A spending proposal in President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better plan would deny funding for students who choose to attend private-sector career colleges, rather than public community colleges. It’s a burden that would disproportionately fall on veterans, older students, and people of color.

“We think it’s unfair and it’s unjustified,” said Dr. Jason Altmire, President and CEO of Arlington, Virginia-based Career Education Colleges and Universities (CECU). “This has not been done before in the Pell Grant program.”

For decades, low-income students have relied on Pell Grants to access higher education. Biden’s proposal would increase the maximum Pell Grant by $550 (to $7,045), which would fully cover the average cost of in-state tuition and fees at public community colleges in 48 states for students receiving the maximum award, according to the center-left group Third Way.

But while current funding levels would continue for the 900,000 Pell recipients attending career colleges, the White House’s plan would exclude them from the increased BBB funding. That would be a troubling break from traditional education grant funding, which has always followed the student, critics say.

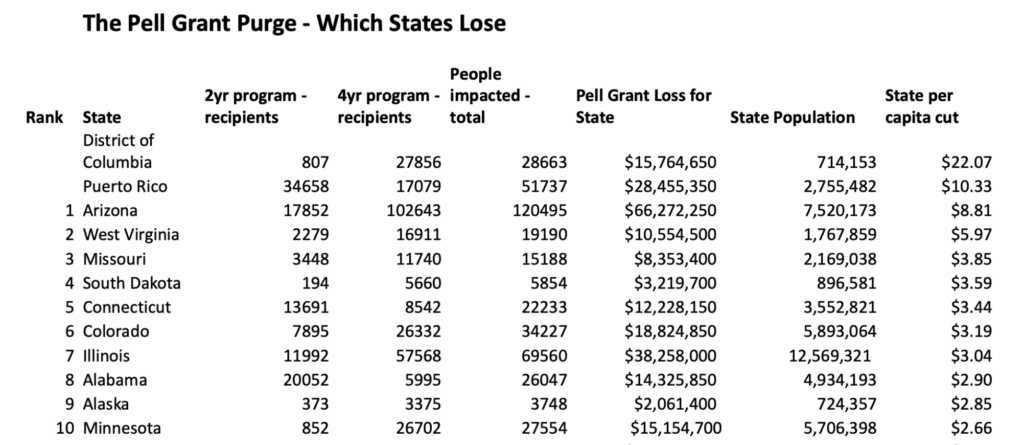

It would also hit West Virginia and Arizona hardest. Arizona would suffer the highest per capita funding loss in the country under this Pell Grant policy, with West Virginia at number two.

“We are working very hard with both Republicans and Democrats to carry that message that this is unfair, it’s unprecedented and we support what’s best for our students which is equality in the Pell Grant program,” Altmire said.

Career colleges, which place a greater focus on job skills and workforce qualification than traditional colleges, tend to be more popular with non-traditional students, such as older students and military veterans. Career college students are also disproportionately people of color.

“There’s a lot of reasons why people might choose that type of setting,” said Altmire, a Democrat who represented Pennsylvania’s 4th Congressional District from 2007 to 2013. “Reasons include more flexible hours, or they just like the campus or the program. Some prefer the classes because they’re more intense and they’ll finish more quickly and get back in the workforce.”

During the Obama administration, the Department of Education also tried to restrict federal funding for career college students. Some in the education community believe it’s because progressive elements in the Democratic Party are ideologically opposed to the for-profit model. They support policies like a proposal backed by Sen. Bernie Sanders (D-Vt.) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) to spend $109 billion on free community college for everyone.

That proposal was stripped from the version of the Build Back Better bill passed by the House in November.

One outspoken career college opponent is Robert Shireman, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, a liberal think tank, and a former member of the Obama Department of Education.

“For-profits have over many decades been associated with scandals and students being ripped off,” Shireman told The Washington Post. “Every time the government tries to institute controls, the for-profit institutions claim they are being targeted. They fight it or undermine it by adding loopholes.”

Shireman left his job in the Obama Department of Education “under an ethical cloud,” according to a government watchdog organization, after leading the administration’s attacks on career colleges.

In fact, data show career colleges have a median completion rate that is twice as high as public career colleges.

“We produce half the truck drivers in the country,” says Altmire. “So, if you want to talk about the supply chain and the issue associated with the shortage of truck drivers, I don’t know how they think they’re going to solve that problem by disincentivizing people from going to those types of schools.”

The National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators (NASFAA) also objects to restricting these grants.

“While a $550 increase to the maximum Pell Grant is a welcome upfront investment toward making college more affordable for low-income students, we are concerned to see these funds parceled out by institutional sector, which will add new complexity to a financial aid system on the verge of much-needed simplification,” NASFAA President Justin Draeger said in a recent interview.

“The best place to address concerns about institutional quality at some proprietary institutions should be in the institutional eligibility and accountability provisions in the Higher Education Act, not by making programmatic changes that add complexities to students.”