The prospects of the Paris Agreement becoming a reality took another big blow in Asia in July. The Philippines has decided not to ratify the Paris Agreement on Climate Change.

If the Philippines is committed to this decision, it will soon set an example for other South East Asian countries that are struggling to cope with extreme poverty levels due to slow economic progress impeded by restrictive policies like the Paris Agreement.

The Philippines depends heavily on coal to meet its energy needs. It imports 70 percent of coal from Indonesia. Recently those coal imports have been hampered by security concerns because of pirates in the Sulu Sea area. But even more than this danger to their energy security, there is a bigger roadblock to the country’s economic freedom — the Paris Agreement on Climate Change that Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte is now refusing to ratify.

The Philippines signed the Paris Agreement last year. By doing so, it had expressed its intention to contribute toward the long-term goal of the agreement (to keep the increase in global average temperature to well below 2 degrees Centigrade above pre-industrial levels, by reducing carbon-dioxide emissions) — the goal and methodology for which there is no demonstrated scientific evidence.

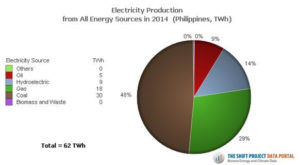

The anti-coal campaigners seldom realize the implications of a coal crackdown on the country’s economy and the livelihood of each citizen. Coal contributes 48 percent to the Philippines’ electricity production. If the Philippines were to ratify its commitment at Paris, it would have significant negative repercussions on its already fragile energy security situation.

The coal industry, being the lifeline of the country’s energy needs, has also been shown to correlate with a low incidence of poverty. Provinces with less poverty (Togon, Mankayan and Tuba) host coal mining industries. In contrast, there is no mining operations in 10 of the poorest provinces.

Recently, the newly appointed Energy Secretary Alfonso Cusi said, “Coal is the more dependable, the more reliable source for base load. … We lack capacity for dependable power. As a developing country we cannot afford not to have coal.”

The country’s finance secretary Carlos Dominguez reiterated that the government won’t close down coal plants or scale down the expansion. “There has to be an energy mix policy, but at the moment we will proceed with what we have already in the pipeline, so we will not stop everything,” he said.

But the biggest decision came from President Duterte himself. On July 18, Duterte declared that he will not honor the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. He said, “We are here, we have not reached the age of industrialization. We are on our way to it,” adding that wealthy nations were not subjected to these emission restrictions during their industrialization.

His decision was supported Cusi. “While we signed the Paris Agreement last year committing ourselves to limit our carbon emissions, we cannot ignore the fact that our level of economic development at this point does not allow us to rely completely on renewable energy sources or clean energy.”

The leadership in the Philippines has made the right decision. Rather than complying with the scientifically flawed alarmist agenda of the West, they have chosen to press ahead with their coal plants — a decision informed by the more immediate threat of a potential economic slowdown resulting from a misguided Paris Agreement that would be disastrous for people under, or barely above, the poverty line.

Other developing countries must follow their example for the sake of their impoverished people.

India and China have already expressed their reservations regarding the Paris Agreement and are unlikely to ratify it. Developing countries must prioritize economic development, and the creation of abundant, affordable, reliable energy to bring their people out of poverty — the same as Western countries did not so many years ago.