What were the consequences of the longest strike of 2014?

It was the largest strike of 2014, pitting a telephone company in the declining landline business against its 1,700 workers in Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont. When the painful 18-week fight was over, both sides claimed victory. But in truth, the “victories” were costly for both sides, underscoring the limits of the labor movement in many of the aging, problem-plagued industries it calls home.

On one side was FairPoint Communications, a company asking workers for more than $700 million in concessions as it struggled back from a 2011 bankruptcy. On the other side, two tenacious unions, the Communications Workers of America and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, pushed back hard, decrying the company’s demands as excessive.

In the end, FairPoint didn’t get nearly everything it had wanted in terms of cost savings, casting doubt on the company’s ability to remain competitive. But the two unions also emerged facing a major question: does their traditionally adversarial approach to labor relations pose big risks to all parties – employees, companies and communities — in beleaguered sectors of the economy. Indeed, after having made substantial concessions to FairPoint to end the walkout, workers returned to their jobs, only to see the company cut 200 positions after announcing financial losses that it attributed to the lengthy strike.

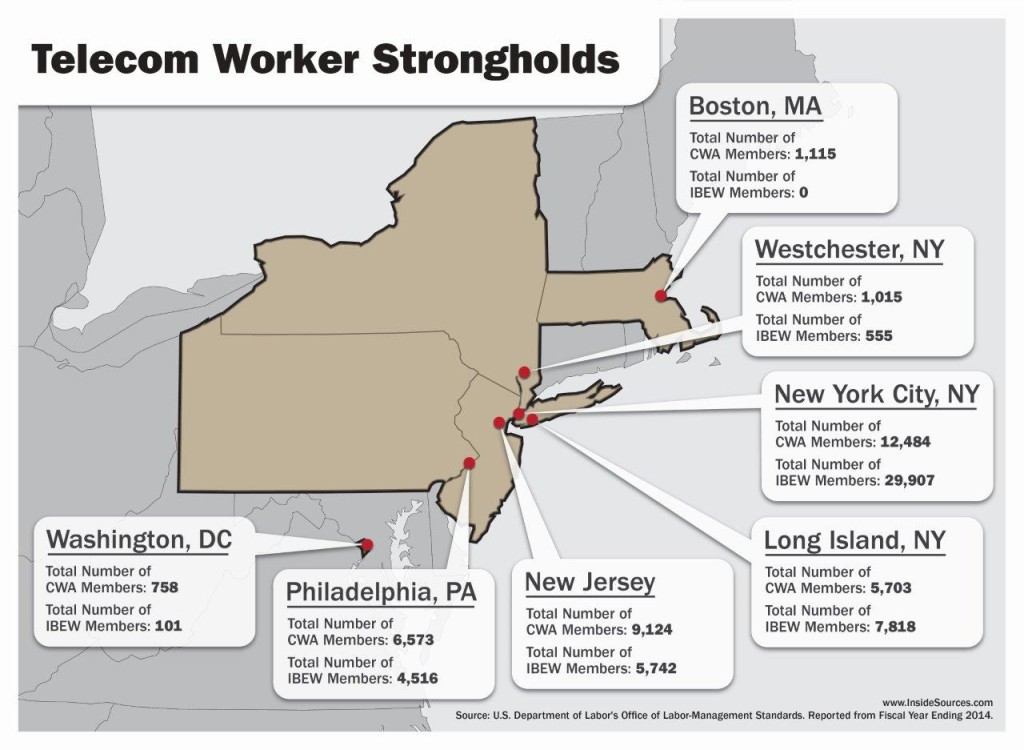

In many ways, the FairPoint saga illustrates the challenges faced by old industries, from newspapers to landline telephones, as they attempt to adapt their traditional business models to compete in the digital age. More than that, the experience of FairPoint and its unions is a cautionary tale whose lessons have resonance in the greater Boston area, the New York City metropolitan region, Northern New Jersey, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., where tens of thousands of communications and electrical workers are entering into contract negotiations with telephone companies that face less-than-bright prospects in the landline business.

Already, the unions representing these workers are staking out tough positions and hurling invective at Verizon and other companies. “The phone company never gave us a thing,” says one CWA flier circulating among members. “Once again, Verizon will test our resolve. We will have to be tougher than ever.”

In the weeks before their contracts expired last August, FairPoint’s workers were fuming at the many concessions the company was demanding, among them freezing pensions and eliminating retiree health coverage. Those demands are popular throughout Corporate America, and even the Teamsters recently informed many retirees and current members that it may have to cut pension benefits.

FairPoint also pushed for a two-tier wage plan in which new hires would earn considerably less. It also sought sweeping freedom to contract out work done by unionized employees, and it insisted on cutting the numbers of paid sick days to five per year from an unlimited amount. And with its unionized workers paying nothing out of pocket toward health insurance, FairPoint proposed that workers start contributing several thousand dollars each annually for coverage.

“We went into this knowing we had to take concessions, but the type of concessions they were asking for we absolutely weren’t going to concede on without a fight,” said Peter McLaughlin, head of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers local representing Maine telephone workers and co-chairman of the unions’ bargaining committee.

FairPoint officials saw things differently. In 2007, the company, based in Charlotte, N.C., purchased Verizon’s Maine-New-Hampshire-Vermont landlines and Internet operations — 1.6 million phone customers and 230,000 high-speed Internet customers — for $2.3 billion. But that move quickly stumbled, tripped up by recession, high borrowing costs and major problems adopting a new operating system. FairPoint filed for bankruptcy in 2009, and last summer — out of bankruptcy and its union contracts expiring — the company sought far-reaching concessions, maintaining that the contracts were extravagant relics of another era.

“The unions have dug in on almost all of their current benefits under contracts from a bygone era,” said FairPoint’s spokeswoman, Angelynne Amores Beaudry, before the strike.

But the unions and many workers maintained that FairPoint was seeking far deeper concessions than it needed to become competitive. Union officials argued that FairPoint — and the hedge funds that owned a majority of its stock — wanted to quickly slash labor costs to help sell off the company to the highest bidder, although the company insists its actions were driven by the need to stay competitive.

FairPoint faced a stark reality: it was in a declining sector. According to the most recent Census data, 71 percent of households had landlines in 2011, down from 96 percent in 1998 — the result of mobile phones’ soaring popularity. Notwithstanding this trend, FairPoint saw considerable promise, convinced it could improve profits by adding more landline customers and having customers add Internet and other broadband services.

Beyond that, many companies have adjusted to the new marketplace by introducing glass fiber wires to replace copper wires, with more than 37 million Americans making the switch. Fiber has enormous advantages over copper because it transmits data faster, needs less maintenance and requires far fewer upgrades as telecommunications technology improves. But this innovation has the potential to displace many workers whose jobs are to maintain copper networks, just as automation displaced many newspaper craft unions, like the typographers.

Faced with such realities, FairPoint was reluctant to budge from its original demands, an unusual approach that partly reflected its precarious financial position. In the end, FairPoint declared an impasse in the negotiations and imposed its many demands on the workers, a move that enraged the workers.

The two unions also adopted an unusual strategy. A year before the contracts expired, they were mobilizing for battle, hiring a consultant to help prepare and rally workers for a strike. The consultant and the unions created a Website – fairnessatfairpoint.com – and a Facebook page to spread the word. They also set up a communications tree and designated 70 “mobilizers,” each responsible for keeping 15 to 20 workers informed and mobilized.

“These unions were so forward-looking, it’s rare,” said Amy Masciola, the consultant. “They said, ‘We know we’re in for a big fight.’”

Last October, two months after the contracts expired, the two unions walked out.

Mark Cryer, director of the University of Maine’s Bureau of Labor Education, said it’s risky for workers to walk out when they are in a declining industry, like landlines.

The company was confident it could outlast the strikers, quickly employing replacement workers. But those plans were thwarted by four unusually big snowstorms, which knocked out many landlines. Soon hundreds of customers were complaining to local, state and federal officials about delays in restoring service. The unions said the replacement workers were not skilled enough or familiar enough with the terrain to fix the landlines quickly enough. Soon Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and other lawmakers were slamming FairPoint, pressing it to reach a settlement.

Meanwhile, the picket lines held strong, and for two months, the two sides waited to see who would blink first. “It seemed the parties were digging in and digging in,” said Gary Chaison, an industrial relations professor at Clark University in Worcester, Mass. “If ever there was a case where mediation was needed, this was it.”

With the strikers holding solid and with the company under huge criticism for delays in restoring storm-battered service, FairPoint agreed to mediation. Prodded by federal mediators, it moved off its original demands and reached a settlement on February 19.

The two sides compromised. There would be no pension freeze for current employees, but pensions would accrue at 50 percent of the old rate. The retiree health plan would be abolished, but for those who retired in the 30 months after the deal was reached, FairPoint would pay up to $800 a month for health reimbursement until they reached Medicare age. The company lost on two-tier wages, and it received less freedom to contract out that it had sought. But it still won some flexibility for making such hires.

The unions sought to cast the outcome as a victory, saying that they beat back the most Draconian elements of FairPoint’s initial proposal. “Considering what was imposed on us, we absolutely won this,” said Don Trementozzi, president of local 1400 of the Communications Workers of America in Maine and co-chairman of the union bargaining team.

But some union members were not so enthusiastic, “I wish I could be more positive about it, but I don’t know,” said Alan Castonguay, a FairPoint mechanic from Livermore, Maine told the Portland Press Herald. “We lost a lot.”

Tim McLean, a 20-year cable splicer for FairPoint who is an IBEW member, also voiced dismay with the company’s harsh demands and the strike’s results. “I’m not happy that we lost a lot of benefits, no, but I’ll be happy after four months just to have a paycheck again,” he said.

FairPoint, as well as Wall Street, say the company did what it had to do to position itself for survival.

“They’ve gotten a much more competitive compensation structure with the unions,” said Barry M. Sine, a Wall Street analyst with Drexel Hamilton. “They’ve reduced obligations on the balance sheet.”

What the future holds for FairPoint and its workers is unclear. But this much is apparent: if this industry has any hope of thriving once again, labor and management can hardly afford more such costly confrontations.