Academy Award-winning actress Diane Keaton recently came to Washington and stated straightforwardly before us: “Now, at 71 years of age, Randy is in the process of dying.”

Randy is John Randolph Hall, born March 21, 1948, in Glendale, Calif. He is Keaton’s younger brother, now suffering from dementia while residing in an assisted-living facility.

Keaton landed in the nation’s capital to discuss her new book, “Brother & Sister, A Memoir,” which reverberates with candor like a ringing church bell. The book focuses on her, Randy, their lives from toddlers to adulthood and mental illness.

Before a packed audience at the 6th & I Historic Synagogue, Keaton flatly acknowledged, “I wish I could have given him more love and attention.”

The Hall family, at least outwardly, appeared to be a thriving household steeped in a blissful existence. Father was a successful civil engineer; mom was a doting housewife who maintained detailed scrapbooks chronicling her family’s lives (Keaton also has two sisters, Dorrie and Robin). Keaton and Randy, who were close siblings growing up, bonded from their bunk beds.

But on this night at the synagogue, a substantial amount of Keaton’s conversation laid bare her regrets, laments and wonderings.

Keaton was “the older, bossy sister” and Randy would, as she explained, “just tag along.”

Like when they went bottle-collecting, for instance, near a California beach when they were kids in the 1950s. They took their haul to a local A&P grocery store and redeemed them for two cents a bottle. Keaton wanted to raise enough money to purchase a jewelry box.

She writes in the book, “I have to confess I didn’t share the money I made, but, of course, Randy didn’t ask.” Which made Keaton, now 74, at the time wonder why.

Keaton’s family once lived near an airport. Randy was deathly afraid of airplanes flying over. Also, sometimes he refused to go outside; sometimes he would flash an awkward grin at inexplicable times; sometimes he spoke of ghost sightings and macabre fantasies.

And why didn’t Randy have any friends? And why did he fear the dark?

Their parents were aware of Randy’s unusual behavior as a youngster, but they didn’t seek professional help regarding his moments of mystery. Synagogue CEO and event moderator Heather Moran asked Keaton, “Do you think a factor in this was that Randy grew up at a time when mental illness was misunderstood?”

Responded Keaton, “My father just didn’t know how to deal with it.”

And it appeared that their father aimed to maintain an idyllic environment in the household, with a certain sense of order, because, as Keaton related to us: “He was the boss. We, as children, did what we had to do. My father worked hard during the day, then he came home and we all had dinner together.”

Their father also wanted Randy to play baseball and/or football, but his only son refused. “Dad wanted his son to man up,” Keaton told us.

As he became a young adult, Randy through the years was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and schizoid personality disorders, in addition to bouts with alcoholism. He’s had difficulty throughout his life maintaining steady employment and was deemed ineligible for the military draft in the 1960s.

“It was rough for him,” Keaton told us. “He lived on my father’s earnings.”

Though Randy flourished as an amateur artist and poet.

Keaton moved to New York to study acting in the mid-1960s and as her acting career began to blossom in the 1970s, she and Randy grew apart.

The actress who won an Academy Award for the movie “Annie Hall” in 1977, a Golden Globe for “Something’s Gotta Give” and appeared in the “Godfather” films and “The First Wives Club,” experienced demands on her time as her star rose. “Who could have known how different our lives would become,” she asked rhetorically.

Nowadays, mental illness is talked about more openly to erase the stigma, as Keaton does with her book. Even pro athletes, such as NBA stars Kevin Love and DeMar DeRozan, devote time to discuss and publicize the importance of seeking help for mental-health issues, which both have done themselves.

And there are these sobering statistics: According to Alzheimer’s Disease International, someone in the world develops dementia every three seconds. The number of dementia patients in 2017 was believed to be nearly 50 million. That number is expected to reach 75 million in 2030 and 131.5 million in 2050, especially in lower- to middle-income nations.

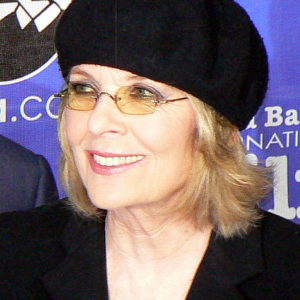

On a lighter note, the Hollywood star known for her avant-garde fashion plate of wearing mostly black-and-white colors (sometimes with ties) and wide-brim hats, told us, “I get way more attention in Washington than in Los Angeles, where I can just go out and walk among the people without that attention. Who do they think they are?”

That line drew a hearty laugh from the audience.

Back home, Keaton is more attentive to Randy. “I want to be a better sister,” she said. More quality time as they have reconnected, like the bunk-bed days. Keaton visits Randy every Sunday at the facility; he can’t speak much, can’t walk much.

So, she pushes his wheelchair into the Fosters Freeze, where she orders ice cream and frozen yogurt for Randy.

Keaton remembered the time as kids when they went to a jagged dirt hill, where she pushed Randy off. He tumbled down, landing on an old sycamore log. Randy ended up breaking his leg. But he never squealed to his parents about Keaton’s shove.

“Randy stayed loyal to me,” she wrote in her book.

Now, Diane Keaton is returning the favor.