After the string of police shootings over the past year and a half, the Huffington Post reports that police departments in more than 20 American cities are now testing “less lethal” weapons. Things like pepper spray, stun guns and beanbag projectiles are all intended to cause suspects intense pain, but prevent police from having to use lethal force.

Proponents of these weapons say they will help prevent tragedies. Opponents claim that the shift from bullets to beanbags only masks a much larger issue regarding how police treat individuals in custody. But missing from this debate is recognition that widespread adoption of these technologies may create new problems — ones that may exacerbate current issues surrounding the police and create new ones.

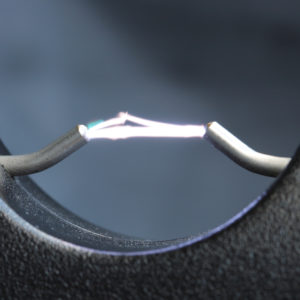

Some of the most common less-lethal weapons in police departments are Tasers and stun guns. The use of Taser technology has increased significantly. Around 500 law-enforcement agencies used Tasers in 2000. By 2013 this number had climbed to around 17,000. Though Tasers and stun guns differ in some aspects, these weapons “neutralize” a suspect by shooting varying amounts of electricity into his body. These weapons can subdue an individual without causing permanent damage.

That is, if they are used properly. Handled incorrectly these weapons can kill. The number of deaths and serious injuries from Tasers and stun-guns has prompted many individuals and organizations to demand additional training and restrictions on their use.

But there is another issue to consider when discussing these less-lethal weapons, a problem that can manifest even with proper training.

That problem is torture.

By design, these weapons leave few or no marks. While this may sound like a win-win situation for all parties involved, this feature provides not only opportunities for abuse but also built-in protection for abusers. When these weapons are operated correctly, those who oversee the police — judges, juries and superiors — have a difficult time determining if they were used properly or improperly.

In essence, the weapons can evade detection. This gives police incredible power — one that is easily abused. Stun and Taser technologies make it easy to circumvent and undermine rules that protect individuals from improper treatment.

So widespread adoption of these weapons by law enforcement is not only ill-advised; it is also downright dangerous. We’ve seen the consequences of less-lethal techniques in law enforcement before. For example, after the U.S. war in the Philippines in 1898, following the Spanish-American War, American military police imposed the “water cure” in their local precincts, torturing suspects by forcing gallons of water into their stomachs. The method typically did not result in death, but undoubtedly qualified as torture. It left no marks when “administered properly.”

After Vietnam those who participated in interrogations of the North Vietnamese brought their less-lethal techniques home. Using cattle prods and modified field telephones capable of inflicting incredible pain, the Chicago Police Department under Jon Burge infamously subjected more than 100 people to the “Vietnam Special.”

The expansion of stun and Taser use since 2000 has coincided with a sharp increase in abuse. Instead of prompting more oversight, Tasers and stun guns may actually be subjected to less. When Chicago police, for example, decided to increase its supply of Tasers from 280 to 680, use of them increased from 163 in 2008 to 683 in 2009. Instead of increasing oversight, however, the city’s Independent Police Review Authority actually relaxed its policy. While previous stun-technology use had been routinely investigated, the authority said it would no longer review all cases, stating that the volume would “overwhelm” its resources.

There is a serious problem with law enforcement in the United States. While Taser, stun and other less-lethal technologies may allow law enforcement to subdue aggressive or violent suspects without using more lethal weapons, we should be cautious before advocating the widespread use of such technologies. The same features that make these weapons appealing also make them particularly prone to abuse. As we have seen in the past, weapons that fail to leave physical marks can be used inappropriately. Sometimes, these abuses are nothing short of torture.

We should be cautious before advocating expanded use of these weapons. Moreover, the public should not accept the label of “less-lethal” as a reason to relax oversight. If we do, we might be in for a nasty shock indeed.