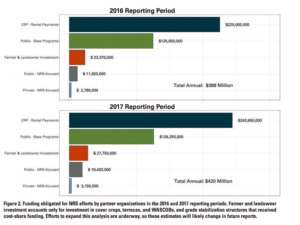

Just four years after implementing its Nutrient Reduction Strategy (NRS), Iowa’s public-private funding dollars for curtailing nitrogen and phosphorus runoff into Iowa and national waterways has reached $420 million. This is $32 million more than in 2015-2016, and nearly three times more than the first full year of data reporting in 2014-2015 (approximately $105.4 million).

The NRS is a program implemented in Iowa in 2013, as well as in 12 other states whose waterways lead into the Mississippi River and onto the Northern Gulf of Mexico. As part of the 2008 Gulf Hypoxia Action Plan establishing the Hypoxia Task Force, all 12 states who border the water body were required to assemble and implement a nutrient reduction strategy to reduce the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus draining into the gulf and creating a hypoxia zone (also known as the “dead zone” or algal blooms).

This zone is an area of the Gulf of Mexico that cannot support oceanic life due to the lack of oxygen in the water. Nitrogen and phosphorus are key nutrients needed in plant life. When algae and ocean plants absorb these nutrients, it encourages the growth of these plants and algae, which take up the area’s resources — such as oxygen — which other sea life requires, creating a hypoxic or “dead” zone. According to the Hypoxia Task Force, the zone was supposed to be reduced down to 1,900 square miles by 2015. The task force has since readjusted its goal, aiming to reduce the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus being expelled to the gulf by 45 percent total by 2035.

According to former interim-director of the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Research Center (established at Iowa State University in the NRS plan) and a developer of the plan, John Lawrence, Iowa is a heavy contributor to the hypoxic zone, expelling an average of approximately 300 million tons of nitrogen per year (as of 2015). A 45 percent reduction in nitrogen alone means eliminating 135 million tons of runoff.

The way to address these specific challenges facing the state, Lawrence said in an interview with InsideSources, is to use a voluntary, public-private, science-based approach to point and non-point pollution centers. Point pollution sources pertain to waterways that experience direct pollution from a source, such as cities and industry. Non-point sources pertain to sources that indirectly pollute waterways, predominantly farmland.

Lawrence said that because of the size of the goal and the speed at which it needs to be met, there’s “not enough public dollars” available to completely address the problem. The strategy relies on public dollars from the state of Iowa, the United States Department of Agriculture, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, as well as private dollars from farmers, and industry to implement the methods outlined in the strategy.

To measure the progress the state is making in accomplishing its particular goal, Lawrence said that in addition to measuring water quality, the NRS uses a “logic model approach.”

“Ultimately we want to see a change in the water,” Lawrence said. “But we know that will take time and because of the weather variability you may get a good reading one season and a high reading the next and back and forth depending on a variety of factors. Before we would expect to see a sustained long term reduction of nutrients in the water, we have to see a change on the land.”

Lawrence described a four-step process that relies on the success of the steps preceding each other. In order to change the results in the water, Lawrence said the there must be changes made to the land, and in order to make changes to the land, human behaviors must be changed, and in order to spur a change in human behavior, there need to be public-private inputs. InsideSources breaks down the most recent NRS report (2016-2017) to illustrate where the accomplishments of the program are in each of its steps.

Inputs

The 2016-2017 report states that $420 million in public-private dollars were spent on implementing the strategy this year, which is $32 million more than last year. The report also states that 93 percent of this funding was public dollars. In 2014-2015, one year after the program began, the funding was at approximately $105.4 million. The report notes that the majority of funding to these programs isn’t a result of the NRS, but to programs that existed before the NRS was established. A total of $7.55 million was spent this past year on NRS-related programs. Private funding for NRS related programs was reported at $3.2 million.

In addition to public money, the Iowa Department of Natural Resources (DNR) also aids in the input process as pertains to wastewater management. In 2016-2017, 105 of 151 municipalities that are mandated by the DNR have been issued new permits for their wastewater treatment facilities. Of those 105, 51 have submitted feasibility studies for technological improvements to their systems. A total of 12 cities and seven industries met NRS point source reductions targets for nitrogen removal this year at 66 percent removal. Five cities and three industries met reduction targets for phosphorus removal of 75 percent. Thirteen wastewater treatment plants have committed to construct upgrades to remove nitrogen and phosphorus.

This year, the Iowa Nutrient Research Center funded 11 projects to evaluate best practices in nutrient reduction, totaling over approximately $1.3 million, including a network of water quality sensors deployed throughout eastern Iowa. Nine projects from the center were completed this year. According to ISU’s list of evidence-backed practices, over 20 exist to reduce nitrogen and phosphorus.

Human Behavior

The NRS uses human behavior and attitudes towards the NRS as a precursor and indicator of reduction in nutrient runoff. In order to engage the human aspect of reducing the flow of nitrogen and phosphorus, the NRS uses the number of annual public outreach events as precursor to human behavior, as well as uses farmer feedback surveys to indicate how likely he or she is to incorporate reduction practices on his or her respective farmland. For the reporting years, a total of 720 events were held across the state, targeted as different age groups and in different formats (teaching, conference, field days, etc.), reaching a total of 75,671 people. Polk County received a majority of the 720 events, totaling over 64, with a majority of counties receiving between zero and six.

The results of these events are measured by surveys administered to random farmers, based on which land in a particular watershed is being measured. Before asking about specific conservation practices, the survey asks about general knowledge of the NRS. In 2015, at least 69 percent of those surveyed had some knowledge about the NRS. In 2017, that percentage is 77. On more direct questions seeking the views on statements such as “I would like to improve conservation practices on the land I farm to help meet the Nutrient Reduction Strategy’s goals,” “I am concerned about agriculture’s impacts on water quality,” and “The nutrient management practices I use are sufficient to prevent loss of nutrients into waterways,” the survey shows no statistical change over time in the responses. The report specifically states, “analysis of covariance for these questions found no statistical differences between each year’s responses, suggesting that, as measured by selected statements, there has been effectively no change in attitudes toward the NRS among farmers in the Iowa HUC6 (HUC6 is a particular watershed being surveyed this year).”

Land

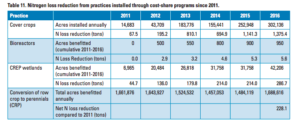

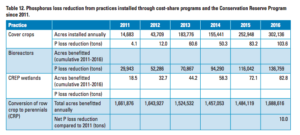

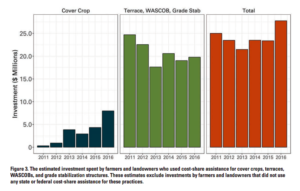

Iowa’s total land area is approximately 35.7 million acres, with 33 million used for farming. An average of 26.6 million acres is dedicated to corn and soybean row plants, which are the main sources of non-point source contamination. With the help of the Nutrient Research Center, the strategy has been able to promote several strategies to reduce nitrogen and phosphorus runoff including: cover crops, tillage, and in-field fertilizer management. These practices have lower nutrient reduction potential, as compared to what the strategy calls edge-of-field practices, as well as lower start up costs, but must be done annually to continue reduction trajectories. Edge-of-field practices include building terraces (layered crop land) and bioreactors, and have higher upstart costs, though are more effective in reducing runoff for the life of the structure. There is also the method of field retirement which is found to be the most effective but costs the most money, as well as switching from an annual crop to a perennial crop.

In fall 2016, a total of 300,000 acres of cover crops were planted through cost-share funding, which is up from 260,000 in 2015. The report states that this does not account for the total acres of cover crops planted in Iowa without cost-share funding. The report suggests that at least 600,000 acres of cover crops were planted in fall 2016. Lawrence said that the strategy is constantly improving, citing that this reporting year was the first year that farmers could get crop insurance premium reductions if they planted cover crops. Lawrence also said that there is a public-private pilot program in the works that conducts in-field surveys on fertilizer application and the use of cover crops to get more accurate data.

According to the report, however, in order to make a larger impact on the 45 percent reduction, the amount of acres that need to have cover crops on them needs to be between 10-14 million, which would require additional external funding.

Water

As the last step in the logic model approach, the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus in the water is critical in measuring reduction efforts, but also presents the most challenges in accurately measuring reduction. Lawrence said that measuring water quality presents a challenge, as different watersheds behave differently when it comes to drainage, and that the weather of a particular month can drastically impact results. According to the report, a total of 88 percent of Iowa’s land drainage is measured with sensors, leaving a 12 percent gap in land.

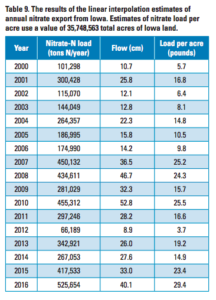

According to the report, nitrate (nitrogen) export in 2016 was approximately 525 million tons, at 29.4 pounds per acre. Over the last four years, the amount of nitrate that has been exported from Iowa is approximately 342 million tons, 267 million tons, and 417 million tons, respectively. It is the first time that the tonnage has reached 500 million since the data had been collected in the year 2000.

As for phosphorus, finding an accurate, yearly measurement is more challenging. According to the report, “the data sets indicate that the monthly frequency of monitoring at fixed station sites is not sufficient to estimate phosphorus loads because the amount of phosphorus in rivers and streams changes very rapidly with changes in stream flow. It is unlikely that phosphorus load estimates can be obtained without event-based sampling or continuous monitoring.” According to the report, a method to overcome such challenge is currently in development.

Going forward

Lawrence said that the only way to reduce the amount of nitrates in the water is by changing behaviors, and thus requires more inputs overtime, which requires more public dollars. In 2016, the state received $9 million from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to support water quality demonstration projects. A total of $3.8 million was made available statewide for in-field management practices. Lawrence said that since 2013, public funding on an Iowa level has remained “flat or minor,” and said that the initiative needs more dollars to be successful.

The current farm bill is set to expire in 2018 and the Trump administration has proposed cuts to USDA spending, as well as cuts to agricultural research. While nothing is certain yet about the bill, a water quality funding bill in the Iowa Legislature, Senate File 512, aims to increase funding for water quality by establishing a $15 million water quality infrastructure fund. Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds has called on the bill to be one of the first she signs into law in the new legislative session.