If a wealthy businessman paid the salary and benefits of a local police officer whose chief function was to harass the businessman’s rivals, the community would be appalled –and justifiably so. The police are the enforcement arm of the statement to keep the public safe. That’s is a lot of power. Accordingly, our system provides for standards and parameters on how that power is yielded, or at least it how it should be.

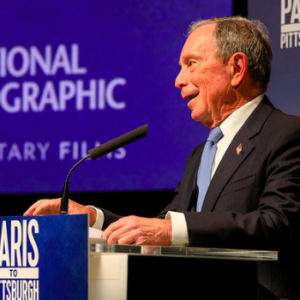

Such safeguards have been abandoned with the staffing of state Attorneys Generals’ offices in nine states and the District of Columbia with lawyers effectively paid by former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg to go after oil companies. This is equivalent to using a public office to advance individual goals. Last fall, the Wall Street Journal took a dim view of what it termed “state AGs for rent.”

In August 2017, New York University law school launched the State Energy and Environmental Impact Center with a $6 million grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. There was nothing opaque about the Center’s mission. It was to make sure state AGs had the personnel needed to pursue an activist agenda on climate change. It is now evident that in pursuing that mission, ethical lines are being crossed. The “special assistant Attorneys General” dispatched by the Bloomberg-funded program are not merely being paid for by New York University and providing legal expertise to help enforce state environmental laws. They are using a public office to sue oil companies that Bloomberg and his environmental activist allies blame for climate change and insist should pay to address its possible consequences.

This was evident fall when then-acting New York state Attorney General Barbara Underwood announced a suit against ExxonMobil alleging the company misled investors and shareholders about the impact of climate policies on the company’s long-term profits. Critics said Underwood was exceeding her statutory authority but the fact that Matthew Eisenson, on loan from the State Impact Center, was among the individual lawyers bringing the suit on New York’s behalf prompted ethical concerns. Within weeks, the Government Justice Center, a conservative watchdog organization, filed a complaint with the state’s Joint Commission on Public Ethics accusing the attorney general’s office of misconduct for enabling resources provided by private interests to set and execute public policy.

From the start, there have been contortions around the ethical legitimacy of embedding environmental activists/attorneys in state offices. Oregon’s Attorney General flagged the description of these lawyers as “volunteers” as not passing the smell test. There has also been resistance to transparency. Earlier this year a judge ruled that Virginia’s attorney general must abide by a Freedom of Information Act request to learn more about the responsibilities of an attorney from the Center. State law appears to stipulate assistant AGs must be paid with taxpayer dollars, not private organizations or individuals.

What makes the special assistant attorneys general financed by Bloomberg so unsettling is the appearance of a partisan agenda. He has given millions to Democratic candidates. The Attorneys General who have publically enlisted the help of fellows from the Center are all Democrats.

Such issues raise fundamental questions about the role of state AGs. In the narrowest sense, they enforce state laws on behalf of the people of their states. As so many political and policy questions have become nationalized in recent years, it is no surprise that some AGs have taken on high-profile so-called public interest suits, such as those against oil companies. Whether or not one thinks this kind of political activism exceeds the AG’s job description, it is hard to countenance putting lawyers paid for by for an activist billionaire in the service of that activism. Imagine if Koch Industries paid the salaries of assistant attorney generals detailed to thwart suits against the company.

Ideally, Attorneys General in other states will put a halt to this ethically tinged practice. That seems unlikely since beneficiaries and benefactor are of one mind. At the very least, the nature of the special assistant attorneys generals’ work merits close scrutiny by organizations dedicated to good government and legal ethics, along with an informed public unwilling to have billionaires call the shots in how the law enforcement power of the state is funded and deployed.