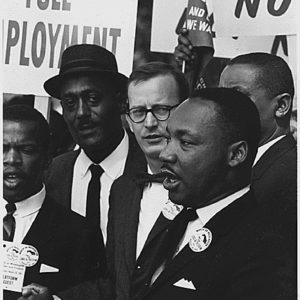

Fifty years ago, our nation’s capital was in flames. Outrage over the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. erupted in a wave of rioting that left neighborhoods across Washington so damaged they wouldn’t recover for decades.

Despite their grief, King’s allies continued to press forward with a major initiative he’d helped launch — a Poor People’s Campaign. Their goal: to build a multi-racial movement, led by poor people, to fight the poverty and racism that plagued the nation as well as the militarism that had led to a deadly war in Vietnam.

They organized caravans from across the country to converge in Washington in June 1968, where they erected a shanty town on the National Mall known as “Resurrection City.” Their efforts shamed Congress into improving some federal anti-poverty programs, but the campaign wasn’t able to sustain momentum in the midst of a national struggle to recover from King’s murder.

Today, the Washington neighborhoods that were most damaged by the 1968 unrest are home to luxury condo buildings and expensive wine bars that have left the poor behind. And the need to build a strong moral movement to tackle what King called the “evils of racism, economic exploitation and militarism” is just as critical as it was five decades ago. If you add in climate change, a growing water crisis and other environmental threats, the urgency is even greater.

Fortunately, a modern Poor People’s Campaign is reigniting that revolutionary spirit of 1968. Led by two prominent faith leaders — the Rev. Liz Theoharis and the Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II — this initiative is planning 40 days of coordinated direct action in 30 states, beginning on Mother’s Day and culminating in a mobilization in Washington on June 23.

A new report co-published by the Poor People’s Campaign and my organization, the Institute for Policy Studies, uses facts, figures and faces to make the case for the campaign while challenging some of the most prevalent myths about what’s wrong with our society.

There is an enduring narrative, for example, that if the 41 million Americans who are living below the official poverty line just acted better, worked harder, complained less and prayed more, they would be lifted up and out of their miserable conditions.

Instead, we found that the real causes — the racism, militarism and economic inequality decried by King — remain structurally ingrained at every level.

The research we surveyed shows that there’s no city in the country where the federal minimum wage can get you a two-bedroom apartment, that medical bills are the leading cause of bankruptcy, and that nearly a fifth of Americans have literally no net worth, or even negative net worth. Wages have stagnated for decades, even while the costs of health care and education have soared.

Meanwhile, systemic racism is evident in the wave of voting rights restrictions in more than 20 states; in the biased sentencing and policing practices that have expanded the share of federal and state prison inmates who are people of color from less than half in 1978 to 66 percent in 2016; and in the dramatic increase in federal spending on anti-immigrant measures, including a tenfold increase in deportations.

Finally, pervasive militarism has completely warped our sense of what’s possible to fix. Contrary to the common myth that our country can’t afford it, our report shows that the richest nation in the world has abundant resources to protect the environment and ensure dignified lives for all its people.

The problem is a matter of priorities, as more and more of our wealth flows into the pockets of a small but powerful few — and into our bloated Pentagon budget.

Since Vietnam, continuing U.S. wars have siphoned massive resources away from social needs while doing little to protect Americans. Out of every dollar in federal discretionary spending, 53 cents now goes toward the military, with just 15 cents on anti-poverty programs. Trump wants to make that gap even bigger. Under his budget proposal, 65 cents of every discretionary dollar would go to the military, and just 12 cents would go to anti-poverty programs.

Together, these crises are every bit as severe as the day King named them, and we have an escalating climate crisis to boot. But the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign showed a path for uniting people of all backgrounds to meet them.

Fifty years after King’s burial, faith and secular leaders are joining with thousands of poor people to bring it back — and to make sure he didn’t die in vain.