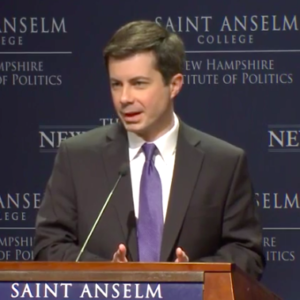

When Mayor Pete Buttigieg spoke to the crowd at the Politics and Eggs breakfast in New Hampshire on Friday, it was a laid-back, low-key affair. The quiet, 37-year-old Hoosier would have fit in well as a member of the audience at the event, held at a Catholic college (St. Anselm) and organized by the business-oriented New England Council.

“A millennial Midwestern mayor might have something different to offer,” Buttigieg suggested. And boy, did he.

Buttigieg had previously announced his support for Medicare for All (as part of a path to single-payer, or socialized, medicine) and the Green New Deal (“it’s the right beginning”). But in New Hampshire, he also mentioned in passing that he wants to eliminate the Electoral College and create a 15-member Supreme Court.

Buttigieg, who has previously said “the Electoral College needs to go,” told the New Hampshire crowd, “We’ve tolerated a system in which in my short lifetime, at my tender age, the Electoral College has overruled the American people. Not once, but twice. And we want to say that we’re a democratic country.”

On the Supreme Court, Buttigieg said he’s leaning toward a plan “where you have 15 justices: five appointed by Democratic presidents, five by Republicans, and then the other five can only be seated… by unanimous consent of the other ten. So it just takes the politics out of it a little bit, because we can’t go on like this where every time there’s a vacancy, there’s these games being played and then an apocalyptic ideological battle over who the appointees are.”

Eliminating the Electoral College and packing the Supreme Court are two big-ticket ideas. Both would require re-writing the U.S. Constitution and would result in a radical change in how America governs itself. And yet Buttigieg presented them as casually as if he were proposing a minor amendment in the tax code. And, just as noteworthy, the crowd barely reacted.

Even more interesting is the fact that Mayor Buttigieg is widely viewed as a moderate. And with Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren in the race, perhaps he is.

In Sen. Sanders’ announcement speech, he called for free tuition at public colleges, legalizing marijuana, ending cash bail across the entire country and limiting the sale and distribution of guns. And Democrats shrugged.

Sen. Warren’s taxpayer-funded child care proposal alone would cost an estimated $70 billion. To pay for it, she’s proposing something we’ve never had in the United States, a federal personal property tax: The government would take up to three percent of the wealth of the ultra-rich. Not their income for the year (which Warren would tax at 70 percent), but the home they own, the art they collect, the stocks in their retirement funds, the money saved in the bank.

Warren’s approach might be right. It might be wrong. But there’s no debate over the fact that it is a radical proposal in American politics. And yet, it’s now part of the mainstream conversation in the 2020 Democratic campaign.

Democrats claim that calling these proposals radical is just a way for opponents to marginalize them. They also claim these proposals are popular. For example, Christopher Ingraham at the Washington Post wrote a piece last month headlined “Over 60 percent of voters — including half of Republicans — support Elizabeth Warren’s wealth tax.”

However, the actual poll question was about “a tax plan recently proposed by Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) that would increase taxes on Americans with a net worth of $50 million or more.” That’s very different from the personal property tax Warren wants.

And then there’s the issue of reparations which is not only viewed as part of the political fringe but is also wildly unpopular among voters. For Democrats, the debate isn’t whether or not to support reparations as much as it is whether to extend them to Native Americans as Sen. Warren has suggested.

From the Green New Deal to decriminalizing prostitution, Democrats are laying out an aggressively progressive agenda. In the process, they’re embracing ideas that few Americans have fully debated. Eliminating the Electoral College, for example, may sound a lot better to liberals in California or New York than in Rhode Island and Vermont.

The casual radicalism of the 2020 candidates could spark the energy and enthusiasm Democrats need to defeat Trump. Or it could trap them in difficult debates far afield from the more boring issues of jobs, the economy and health care that tend to decide America’s elections.