Shattered glass.

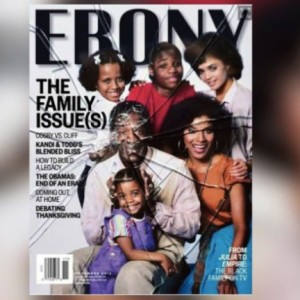

That’s the prism through which Ebony magazine views “The Cosby Show,” the hit television program from the 1980s featuring an upscale black, urban family.

The November issue of the magazine displays the show’s stars behind a broken glass pane for that fractured-family effect, with patriarch Bill Cosby at the epicenter of a cover cleverly titled “The Family Issue(s): Cosby vs. Cliff.” The immensely popular actor-comedian who portrayed Dr. Cliff Huxtable from 1984 to 1992 is surrounded by family co-stars Phylicia Rashad, Malcolm-Jamal Warner, Tempestt Bledsoe, Lisa Bonet and Keshia Knight Pulliam.

With one provocative cover, the once-iconic Ebony has catapulted itself from essentially an irrelevant enterprise back into the national consciousness. However, was Ebony kosher in its method to evoke a national conversation on the black family and the effects of the widely-publicized accusations of sexual misconduct against Cosby? A cover that has social media in a Twitter Tizzy.

Anyone not living in a cave knows by now that, depending on which media outlet you follow, somewhere between 25 and 100 women within the past year have accused the once-beloved Cosby of sex crimes, dating back to the 1960s. That’s the point: Those allegations were directed toward Cosby, not the other cast members.

So why would Ebony insert the show’s main family members on the cover with the chief target, Mr. Cosby, the man once affectionately hailed as “America’s Dad”? Remember those sentimental Jell-O Instant Pudding commercials with Cosby and the wide-eyed children.

Ebony editor-in-chief Kierna Mayo told CNN late last week, “When you understand the soul of black America and you understand how important iconography is and you understand how important the image of black family perfection … is, you realize that there’s no way to do something like this without it being hugely conversational, if not confrontational, and in many cases painful for people.”

But involving Cosby in a national conversation on the black family is one thing. Involving his fellow cast members is a whole other ballgame. Much less on the cover of a very national, very ethnic magazine.

Ebony’s cover display appears to make sacrificial lambs out of the other family members in the cast. Just for the sake of family appearance, Ebony seemed to drop them into the same black hole as Cosby, to wallow in the abyss of shame with him. How unfair. What do they have to do with Cosby’s alleged indiscretions?

Why not employ a photo of simply Bill Cosby himself? And perhaps juxtaposed with an accompanying shot of his alter-ego Cliff Huxtable. Yes, the new Ebony issue, in its entirety, focuses on black families — real and imagined — from the Obamas to the cast of the hit television show “Empire.”

Still, Cosby and his television family dominate the scene. To use an NFL analogy in the context of family, when New England Patriots tight end Aaron Hernandez was arrested in 2013 for first-degree murder, did we condemn the whole franchise?

No.

Rolling Stone magazine published a cover story in August 2013 featuring a blood-spattered illustration of Hernandez with the catchy headline “The Gangster in the Huddle.” No other Patriots players were part of the illustration. Hernandez was the bad guy in the Patriots’ family.

Cosby was the alleged bad guy in the real Cosby family, NOT the Huxtable family. We shouldn’t conflate the two.

Actor Malcolm-Jamal Warner firmly stated to “The View” co-hosts late last week, “That’s a show that we’re all very proud to have been on. And (former Cosby co-star) Keshia Pulliam said an interesting thing. Her perspective is the legacy cannot be taken away because all of the good that that show has done cannot be taken away. The generation of people of color who have chosen to go to college because of that show. You can’t take that away.”

Anyone with a heart must empathize with the other co-stars, such as Warner and Pulliam. They are being dragged by Ebony into a deep morass through no fault of their own.

“The Cosby Show” provided a brilliant piece of television history like no other programming. For the first time, we gathered in our living rooms to watch a black nuclear family living in a nice neighborhood in a major city. The father was a physician; the mother was an attorney.

For once, we saw black parents living ultra-professional lives with high-achieving, well-mannered children. Many regular black folk knew such families existed in real life before “The Cosby Show,” but they weren’t portrayed on the most powerful medium in the universe: yes, television, not the Internet.

Ten years before “The Cosby Show,” we viewed “Good Times.” Yes, it featured a traditional, nuclear black family with both parents. But that family also was accompanied by the usual black baggage of stereotypes: living in the housing projects of gang-infested South Side of Chicago, the father working two or three menial jobs just to equal one decent wage and a jive-talking son ensconced in buffoonery.

Enough of that.

“The Cosby Show” gave us the other side of the black-family theater. The aspirational side of where black folk could be through dedicated work and educational excellence. Remember, one of the constant themes in “Good Times” was how the Evans family would work and struggle and claw its way out of the ghetto.

Hey, the TV Huxtable family had already arrived in the Promised Land. They were already there, just waiting for the rest of us to join them.

Ebony cannot shatter that Huxtable pedestal with all the broken glass in the world.