Originally posted at Josiah Barlett Center for Public Policy

Many people believe that cutting tax rates always and automatically lowers government revenue. They believe this even when shown that it isn’t true.

When House Bill 10, a bill to continue reducing the Business Profits Tax and Business Enterprise Tax rates, had its turn in the House Ways & Means Committee on Thursday, the predictable objection was made. Opponents said it would reduce state revenue.

But this prediction was made before every business tax rate cut in the last five years. It has yet to prove true.

In 2015, Gov. Maggie Hassan predicted that the business tax rate reductions put into place by the Legislature starting in the 2016 fiscal year would blow a $90 million hole in the upcoming two-year state budget.

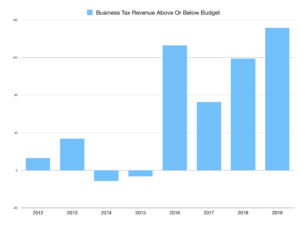

To quote Harry Doyle, that prediction was just a bit outside. Business tax revenues were $132.8 million (23.4%) above plan in FY 2016 and $72.7 million (12.9%) above plan in FY 2017. Instead of a $90 million budget hole, the state wound up with $205.5 million more than planned.

The trend continued for the next two years. Business tax revenues were $118.8 million (17.9%) above plan in FY 2018 and $151.6 million (23.2%) above plan in FY 2019.

In those four years, business tax revenues exceeded budget projections by a combined $475.6 million.

So after the state began cutting business tax rates, business taxes generated almost half a billion in unplanned revenue in just four years— an enormous windfall.

But what about the four years before? Surely the economy, and with it state revenues, were growing rapidly before the tax cuts.

Business tax revenues were $13.1 million above plan in FY 2012, $33.7 million above plan in 2013, $11.5 million below plan in 2014, and $6.5 million below plan in 2015.

After the state cut business tax rates, business tax revenues took off like a cheetah that wandered into a Nigerian hacker hangout and ransacked the entire stash of Red Bull.

In 2017, the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant projected that the additional business tax rate reductions passed in 2017 would cause an $11 million reduction in business tax revenues in FY 2019. Business tax revenues came in $151.6 million above plan that year.

It would be a mistake to attribute all of those revenue gains to the state business tax cuts. Other factors, such as national economic growth and federal tax changes, played a large role, as the Sununu administration has pointed out.

But one also cannot attribute all of those gains to the national economy. From 2016-2019, the U.S. GDP grew by 9.3%, while New Hampshire’s grew by 11.6%, according to Federal Reserve figures.

Not long ago, New Hampshire had the highest business tax rates in New England. Thankfully, that is no longer true, though our rates are higher than notoriously high-tax Rhode Island and Connecticut.

Despite recent reductions, our business tax rates remain very high. We are near the bottom — 41st in the country — in the Tax Foundation’s ranking of corporate tax rates.

High business tax rates have been shown to have a negative effect on business startups, job creation, productivity, and economic growth. Pushing New Hampshire’s high rates down a bit more would, at the very least, increase our economic competitiveness and make us more attractive to employers. It also would improve the atmosphere for small-business startups.

As the state’s experience since 2016 shows, it is a mistake to assume that further business tax rate reductions would trigger automatic state revenue reductions. All recent predictions that this would happen have proven false.

Drew Cline is the President of the Josiah Bartlett Center for Public Policy