Last summer, Native American environmental activist Winona La Duke took to the internet to ask for donations to support an organic hemp farm that she wished to start. Several months later, she resurfaced to push to halt the permitting process for the Enbridge Line 3 project, which would run through northern Minnesota. Now La Duke has returned to her hemp project, again pushing for donations to her industrial hemp farm, which she claims contains some of the keys to a new green economy.

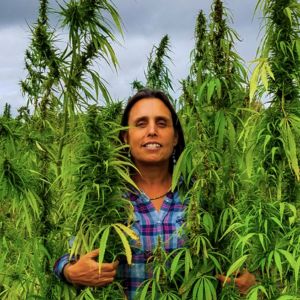

“I have made a commitment to grow the future, to grow hope. Here at Omaa Akiing … we are doing that,” La Duke said in a resent Instagram post, which shows her flanked by hemp plants eight to nine feet tall.

The plants demonstrate the partial success of La Duke’s project. Last year, she began to solicit donations to fund the planting and cultivation of an industrial hemp farm, which would raise the plant for its fiber, seeds, and oil. Now, the operation has grown and includes eight acres of hemp under cultivation. Throughout its existance, Winona’s hemp farm has benefited from the generosity of donors, who have largely funded the purchase of the land and equipment needed to operate the hemp farm.

“A generous donation from Project Earth has moved us towards purchase of a small decordicator [a machine for stripping off of the stalks in preparation for processing],” La Duke wrote in an update on her farm’s blog.

Her original plans emphasized that the hemp farm would use only horse-drawn equipment, which was seen as closer to nature and the current iteration of Winona’s Hemp Farm still uses teams of horses to help pull some farm instruments. They may, however, need a small tractor to use some of the implements necessary to process the hemp they grow.

In her posts, La Duke does not mention any shift in strategy, but instead continues to reiterate the need to return to native ways to find a spiritually and ecologically regenerative form of agriculture. Hemp, she says, will play a key role in this, replacing both cotton (which requires large amounts of water to grow), and synthetic materials as the main material used to make clothing.

“The hemp is ready to come back to our economy and Omaa Akiing here on this land. I want to make rope for all of us–whether Sun Dancers, or sailors; and I want to make fabric- because this is the fiber of the past, and the future,” she writes.

Although hemp clothes are her vision of the future, they aren’t yet a reality. Despite the progress that has been made, Winona’s Hemp and Heritage Farm, as the operation has come to be known, is still a long ways away from being a self-sustaining agricultural operation. Now that hemp is planted, the farm is in need of a facility to process the crop. Today, the largest processing plant for industrial hemp in Minnesota is in the west-central town of Olivia. La Duke, however, wants to build a processing plant of her own by purchasing a building in the nearby town of Callaway, MN.

“I am looking to a building–a building where the work of making rope, making thread can come to be. This is my next hope- to purchase the building within which we will house our thread and rope making factory,” she wrote in a recent blog update.

To purchase the building, she is looking to raise some $81,000.

In addition to her agricultural project, LaDuke remains involved in the fight to halt construction of the nearby Enbridge Line 3. She sees the two projects as parts of the same struggle towards a regenerative economy, which more highly values native agricultural and ecological knowledge, and which puts a greater emphasis on avoiding environmental harm

Although generally known today for its connection to illicit drug use, hemp was grown in the past for various industrial uses, including oil, food, and fibers. Hemp was once a common cash crop in southern Minnesota, but farmers transitioned away from more than 70 years ago when market conditions made it unprofitable.