In October 1947 Eric Blair, known today by his pen name George Orwell, wrote a letter to the co-owner of the Secker & Warburg publishing house. In that letter, Orwell noted that he was in the “last lap” of the rough draft of a novel, describing it as “a most dreadful mess.”

Orwell had sequestered himself on the Scottish island of Jura in order to finish the novel. He completed it the following year, having transformed his “most dreadful mess” into “1984,” one of the 20th century’s most important novels. Published in 1949, the novel turns 70 this year. The anniversary provides an opportunity to reflect on the novel’s significance and its most valuable but sometimes overlooked lesson.

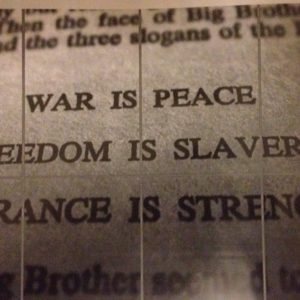

The main lesson of “1984” is not “Persistent Surveillance is Bad” or “Authoritarian Governments Are Dangerous.” These are true statements, but not the most important message. “1984” is at its core a novel about language; how it can be used by governments to subjugate and obfuscate and by citizens to resist oppression.

Orwell was a master of the English language and his legacy lives on through some of the words he created. Even those who haven’t read “1984” know some of its “Newspeak.” “1984” provides English speakers with a vocabulary to discuss surveillance, police states and authoritarianism, which includes terms such as “Big Brother,” “Thought Police,” “Unperson” and “Doublethink,” to name a few.

The authoritarian government of Orwell’s Oceania doesn’t merely severely punish dissent — it seeks to make even thinking about dissent impossible. When Inner Party member O’Brien tortures “1984’s” protagonist, Winston Smith, he holds up his hand with four fingers extended and asks Smith how many fingers he sees. When Smith replies, “Four! Four! What else can I say? Four!” O’Brien inflicts excruciating pain. After Smith finally claims to see five fingers, O’Brien emphasizes that saying “Five” is not enough; “’No, Winston, that is no use. You are lying. You still think there are four.”

Orwell’s own name inspired an adjective, “Orwellian,” which is widely used in modern political rhetoric, albeit often inappropriately. It’s usually our enemies who are acting Orwellian, and it’s a testament to Orwell’s talents that everyone seems to think “1984” is about their political opponents. The political left sees plenty of Orwellian tendencies in the White House and the criminal justice system. The political right bemoans “Thought Police” on college campuses and social media companies turning users into “Unpersons.”

But politicians can lie without being Orwellian, and a private company closing a social media account is nothing like a state murdering someone and eliminating them from history. Likewise, perceived academic conformity might be potentially stifling, but it’s hardly comparable to a conformity enforced by a police state that eliminates entire words from society.

Yet when U.S. government officials use terms such as “enhanced interrogation,” “alternative facts,” “collateral damage,” or “extremists” they understand that what they’re describing is actually “torture,” “lies,” “innocent civilian deaths” and “political dissidents.” They prefer it if others, especially the press, used and believed in Orwellian language that dehumanizes enemies of the government and makes their horrific violence sound tolerable or even justified.

We see far more nefarious and barbaric distortions of language abroad. According to reports by activists and researchers, the Chinese state has put about 1 million people including many Uyghurs — a majority-Muslim ethnic group — in “re-education” camps. Reports reveal that the camps are hardly schools. They’re brutal indoctrination sites, with inmates forced to recite Communist Party propaganda and renounce Islam.

North Korea, the country that comes closest to embodying “1984,” has hampered its citizens’ abilities to think for themselves with a disheartening measure of success. In her memoir, North Korean defector Yeonmi Park describes discovering the richness of South Korea’s vocabulary, noting “When you have more words to describe the world, you increase your ability to think complex thoughts.” It’s hardly surprising that when Park read Orwell’s classic allegorical novel “Animal Farm” she felt as if Orwell knew where she was from.

Orwell was not a prophet, but he identified a necessary feature of any successful authoritarian government. To control you effectively it can’t merely threaten death, imprisonment or torture. It’s not enough for it to ban books and religions. As long as the state doesn’t dominate your consciousness, it’s under constant risk of overthrow. We shouldn’t fear the U.S. turning into Orwell’s dystopian nightmare just yet, but at a time when political dishonesty is rampant we should remember 1984’s most important lesson: The state can occupy your mind.