For teachers and librarians, returning to school means getting students back to stories. Stories matter, and they make a difference in our lives. Often, the jarring stories are most magnetic and make lifelong readers.

An angry little boy sent to his room for punishment finds it transformed into a jungle with monsters (and feelings) he conquers (“Where the Wild Things Are”). A formerly enslaved woman and her family are, literally and metaphorically, haunted by the murder of her child and the horrific circumstances that led to it (“Beloved”).

These stories and many others teach us important lessons about humanity.

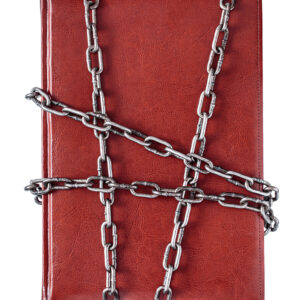

Stories allow us possibilities: to step into the shoes of a character from the distant past or someone distanced in the present because their path doesn’t conform to the reader’s experiences. This year, these possibilities are diminished by the widespread removal of books from classrooms and libraries across the country.

Disproportionately, the stories most under scrutiny involve characters and authors who are Black, Indigenous or Persons of Color, and/or who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex or asexual.

Because of legislation in states like Florida, Tennessee, Oklahoma and Missouri, and the continuing onslaught of local book challenges, students will have less to read this year. That should concern us all.

Increasingly, some people in communities across the country, often spurred by disinformation and politically motivated groups, wish to ban books in the name of parents’ rights. That’s a red herring. Teachers and librarians have always respected the rights of parents to decide which books their children read. We work closely with parents to help them make those choices, including offering alternate book options. It’s the purpose of schools and libraries, with the professional expertise of educators and librarians, to offer a wide range of perspectives and increase understanding of different backgrounds.

But no one has the right to dictate what books other people’s children are allowed to read.

Young people deserve healthy models for discussion, not an antagonistic approach that vilifies teachers and librarians and divides communities. In Tennessee classrooms, students cannot borrow books until teachers have compiled, submitted for review, and posted lists of books in their classroom libraries. For now, a student who asks to grab a book from the shelf will likely be told “no.”

Students in Brevard County, Fla., arrived to find classroom libraries labeled “under construction,” a code phrase for “off limits.” Across the state, in Sarasota County, school libraries are prohibited from purchasing new books until at least January 2023.

Teachers and librarians in Keller, Texas, were ordered to remove all books that had been challenged during the previous school year. And in Missouri, school librarians are required to preemptively remove books from shelves under threat of criminal charges because of a new law.

When students head toward public libraries after school, they’ll face the same challenge, with attempts to remove books in public libraries across the country.

Banning a book — or burning it, as politicians in Tennessee and Virginia have proposed — does not extinguish its truth. Ours has always been a nation of many stories, and to silence some is to diminish opportunities for our students to both build understanding of what it means to be fully human and to see themselves represented in what they read.

By banning books, we pass down the practice of silencing onto children and teach young learners that when a difference in opinion arises, snuffing out opposing views is justifiable and that some people’s lives and experiences are unimportant.

Book bans should not be the default option for dissent in our classrooms or libraries. Those who value the freedom to read need to be as organized as those who seek to curtail it. That’s why we stand together in the fight against censorship with a growing list of individuals — authors and publishers, educators, parents, civil rights groups and more.

As we come back together in classrooms and libraries, we call upon school boards, parents and concerned citizens to model civil discourse by encouraging serious discussion about complex and competing ideas through books. In the process, maybe we’ll all learn something.

Valerie Kinloch is president of the National Council of Teachers of English and the Renée and Richard Goldman Dean of the University of Pittsburgh School of Education. Lessa Kanani’opua Pelayo-Lozada is president of the American Library Association and a librarian at Palos Verdes (Calif.) Library District. NCTE and ALA are founding partners of the Unite Against Book Bans campaign.