Good fences make good neighbors, but do good neighbors make good POTUS nominees?

A fascinating new analysis by the data geeks at FiveThirtyEight finds a strong correlation between proximity and performance for candidates in the New Hampshire presidential primary. How strong?

Starting with Sen. Ed Muskie (D-ME) in 1972 and continuing through Bernie Sanders’ big win in 2016, every single major POTUS candidate from a neighboring state either won the New Hampshire primary or came in second. Every. Single. One.

As FiveThirtyEight’s Nathaniel Rakich writes:

“Of the nine [major candidates], six finished in first place, and three finished in second. In other words, when politicians from neighboring states contest the New Hampshire primary, they win it 67 percent of the time, and impressively, they have always finished in the top two. Needless to say, that’s a remarkable batting average.”

Veteran Democratic political strategist Joel Payne isn’t surprised. “I worked for John Edwards in 2008,” he told NHJournal, “and even as a relatively junior staffer at that point, I never understood why we would contest New Hampshire. We had a candidate that did not sound like New Hampshire, think like New Hampshire or play well in New Hampshire.”

Michael Barone, longtime co-author of The Almanac of American Politics, agrees that there’s a “New England culture” connecting residents across the region. “It extends not quite to Fairfield County, CT. Its western fringe, populated in the 1970s and 1980s by New Yorkers and culturally-compatible liberals (Bernie Sanders, Howard Dean), is now its most leftish area outside Cambridge,” he told NHJournal.

So is there a New England advantage in New Hampshire? As GOP consultant Dave Carney said of these stats, “The facts are hard to argue with.” The question is why? Is it the case that Granite State primary voters backed Mike Dukakis and Mitt Romney just because they were locals? Or put another way, would John Edwards and Newt Gingrich have finished first in New Hampshire if they’d been from Down Maine instead of down south?

Rakich lists several facts that likely contribute to this home field advantage:

- 84 percent of New Hampshire’s population gets Boston TV stations. The rest are in either the Portland or Burlington media markets.

- 25 percent of New Hampshire residents were born in Massachusetts.

- New England is also physically small, with six states packed into an area smaller than South Dakota.

- New Englanders share a cultural and political identity: colonial heritage, reverence for town government and love for Dunkin’ and the Red Sox.

Then there’s the “chicken vs. egg” question: Do New England politicians decide to run for president because of their proximity to New Hampshire?

But while access might breed ambition, it doesn’t ensure success. Of the four major-party nominees from Massachusetts since WWII (JFK, Dukakis, Kerry and Romney), only one made it to the White House. (George H. W. Bush ran was born in MA, but ran as a Texas oilman.)

This nine-for-nine number could be a coincidence. Reagan won big in New Hampshire, Pat Buchanan was a surprisingly strong 2nd-place finisher in 1992, and the Granite State is widely viewed as having rescued the endangered candidacy of Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton that same year. Their success was based on their ideology, their message and their political talent. The map only means so much.

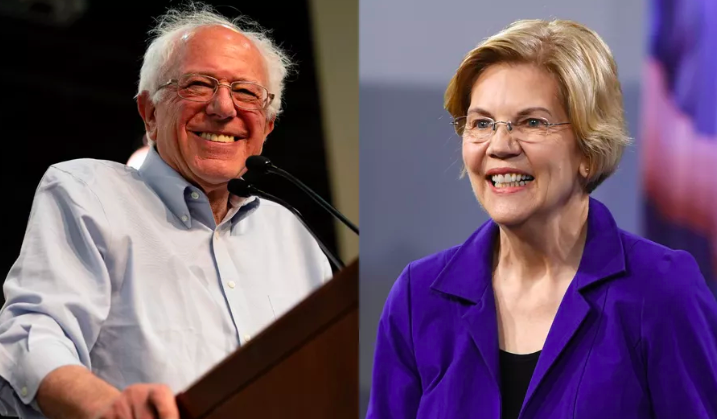

Exit question: With this example comes expectations. Perhaps Bernie Sanders and Liz Warren will be the top-two finishers in New Hampshire, but right now neither is even competitive with Joe Biden in the polls. Does finishing out of the top two mean their candidacy is finished as well?

No New England candidate in the modern era has ever lost New Hampshire and then gone on to become their party’s nominee.