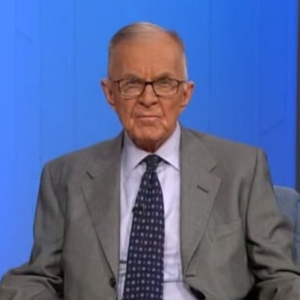

Thirty-four years ago, a former Jesuit priest threw an incendiary device into the world of televised political talk shows. He was John McLaughlin, host of “The McLaughlin Group,” who has died at the age of 89.

Until McLaughlin exploded on the scene, it was all rather sedate. The dominant programs were PBS’s “Washington Week in Review” and “Agronsky & Company,” hosted by veteran broadcaster Martin Agronsky.

In these programs, the host was magisterial and the guests were journalists who answered questions either about what they were covering or what they thought; and their answers were expected to conform to a level of decorum. “Agronsky & Company” — largely because of Agronsky’s own strong personality — had a little more flash than “Washington Week in Review,” but there was a level of earnestness about both programs.

Along came McLaughlin, who was not so much a seeker of wisdom and truth as a man in pursuit of fun and something watchable. With “The McLaughlin Group,” a window was opened and fresh air gushed in. The conventions were trounced. Shouting and loud dispute on television arrived, all skillfully goaded by McLaughlin.

The program became essential viewing not only for political junkies but also for much of the nation. At one time, it was carried on nearly 400 PBS stations, although it originated on commercial television in Washington. It was sponsored by the Edison Electric Institute.

It was also commercially successful, so it was able to pay its contributors and to have a large staff — a very large staff for a half-hour show. McLaughlin was not easy to work for, staffers who later worked with me said. Washington television circles are replete with stories of him sending staffers on personal errands and, in one case, ordering a woman to make toast for him.

All I can say is that in our very occasional meetings, he was very encouraging about my own television and radio talk show, “White House Chronicle.”

McLaughlin left nothing to chance: the effect had to be right. So shows were packaged, reworked and second and third takes were common. There was perfectionism in the riot.

He was the ringmaster, demanding terse answers, switching subjects and making declarative statements. After a “lightning round” of questions, he would opine, “The answer is.”

McLaughlin had the best opinion journalists of the time on his program, including Jack Germond, Robert Novak, Morton Kondracke, Pat Buchanan, Eleanor Clift and Michael Barone. There were falling outs with some of his stars: Novak is reported to have stormed off the set, and Germond also quit with harsh words.

But there were loyalists and people who loved McLaughlin. They include Clift and Buchanan, whose friendship with McLaughlin dated back to the Nixon White House.

In the past decade, the program fell victim to the “new journalism” it had created. As the cable networks grew, they adopted the aggressive approach to political discussion that McLaughlin had introduced, but often without the finesse or the self-deprecation, which was part of McLaughlin as a broadcaster and as a man.

He loved Dana Carvey’s skewering of the program on “Saturday Night Live.” He would openly joke about a very prudish article of advice to girls about sex that he had written when he was in the priesthood.

McLaughlin, an extraordinary man with an extraordinary legacy, was an ordained Jesuit who left the priesthood and married twice. He ran unsuccessfully as a Republican for the Senate from Rhode Island, became a speechwriter for President Nixon, and editor and columnist for National Review and then, without a background in television, reinvented political talk shows.

If you are tired of journalists shooting off their mouths and shouting at each other 24/7, blame John McLaughlin. He would have loved you for it.