Howard Root is part of the 1 percent. That is not in the Occupy Wall Street sense of the term, though he is the former CEO of Vascular Solutions, a medical device company that he founded 20 years ago. Instead, Root is one of a tiny percentage of people who faced down prosecution from the Department of Justice and won. Root’s story demonstrates a worrisome attitude at the Department of Justice that rewards attorneys for the settlement money they bring in, encouraging DOJ employees to bring cases to court even when there is no evidence that anyone was hurt by the behavior in question. This is the case for Root, who decided to sell his company early last year after spending $25 million and five years fighting the investigation. He stepped away rather than face the risks of running a publicly-traded medical device company.

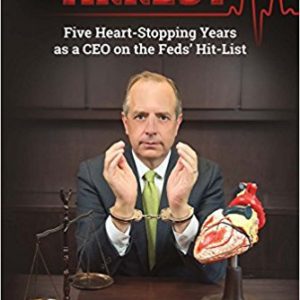

“This isn’t a cheery thing that everyone wants to read. ‘An Innocent Man’ by John Grisham is probably the closest thing,” says Root of his story, which he recounts in a self-published book, ‘Cardiac Arrest,’ released last year.

At the center of Root’s story is a product called the Vari-Lase Short Kit, which is used to treat saphenous varicose veins. During the lawsuit, the DOJ alleged that salespeople for Vascular Solutions told physicians that the device should be used to treat a different type of varicose veins. The device comprised only 0.1 percent of Vascular Solutions’ sales, was FDA approved to treat all types of varicose veins, and had never harmed a patient.

For the duration of the lawsuit, Root had Vascular Solutions pull the product from the market.

As CEO, Root had also told his salespeople only to mention the FDA-approved uses of the device. However, through an Obama-era policy called the Yates memo, which codified previously existing policy at the DOJ, prosecutors were advised to focus on the highest individual with responsibility in the organization in order to bring back settlement dollars for the department.

At their heart, these lawsuits are motivated by money. And perhaps dangerously, Department of Justice policy awards whistle blowers 25 percent of the damages recovered from prosecutions.

“One of my salespeople walked into the U.S. Attorney’s office in San Antonio, said there was this whole mass of fraud going on to the tune of $20 million so that he could get $5 million, his 25 percent share,” Root explains. “They brought him over to the prosecutors and started down that primrose path.”

“There are three motivations that I see,” says Root. “First, they have to get some kind of information to get started on these things and it is not impartial information. The money motivation on these things is someone who is disgruntled–a former employee, a current employee, a competitor, a former spouse–is going to create a story because they are going to get 25 percent of whatever the government gets.”

The Department of Justice itself is also motivated by money. Root points to DOJ publications, which boast that they have a 610 percent return on investment prosecuting healthcare fraud. In addition, within the DOJ, the amount of money won from companies is used as a marker of employee success. Awards within the department frequently come after a large conviction or settlement.

“There has never been an award in the Department of Justice for letting an innocent man go free,” says Root, who describes this as an “incredibly powerful culture.”

While Root faced criminal charges as Vascular Solutions’ CEO, the DOJ also threatened his employees. One women who worked underneath him was told that if she did not testify against Root, she would no longer be able to work in the healthcare industry. As a former nurse, this would have meant the end of a lifelong career.

Making the situation even more unconscionable is that Root and Vascular Solutions are legally barred from suing to recover their legal costs. Under the Hyde Amendment of 1997 (a different piece of legislation than the one barring federal funding for abortion), corporations with a net worth of more than $7 million and individuals with a net worth of more than $2 million are prevented from suing to recover their expenses in the event of wrongful prosecution.

“There is no way to make this a cause for the average person in America,” Root admits, “because it just doesn’t resonate. I’m a rich white male who ran a medical device company, boo hoo for me. The problem is that if it can happen to a rich white male, it can happen to anyone.”

Root instead views his success as a sign that he needs to speak out for those who cannot. Today, Root says that he is contacted regularly by others facing wrongful prosecution. They have heard of his success and are looking for advice. As much as it pains him, he says that he has to tell many of them to settle. The costs of fighting a lawsuit are simply beyond the means of most individuals and many small companies.

Even under a new administration, the effects of the lawsuit continue. After publishing his book, Root has had a number of opportunities to speak about his experience. Surprisingly, the medical device industry has been uninterested in it, but Root has had a favorable reception from criminal defense lawyers, who wanted him to speak at the American Bar Association Annual National Institute on Health Care Fraud held last May.

Originally, Root’s case was to be presented in a panel discussion with his legal representation and lawyers from the San Antonio U.S. Attorney’s Office. According to Root, the DOJ refused to participate and went as far as to say that if Root was allowed to speak in any capacity at the event, it would prevent DOJ lawyers from ever participating in the future. Without government representation, the conference would lose much of its value to professionals. As a result, Root’s invitation was regretfully rescinded.

Even with a new administration, Root remains worried about the future of the Justice Department. Sally Yates may be gone, but many of the figures who brought his case to trial remain, and the culture that pushes prosecution and settlement continues.

“It’s a lot of people who need to be changed to change the culture that is going on,” says Root, who offers to fly to Washington if the administration were to offer an invitation. So far, he is still waiting, worried that the more things change in D.C., the more they stay the same.