President Joe Biden wants to spend $109 billion on free community college for all. What could go wrong?

If the college is the University of New Mexico at Los Alamos, or San Bernadino Valley College, quite a lot.

Those two schools ranked at the bottom of a recent analysis of community colleges by Wallethub, thanks in large part to dismal graduation rates. At UNM-Los Alamos, just 19 percent of students graduate from their two-year program within three years. At SBVC (“Go Wolverines!”), it’s 18 percent.

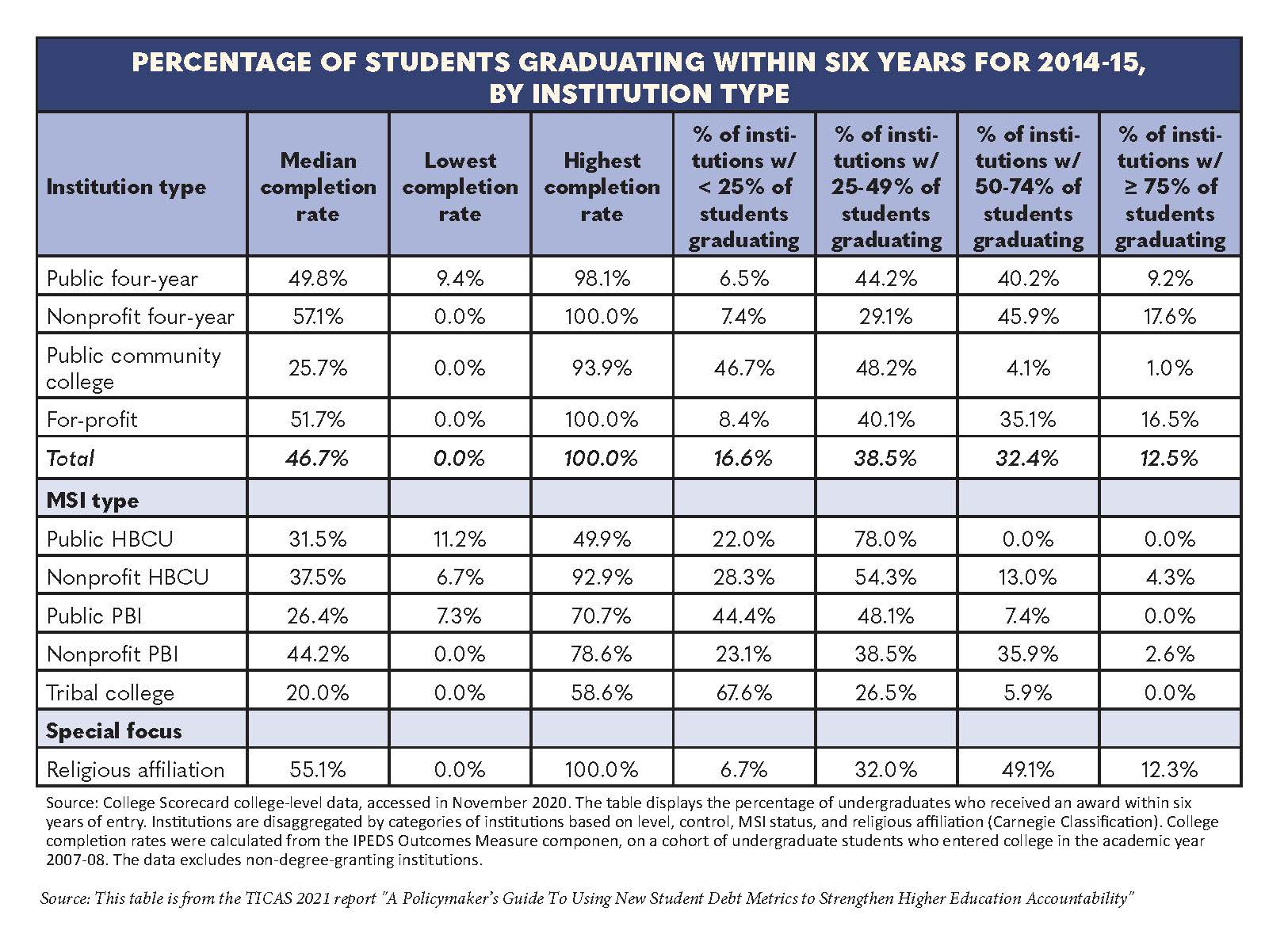

Those numbers are disappointing. Unfortunately, in America’s community college system they’re all too typical. According to data from The Institute for College Access and Success (TICAS), the median completion rate for community college — students getting their degree or certificate within six years of enrollment — is just 25.7 percent.

That’s half the rate of four-year state universities (49.8 percent) and “for-profit” or career colleges (51.7 percent).

Which is why some are raising questions about Biden’s proposal to spend $109 billion on “free community college.” It’s part of the $3.5 trillion spending plan recently advanced by House Democrats and expected to pass on a straight partisan vote in the budget reconciliation process.

“Before the feds invest this money in community colleges, we need to change the mindset,” says Ray Domanico, senior fellow and director of education policy at the Manhattan Institute. “We need to change the incentives. Right now, the schools get the revenue regardless of the outcomes.”

Part of changing that mindset is recognizing the needs of a changing society.

Many students today are adults working full-time while raising a family as they look to expand their earning potential and improve their quality of life. Pouring money into failed community college programs isn’t going to help them, or local employers in need of a skilled labor pool. Meanwhile, a myriad of alternatives beyond “traditional” four-year schools meet the reality of student needs today with flexible schedules. In fact, career schools have led the development of more nimble and innovative education options, like online learning, that have been widely adopted and accepted as the norm today.

Not all community colleges are the same, of course. Pamlico Community College in Grantsboro, N. C. has a graduation rate of around 50 percent at a moderate cost. Mitchell Technical College in Mitchell, S.D. has a graduation rate above 70 percent. They rank near the top of the 685 community colleges reviewed.

At the other end of the spectrum is #683 ranked Sisseton Wahpeton College in South Dakota. Graduation rate: 3 percent.

The math is hard to avoid. Giving billions of dollars to community colleges means subsidizing a significant amount of academic failure. As Tom Lee, a data analyst at the conservative American Action Forum puts it, “At least 60 percent, or $65 billion, of the $109 billion allocated for free community college under President Biden’s American Families Plan would go toward students who never finish or receive a degree.”

Defenders of the community college system argue measuring their performance by “completion rates” is unfair. They note the schools cater to non-traditional students, many of whom use college classes differently than typical students attending a four-year school.

“There are people who are looking to get what I call ‘new-collar jobs’ like computer coding, hospitality, things like that. And because our k-12 schools don’t teach these skills, they push it onto the community colleges,” Michael T. Miller, professor of higher education at the University of Arkansas, told InsideSources. “Other students want to get some courses out of the way before they transfer to four-year schools. So you get people who enroll in the local community college, they take two classes — like the hard chemistry class or the language classes — then transfer out. And then that community college is showing a failed student or somebody who drops out.”

Nonsense, says Dr. Jason Altmirme, president and CEO of Career Education Colleges and Universities (CECU) and a former Democratic member of Congress.

“Completion rates are completion rates. If you’re an education policymaker, the facts are what they are. And the facts are our sector’s graduation rates are double those of community colleges.”

Altimire notes the Biden administration’s education policy, like the Obama administration, is openly hostile to privately-operated career colleges and often uses completion rate data to push regulations on the industry. The source of the completion-rate data above — TICAS — was co-founded by Robert Shireman, an anti-career college activist and veteran of the Obama education department.

Shireman, a longtime advocate of free college who left the Obama administration “under an ethical cloud,” according to a watchdog organization, is now helping the Biden administration craft higher ed regulations. Critics note these regulations would favor community colleges regardless of the schools’ performance and ignore successes in the career-college sector.

“We do not support proposals that arbitrarily pick and choose winners amongst different sectors of higher education,” says Aaron Shenck, executive director of the Pennsylvania Association of Private School Administrators. “Unilateral funding proposals discriminate against students who decide to attend other institutions that often have better student outcomes than the government-subsidized alternative.”

One area where advocates for community college and career colleges agree: Serving non-traditional students skews the numbers and makes it harder to measure results. Expecting these students — many of them older, working full-time, or who struggled academically in high school — to graduate at the same rate as four-year students is unrealistic and undermines the goal of transitioning them into jobs. That is why career college advocates point to job placement as another measure of success.

“There are many professions that are served by career colleges — aviation and auto technicians, green energy with windmills and solar panels, nursing and medical assistant professions, truck driving, HVAC — all of these professions Americans see every day, and a substantial portion are produced by our sector,” Altmire said. “My question for policymakers is this: What are you going to do to get graduates from those professions to feed the pipeline of the future workforce? Where are those graduates going to come from?”

There can be lessons learned from many of the private companies, including many Fortune 500 companies partnering with schools. Their investment is a clear indicator that they value a school’s program and that it is turning out skilled and qualified graduates they see as valuable employees. FedEx, H&R Block, McDonald’s, UPS, and Target are just a few of the companies developing these partnerships with both community colleges and career colleges.

“Just throwing money at them isn’t going to solve the problem,” Domanico added.