Buried in the $2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) is a big restriction on business on page 524 of the 880-page document. It’s so far gotten little attention — except perhaps from its beneficiaries — labor unions.

This section says that to qualify for a loan or loan guarantee from the Treasury Department, a business must “remain neutral in any union organizing effort for the term of the loan.”

“Remain neutral” may sound innocuous, like assuring the status quo at a company will be preserved. But in the context of labor organizing, it is a kind of gentlemen’s agreement with union organizers to not interfere. It means that a company’s management may not respond to a union’s bid to represent its workers.

To get a loan and survive this unprecedented pandemic crisis, a business may have to sign away the right to raise even then slightest objection to being unionized. You may even be obligated to roll out the red carpet.

Unfortunately, the CARES Act does not specify what remaining neutral would require when it comes retaining a federal loan. Unions need only lodge complaints of unfair labor practices to potentially endanger a company’s loan.

The act also doesn’t say who would enforce this provision. If a union were to allege a company wasn’t being neutral, how much would that jeopardize a borrower, and who would decide? The Treasury Department providing the loans or the Labor Department, which has expertise?

Larger companies could afford to lawyer up, but small- to-medium-size ones with 500 to 10,000 employees — the ones available for loans under the act — may not. Would a smaller business want to risk endangering that lifeline loan?

Other crucial questions remain unanswered. Does neutrality mean allowing union organizers on company property to talk to workers, a feature of some neutrality agreements? Would management have to turn over employee contact information, including private phone numbers, upon union request?

And on the main question of unionization itself, if a union presents a stack of cards it claims a majority of workers signed indicating they want union representation, are the managers obliged to accept the union’s claim, no questions asked?

The latter example involves how most unions officially try to get recognition under the National Labor Relations Act. Normally, companies can either accept the union’s claim or ask the federal government to conduct a secret ballot election to verify that the workers want collective bargaining. In fact, it is the only way that individual workers actually get to vote on the matter.

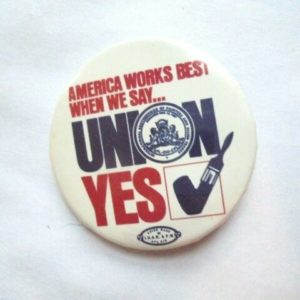

Unions have been trying for years to get Congress to pass “card check” legislation to strip employers of the right to call for an election. That’s a change in the law that will grease the wheels in favor of unions and impact many workers for years to come. It deserves serious debate in Congress.

But now the CARES Act’s “remain neutral” language may mean that unions finally get a version of card check, after all.