The author of “American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant” and “A. Lincoln: A Biography,” Ronald White has written award-winning biographies of two of America’s most consequential presidents. In an interview for “Listening to Leaders,” a new George W. Bush Institute book, White reports how presidents Lincoln and Grant listened to others, learned from their defeats, and balanced principle with pragmatism. Below is an excerpt from his conversation with Bush Institute Editorial Director William McKenzie:

Question: You have noted that Abraham Lincoln’s time as a lawyer was formative to his success as a leader. How so?

White: Lincoln’s role as a lawyer helped him understand human relationships. He told people not to get involved in litigation. He thought the nominal winner is really not a winner. He became a mediator so he could bring people together.

Abraham Lincoln was a great war president and taught himself how to be commander in chief. I think he was looking forward to the second four years where he could be a peacemaker. The basis of being a peacemaker was as much his experience as a lawyer as a politician.

Q: How did his defeats form him?

White: Lincoln had to learn what it meant to be humble. The young Lincoln could often use sarcasm to hurt. He had to grow beyond that to become the magnanimous leader we think of when he says: “With malice toward none, with charity for all.”

He also learned from being a lawyer that he had to understand the point of view of his opponents. He wanted to speak to people who didn’t agree with him. As a lawyer, he learned to understand his antagonist. But also he learned this from his defeats in politics.

Q: You have written that staying informed about public opinion helped make Lincoln a transformational leader. To what extent must a leader pay attention to public opinion?

White: Lincoln had open hours several days a week. He wanted to listen not only to leaders, politicians and generals, but to common people. He wanted to understand. He went to Gettysburg early, I believe, because he wanted to listen to people. Before he gave his address, he wanted to meet with widows and family members. He didn’t do it to shift his principles or ideals. He did it because he was a good listener.

We rightly magnify people who are great speakers, and Lincoln was our greatest speaker. But we often undersell being a great listener. Do we really listen to people? Lincoln was a great listener.

Q: Lincoln changed course when facts or circumstances changed. How did he balance principle and pragmatism?

White: The issue of slavery is a great example. He came to believe there was no possibility of “a new birth of freedom” unless that freedom was for all Americans. The question was, what and when was he going to do something about slavery? Senator Charles Sumner accused him one day of not doing enough to free the slaves. He told the senator, “You and I have exactly the same idea, but we are operating on a different clock.”

Leaders need to know the right time to put their ideals in place.

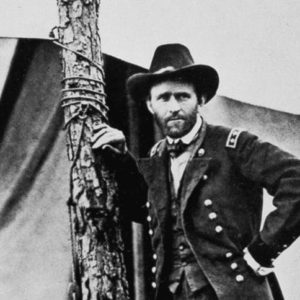

Q: What comes through in “American Ulysses” is that President Grant was a modest person with strong convictions. How hard is it to be a quiet leader?

White: We think today that leaders need to be — or simply are — extroverts. I believe Grant was an introvert. Introverts are often better listeners than extroverts. And Grant was a great listener. He would convene a Cabinet meeting, or a meeting of his generals, and listen. At the end, he would offer his own opinion or decision.

It is possible to be a quiet leader. It is more difficult in our day. But sometimes the more quiet the leader, the more thoughtful the leader.

Q: Grant pressed hard for the rights of blacks during Reconstruction and for fair treatment of Native Americans. How do effective leaders balance their moral courage with the understanding that they only have so much political capital?

White: The moral capital often goes down in the second term. Enemies begin to arise. There may be a loss of energy.

But Grant did some remarkable things in his second term. Yes, he was caught up in scandals, and we need to understand that. But he stepped forward to take on the Ku Klux Klan, using whatever power was available to him, despite the fact that he was being called a military despot.

The real leader has to not be overcome by this moral capital argument but should try to do what is right, whatever the consequences or criticisms. Grant did not bend to criticism.

Reprinted by permission of Rowman and Littlefield from Listening to Leaders: Values, Empathy, Humility, and Relationships. Edited by William McKenzie (copyright 2019).