Medical ethicists are raising questions about a new aesthetic neurotoxin that is being prescribed by the same doctors who invested in its launch — a product that is now being sold without the standard consumer protection oversight.

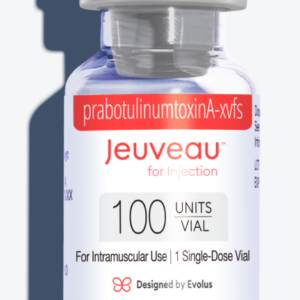

Jeuveau — sold by a company called Evolus — was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) last February, specifically to remove wrinkle lines between the eyebrows (known as glabellar or “11” lines). The FDA did not, however, approve Jeuveau for therapeutic use.

Why? Because Evolus didn’t ask. In fact, evading that FDA insight is part of the company’s marketing plan: If the drug is not designated as therapeutic, it can bypass government marketing regulations because it is not reimbursed by federal programs, such as Medicare or Medicaid.

And the investors behind Jeuveau know it. InsideSources has obtained a list of 200 physicians who were founders, principals and partners in Strathspey Crown, the company behind the new drug.

Robert E. Grant is chairman and CEO of Strathspey Crown, the corporate parent of Alphaeon, which spun off Evolus to bring the drug to market. Grant laid out his strategy in a 2013 interview — when he was still head of Alphaeon — in Pharmaceutical Executive:

“By focusing exclusively on products and services not covered by government health plans, Alphaeon is side-stepping key provisions of the False Claims Act and other regulatory strictures, and engaging physicians in ways Big Pharma cannot,” according to the article.

“We spent millions of dollars on legal research; I brought in the top healthcare compliance law firms in the country,” Grant said. “By never taking a dollar from the government, you get to operate outside of all those things.”

And while it may be true that doctors may “get to” operate outside these laws, the ethical question is “should they?”

“I can tell you flat out: If you own equity in a product that you are prescribing, you need to disclose that to potential patients,” Arthur Caplan, director of the Division of Medical Ethics in the Department of Population Health at NYU Langone Medical Center, told InsideSources. “You should also be telling them about alternatives — other neurotoxins for cosmetic purposes — and that’s just fundamental to informed consent.”

While neurotoxins like Jeuveau, Botox and Dysport are used for temporary, cosmetic treatments, they carry “black box” warnings from the FDA, the strictest and most serious forewarning the drug regulator places on medications. The Jeuveau warning states:

“The effects of all botulinum toxin products, including Jeuveau, may spread from the area of injection to produce symptoms consistent with botulinum toxin effects. These symptoms have been reported hours to weeks after injection. Swallowing and breathing difficulties can be life threatening and there have been reports of death.” [Emphasis added.]

Eric Campbell, a professor of medicine and director of research at the University of Colorado medical school’s Center for Bioethics and Humanities, agrees that Jeuveau’s business model is “something that is of concern.”

“It creates a very classic form of conflict of interest in medicine, in which the secondary interests — which in this case are financial — have the potential to influence or supersede the primary interest, which is the health and safety of the patient,” Campbell told InsideSources. “So, from that perspective it creates a classic conflict of interest.”

And then there’s the American Society of Plastic Surgeons own strict ethics code, which states that the well-being of a patient must be the primary reason for physicians to prescribe a drug — not whether they have a financial interest in promoting it.

The conflict of interest conundrum is so acute that Evolus lists it in its own Security and Exchange Commission filing as a “risk factor” for future investors: “A perception of a conflict of interest of our indirect physician investors by other physicians or consumers could negatively impact our future product sales or product approvals.”

Both Strathspey Crown and Evolus insist they are not engaged in wrongdoing and this is simply a case of doctors investing in a publicly traded company.

“It is normal and acceptable for physicians to invest in private or publicly traded companies whose products they may use,” Strathspey Crown said in a statement issued to InsideSources. “There is no requirement for any physician investor to purchase any of our products, and they freely use competitors’ products per their preference.”

Crystal Muilenberg, Evolus vice president for communications and public relations, denied that the company provides any “incentive” for physicians to use Jeuveau.

“Evolus is a public company, so anyone can purchase shares that are on the public market, and we hear from physicians across the country who tell us that they are very interested in products that bring innovations to the market, so it’s very likely that … physicians will invest in the company,” Muilenberg told InsideSources.

“We don’t disclose all the shareholders that we have, but [it is part] of a hot industry,” she said. “So there definitely are physicians that invest in companies of medical aesthetics because it is a fast-growing market — and a large market.

“There is no requirement for anyone who invested in the company, whether they were an original investor in Alphaeon, or they had started to invest in the public market, to use Jeuveau.”

In a lawsuit filed in California last year, two former Alphaeon executives claimed they were fired by the company’s board of directors for complaining about ethical issues surrounding the drug’s marketing strategy. A court spokesman told InsideSources the case has been settled.

“Between 2012 through 2017 Strathspey, Alphaeon, and Evolus widely solicited doctors and dentists to personally invest in Strathspey and Alphaeon to fund the Companies’ operations,” according to the lawsuit. “In addition to funding the operations of the Companies, doctors and dentists were told that by investing in the Companies, they would have a financial incentive to purchase medical devices and other products eventually to be sold by Strathspey, Alphaeon and Evolus.”

Only one of the many physician-investors in Jeuveau contacted by InsideSources would comment. Dr. Antony Youn, a Michigan-based plastic surgeon, said “Jeuveau is basically the newest botulinum toxin on the market … we have been using it at my practice for several months. We are still evaluating how it matches up against the other toxins.”

Asked about how his role as an investor and principal in the company affected his medical decisions, Youn said he has only prescribed Jeuveau to 5 percent of his patients, while 70 percent used Botox and 20 percent Dysport.

“I don’t get paid [to use Jeuveau] … I’m not one of their paid spokespeople, but yes I do own shares in the company that’s a parent company,” he said. “When I look at treating patients [with] a botulinum toxin, number one is what’s best for the patient.”

Caplan says that’s not good enough. “The standard is informed consent, and financial disclosure is basic to informed consent.”