fact that classical economics had largely trumped mercantilism as a school of thought by the 1800s, neo-mercantilist thought exists even today, among policymakers (in the U.S. and elsewhere), business leaders, and a number of public intellectuals.

We argue that the persistence of this zero-sum mindset has allowed trade to continue to exert negative, in addition to positive, effects. To examine our theory, we have constructed a measure of export portfolio similarity. This is the degree to which a pair of states (which we call a “dyad”) relies upon the same commodities for export. Thus, OPEC states, which tend to export mostly oil are coded as being highly similar, while states that rely on primary commodity exports and have very different resource endowments (such as Iraq and Burundi) are coded as being very different. We then look at the likelihood that a dyad becomes involved in armed conflict, given its level of portfolio similarity.

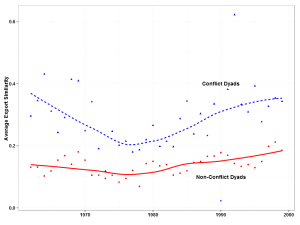

As the figure above shows, dyads that experience conflict tend, on average, to have more similar export portfolios than dyads that remain at peace. With one exception (caused by the Iraq War in 1990), the average level of export similarity is universally higher for dyads that go to war. We find that this relationship continues to hold, even when we account for factors such as distance and shared borders, which could potentially affect whether states sell similar goods.

Perhaps more interesting than our finding that export similarity is related to conflict is that the effect of trade appears to be conditional upon portfolio similarity. For competitors (dyads that export similar goods), trade does indeed have a pacifying effect. However, this effect diminishes as the states’ portfolios diverge, with trade actually associated with a marginal increase in the likelihood of conflict for states with very different portfolios. We believe that this is a result of the dual effects of trade. On one hand, it is a positive interaction that can assuage existing tensions (from competing in the global marketplace, for example). On the other, it expands the set of issues over which a dyad might disagree, spawning potential conflicts where there were none before. This latter effect is especially likely for pairs of states that had few or no prior interactions. Whether trade is peace-inducing or peace-inhibiting seems to depend strongly upon the dyad’s preexisting relationship.

International trade has obvious benefits for those involved, and it is desirable from the standpoint of maximizing material wellbeing. However, while the argument that it leads to peace is intuitively appealing, it does not seem to be quite that simple: trade reduces conflict only sometimes. Moreover, we should always be aware of the dangers of unforeseen externalities. Even if trade is, in fact, conflict-inhibiting for a pair of states, it has the potential to spark disputes elsewhere. Advocates of free trade should emphasize its ability to reduce poverty and to enhance the quality of life of people everywhere. But they should be wary of arguing for its adoption on the grounds that it will lead to world peace.