A few days ago a family member who takes an injectable medication discovered a problem. The specialty pharmacy that had mailed the medication neglected to ship enough needles. No problem. We’ll just pick some up at the drugstore.

Or so we thought.

When we told the pharmacist what we needed, she said that unless that pharmacy filled the prescription or we could bring the prescription in, she was legally prohibited from selling us needles. We called the specialty pharmacy several states away and were told it could ship us the needles — but they wouldn’t arrive until the next day.

My relative had no choice but to reuse a dirty needle.

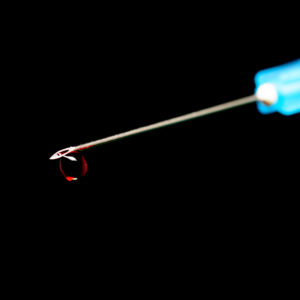

The risk of reusing needles isn’t trivial. They can become so weak with repeated use that they may break off under the skin. They also dull, meaning successive injections can be more difficult and cause pain, bleeding and bruising. Reusing needles can also cause everything from local infections to systemic blood infections.

My relative will likely be fine. We cleaned the needle with alcohol and a sterile solution, and the new needles arrived the next day. But our trouble buying needles highlights a real problem with government policy — one that’s literally killing people. The laws pertaining to the sale and possession of needles are part of the war on drugs: limiting access to needles purportedly creates an obstacle to people who want to take injectable illegal drugs like heroin.

Unfortunately, good intentions don’t always translate into good results. Rather than preventing people from injecting illegal drugs, these laws push people into using needles more than once or worse — sharing needles with other people.

Indeed, those most at risk of contracting a disease from used needles are those who use illegal drugs. This has been seen recently in rural Indiana, where a town of under 24,000 people saw an outbreak of 184 new HIV infections. Neighboring Kentucky has the highest hepatitis C infection rate in the country, largely attributed to the state’s high rate of opiate addiction.

State laws vary widely with regard to the possession and sale of needles and syringes. States like Florida, Pennsylvania and West Virginia criminalize the mere possession of these items. Others, like Kentucky, have implemented clean-needle exchange programs to reduce the spread of disease. Similar programs have achieved remarkable success. After beginning its needle-exchange program in 2008, the District of Columbia saw the average monthly rate of HIV infections drop by nearly 70 percent. HIV diagnoses related to intravenous drug use fell to an all-time low of 11 percent in Baltimore after the implementation of its exchange program.

State laws are undeniably important, but federal law remains highly problematic. Back in January, Congress effectively ended a 30-year ban on using federal funding for needle-exchange programs. Money can now be used to pay for overhead, support staff, supplies and transportation to make needles more accessible.

There’s just one catch: It’s still illegal to use any federal money to buy needles and syringes.

The problem here is obvious. Although needle-exchange programs have been shown repeatedly to be effective in combating disease transmission, some government officials refuse to give up this battle in the ever-failing drug war. Despite overwhelming evidence that easier access to clean needles reduces all sorts of problems, some governments simply refuse to change its policies.

Take, for example, the HIV cases in Scott County, Indiana. The Centers for Disease Control estimates that treating these cases will cost at least $100 million. An average needle exchange, meanwhile, costs about $100,000 to $300,000 to operate annually. These programs are also highly successful. The prevention rate for needle-exchange programs can reach upward of 80 percent.

It’s not just drug users who suffer from these poor policies. People like my relative, for instance, are forced by these policies to choose between forgoing a dose of needed medication or reusing needles. Diabetes patients, faced with frequent use and sometimes difficult access, also reuse needles and face a range of mild-to-potentially-life-threatening consequences.

Drug policy has been and continues to be a subject of contentious debate. The question of needle access, however, is one with a simple answer. If we are really interested in stopping the spread of disease and other health problems, it’s time for government to get on board with easier access.