Much of the universal reverence attached to Henry Aaron’s name is related to figures. You know, something about home runs.

Several years ago, one of his telephone numbers contained a conspicuous set of figures.

How about 7-5-5.

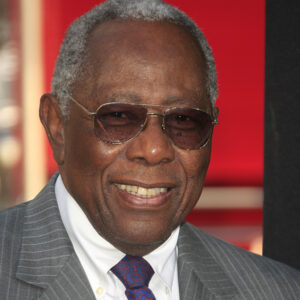

Aaron, who died on Friday at age 86, once told me, “I didn’t ask for it. The phone company just did it.”

That privilege must be reserved for icons.

Aaron, the 10th Baseball Hall of Fame player to die since last April, was a different kind of cat. Humble, unassuming, methodical, dignified. A hard hat, lunchpail-type dude. A guy with strong hands, quick wrists plus enough baseball records in the book to make Stevie Wonder take notice. And enough intestinal fortitude and resolve to stare down racial hatred and still get an A-plus grade on the home run exam.

No brag, just fact.

Some have called Aaron the most underrated superstar in any sport. Perhaps because he played in Milwaukee and Atlanta.

Imagine if he were based in New York or Los Angeles, the nation’s top two media markets. He certainly would have won more than one Most Valuable Player award.

Despite where he played, Aaron’s bopping bat was the source of much resentment because he was in hot pursuit of a superhero, Babe Ruth. Many longtime fans viewed The Babe as godlike, a Zeus in pinstripes. Some believed a Black person had no right to break his record. And if anyone deserved to surpass Ruth, it should have been a Mickey Mantle or a Ted Williams, both white players.

Note legendary broadcaster Vin Scully’s astute call that Monday night in 1974 when Aaron went immortal with historic No. 715: “A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.”

And let’s be real because numbers and figures don’t tell the entire story: Before we ever heard of this Black Lives Matter phenomenon of today, there was the Hank Aaron Social Justice Movement.

This movement was about protecting Aaron from the threats of vicious racists using hate mail to intimidate. How would you feel after being incessantly bombarded with the n-word and animal references, such as monkey and gorilla, threats of being shot between the eyes (just read Lonnie Wheeler’s book, “I Had a Hammer.”)

The death threats against Aaron were so vile that he was assigned a personal bodyguard, Calvin Wardlaw, a plainclothes policeman who shadowed Aaron, particularly at home games. Wardlaw once told me, “It was mindboggling that people would want to harm him. I always had my binocular case with me. I had my snub-nosed .38 and my badge in my case. He (Aaron) picked up from me that you never sit with your back to a door.

“It was quite an experience. There were no incidents, thank God. It worked out.”

And thank God, there was no Twitter, Instagram, TikTok or Facebook back in the day. One can only imagine if there were .

That’s what makes Aaron so special. In the 1970s, he faced multiple pressures from multiple sources and still hit it out of the park. Did Pete Rose deal with racial animosity when chasing Ty Cobb’s all-time hits record?

Uh, don’t think so.

Time to get real again: Many baseball fans still recognize Aaron as THE legitimate all-time home-run leader. Not the alleged steroids-induced Barry Bonds (762).

And did you see what the “New York Post” editorial board – not the sports section – published the other day about Bonds: That steroids “turned his Bill Bixby frame into Lou Ferrigno.”

Aaron also wasn’t a stranger to the nation’s capital. In January 2001, President Bill Clinton bestowed him with the Presidential Citizens Medal. An award that Muhammad Ali also received that same day. Which meant White House photographers snapped various portraits of the two icons in exclusive conversation (yes, I have one).

Note that Ali once said Aaron was “the only man I idolize more than myself.”

In July of 2002, President George W. Bush honored Aaron with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian award. In May of 2004, Aaron was among an A-list of speakers and presenters at Constitution Hall here for the 50th anniversary commemoration of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, which essentially struck down legal segregation.

In addition to Aaron’s 755 home runs, there’s another mythic figure: He accumulated 3,771 total hits; if you delete ALL of his home runs, he still would own more than 3,000 career hits, a milestone alone that would loom as Hall of Fame worthy.

No flash, just bash.

Aaron also served as an elder statesman and social justice warrior for Major League Baseball, often questioning the lack of people of color managing teams and spearheading front offices.

And, from 1973 to 1996, the percentage of American-born Black players hovered in the high teens; now, the figures are in single digits.

Aaron once told me, “Baseball should try to find out why more American-born Blacks aren’t playing the game . . . Black players have played a very instrumental role in promoting this game. Jackie Robinson took more abuse than anybody in baseball; he took a lot of abuse just to play this game.

“Baseball owes something to Black people.”

Again, it’s about the figures – in more ways than one.