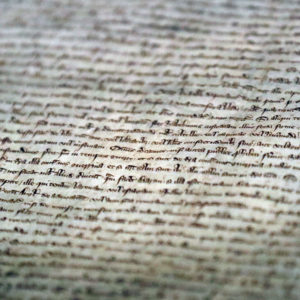

As we near America’s July birthday, it is useful to remind ourselves that preceding that date in both calendar months and centuries is the June anniversary of the signing of England’s Magna Carta. Comparing and contrasting the Declaration of Independence, which was signed on July 4 in Philadelphia, with the Magna Carta, which was signed on June 15 in a meadow at Runnymede in the south of England, has always been a useful exercise in civic education.

At first glance, most Americans would probably think it’s an apples-to-oranges comparison. While the Declaration speaks of human equality and the natural and universal rights of men, the Magna Carta is an agreement between England’s lords and a monarch, with nary a word about the broader “rights” of the everyday English subject.

And while the Declaration appeals to the “laws of nature and nature’s God,” and “self-evident truths,” to break from British rule, the Magna Carta intends to restore the traditional privileges enjoyed by the barony and Church, while acceding to the monarchy as source of law simultaneously.

In short, the Declaration is a revolutionary document in not only announcing the revolt from London but doing so on the basis of the unprecedented claim of natural rights — not divine ordinance or British customary liberties; in contrast, the Magna Carta looks back in time for the grounds of its pledges and presumes those ancient ways are the just and reasonable.

Nevertheless, the two documents are linked by the fact that they share a similar and immediate practical goal: ending (in the one case) or curtailing (in the other case) what they believed to be the arbitrary rule of a governing monarch. It’s no surprise that the colonists of North America were often quick to cite the precedent of the Magna Carta when discussing and debating their own complaints with London.

In particular, the Magna Carta offered up the concept that rule could be made safe by substituting “absolute rule” with rule through and under law. Rather than the governed being subject to the arbitrary will of whoever or whatever was the government, the Magna Carta forced government to work through the processes of the courts when it wanted to engage in a binding adjudication. It did this through introducing the concept that we call the “due process of law.” Article 39 of the Magna Carta declared that no man could be imprisoned or dispossessed “except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.” The concept was developed in subsequent centuries.

This history directly informs the concept of due process of law that is enshrined in the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. While today we commonly assume that due process refers to a set of standards for the courts, it more fundamentally bars binding adjudication outside the courts. Hence its specific language does not actually invoke the courtroom, but more generally declares “No person shall … be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

In the earliest surviving academic commentary on the Bill of Rights, Virginia judge St. George Tucker noted that the Fifth Amendment’s due-process clause meant that “due process of law must then be had before a judicial court, or a judicial magistrate.” All of government, therefore, is limited by the Fifth Amendment, including Congress and the executive. In some fundamental respects, then, the Magna Carta provides the very principle that undergirds the notion of the rule of law within the Constitution.

Although the gap in time between the Magna Carta and our own constitutional history spans several hundred years, the gap in time between the drafting and subsequent ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1787-88 and today now spans centuries as well. Just as English citizens and jurists long looked upon the Magna Carta as a constitutional precedent whose underlying wisdom was worth understanding, appreciating and, when need be, applying to new circumstances, so too one would hope that Americans would view the Constitution and its underlying principles as worthy of the kind of respect given to something not just old but also valuable for its guidance in governance.

But for that to remain the case the logic and wisdom undergirding the U.S. Constitution must be taught and retaught to each generation. Depending on the age and on tradition to uphold our attachment to our governing document is a thin reed indeed given democracies’ tendencies to look continually to the present for its ruling norms. Inertia won’t do and it is beginning to show in polls and studies of American civic attitudes.

The Magna Carta, the Declaration of Independence, and the U.S. Constitution are unique documents. But celebrating the anniversary of one should lead us back to understanding why they are memorable. The ties they share, rather than their many differences, are keys to the creation of a civilization in liberty in both the island of England and on the shores of North America.