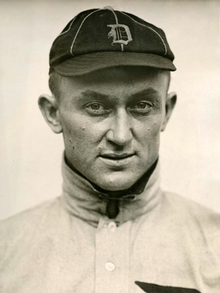

When he was 68 in 1955, retired baseball Hall of Famer Ty Cobb expressed opposition to ever being the subject of a book or a movie. The most hated huge star of the diamond before the age of steroids, he partly relented soon after, on a book. It would appear in 1961, after his death. Although he never sanctioned a movie, his acceptance of sportswriter Al Stump as his co-author would play a big role in the one movie about him. It premiered 25 years ago.

For the script, director Ron Shelton relied heavily on Stump. In contrast to his prior upbeat sports movies “Bull Durham” and “White Men Can’t Jump,” “Cobb” was decidedly negative. It featured Stump’s insights on Cobb over the final 13 months of Cobb’s life, spanning 1960 and 1961.

The 1961 book had been largely innocuous, as far as presenting Cobb in a negative light. But months after its release, Stump wrote a scathing article, “Ty Cobb’s Wild, 10-Month Fight to Live.” It featured Cobb in unflattering behaviors that Stump had allegedly witnessed. Like the movie, the article did not necessarily make it clear which took place while drunk to relieve great pain, or while merely in pain.

The film, which starred Tommy Lee Jones, made its debut 25 years ago on December 2. It had a brief run in theaters before being released on home video. Stump himself would live less than a year after its release.

The movie “tells us much about the last year of this forbidding man who was raspy and snarling and seemingly demented,” Don Freeman wrote in the San Diego Union-Tribune after seeing it. “Given a splendid performance by Tommy Lee Jones, we see Ty Cobb as he was: perhaps the strangest and least endearing of our sports idols.”

More recently, in declaring it the 50th-greatest sports movie, Vulture.com commented, “When someone gets rhapsodic about the way baseball used to be, be sure to show that person this toxic brew.”

Back in 1955, Cobb had expressed his opposition to both a book and movie, to sportswriter John D. McCallum. McCallum’s “The Tiger Wore Spikes: An Informal Biography of Ty Cobb,” published by A.S. Barnes, would appear in 1956. Cobb cooperated for a time, before cutting off access and raising the possibility of a lawsuit. Also in that letter, Cobb expressed firmer opposition to ever being the subject of a movie. He wrote, “The first thing they would want — the person playing my part — would be to jump just as hard as he could with spikes in some baseman’s face.”

He was not far off.

A minute into the 1994 movie, the following occurred. Cobb collided with a first baseman. When Cobb then dashed for second base, the announcer declared, “Infielders and catchers often bled from his spikes.”

Whether he spiked more than a few players on purpose, and not accidentally, is unproven. However, “Cobb” is on solid ground in presenting him as having filed his spikes openly as a matter of course. For that latter claim, there is a bunch of recollections from primary sources.

Some of the negative detail that Stump is the original and only source for has been discredited, by various researchers and authors. That includes, as the movie has Cobb stating, that he once killed a man. However, there is independent support for some of the movie’s negative characterizations, such as acting up in a Nevada casino.

In addition, it is true, as the movie recalls, that Cobb encountered negative feelings among fellow former players at a reunion. However, reporting shows Cobb making a generous adjustment toward those players. The setting was an old-timers’ day weekend at Yankee Stadium in 1947.

It is generally true, as the movie notes, that Cobb was jealous of Babe Ruth. Cobb had taken pride in being the top vote getter — Ruth came in second — in the first election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1936. Cobb’s feats included being the all-time hits leader, a record that Pete Rose broke in 1985. (Rose’s approaching feat led the Los Angeles Times to reprint Stump’s 1961 article.) Playing largely in baseball’s “deadball” era, Cobb had been an exponent of the little things that win games. He retired in 1928 second in stolen bases.

On the positive side and not in the movie but in Stump’s 1961 article, Cobb was charitable in his final two decades.

Stump, in addition to the 1961 article, wrote a 1994 book. Its cover title was “Cobb: The Life and Times of the Meanest Man Who Ever Played Baseball: A Biography.”

But “mean” was an accurate descriptor. Al Schacht, an American League contemporary of Cobb who also became a famous clown on the diamond, told the Associated Press in 1955, “Love him? I hated him the way everybody else in the game did. Cobb was the meanest man who ever wore a uniform. But that has nothing to do with the fact he was so much the greatest player who ever lived it’s not even close.”

Even Cobb’s daughter Shirley joined in. When future Cobb biographer Don Rhodes used the term “Jekyll & Hyde” in her presence, she liked it and replied, “How could he have been so sweet to other people and not to his own family?”

A lesson of “Cobb” is that fact-based movies can inaccurately balance out a person’s positives and negatives. Even seemingly plain facts may be discarded. For example, the movie presents Stump and Cobb as not being acquainted with each other prior to 1960. But for a lengthy feature in 1955 in the Elks Magazine, Stump both spoke with Cobb and employed a perspective that Cobb had likely relished. For example, “It’s no wonder that Ty Cobb recently exploded to this writer, ‘They used to say pitching was 75 percent of the game. Well, I’d call it 25 percent! Baseball’s lost all its science and gone fence-ball crazy!”’