GWANGJU, South Korea — Details about what happened here during those terrible days from May 18 through May 27, 1980, remain elusive four decades later.

One of the greatest mysteries is who ordered South Korean army helicopters to fire on crowds demonstrating against the military-led regime in Seoul.

Investigators will have trouble extracting confessions from aging army veterans or finding witnesses beyond those who have long since described what they saw, but hidden documents may be revealing.

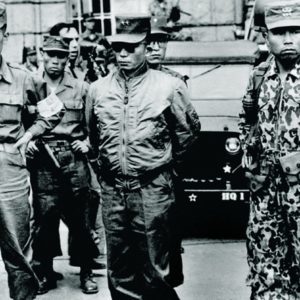

Chun Doo-hwan, the general who seized power in the months after the assassination of President Park Chung-hee nearly seven months earlier, has consistently denied helicopters fired on civilians, but the evidence is overwhelming. Those who saw them firing have already given eyewitness reports.

The pockmarks of bullets slanting in downward trajectories are on display in the renovated Jeonil Building across May 18 plaza from the former provincial government offices that were occupied by student protesters before the final onslaught on May 27.

Chun is not going to alter his denials while on trial for libeling a priest who described the firing from the helicopters. The record is clear even if we don’t know how the order was passed down the chain of command. Could it be that Chun and his friend, Gen. Roh Tae-woo, gave commanders the license to do as they pleased?

The other great mystery that the commission might try to resolve is the American role. A raft of declassified State Department documents shows American concerns, conversations between American and Korean leaders and debate at high levels in Washington about what to do.

As Brad Martin, a journalist colleague who was there at the same time as I, has written, there was still no “smoking gun,” no document in which the Americans advise on suppressing the uprising, much less suggest firing on protesters.

In fact, the State Department has released message traffic that shows the concerns of William Gleysteen, U.S. ambassador to South Korea from 1978 to 1981, one of the most critical periods in the country’s history, before, during and after the uprising.

In one document, Gleysteen reported that “firmness toward the students should be coupled with conciliatory moves in the political area.” Instead, the generals “proceeded with the May 17 crackdown” though “reactions” in Gwangju and elsewhere “had shown the generals to have been wrong.”

The military made a serious mistake, Gleysteen wrote, by “attacking Kim Dae-jung,” the dissident hero and later president, who was jailed well before the students rose up in his name. “I was really more worried at this point about internal miscalculations,” Gleysteen stated, than “about imminent attack from North Korea.”

Evans Revere, then a young U.S. diplomat in Japan, later deputy chief of the U.S. embassy in Seoul, fears “blame for the massacre can be placed on the United States.” One talking point for this position is the claim that Gen. John Wickham, the U.S. commander in South Korea, authorized the movement of the 20th division to Gwangju.

Operational control, however, was a formality. Wickham did not have the power to tell Chun not to send South Korean troops down there and was shocked by what happened.

“The record seems pretty clear that Chun and the generals were lying to the United States about their intentions,” Revere told me in an email. “Using their control of the media to portray the United States as supportive,” they were “making sure that the U.S. was portrayed as complicit.”

Chun “was essentially playing the same game,” the blame game, “that the Left has been playing ever since the massacre.”

The investigation should come up with details that have remained unknown for years along with material that’s already out there. Any inquiry should note Gleysteen’s attempts to persuade Chun of the need for democratic reform for which he had pressed well before Gwangju.

“Our basic concern was that any new political arrangements in Korea be developed in a way which was acceptable to the Korean people,” Gleysteen told a senior Cheong Wa Dae official a month after the massacre.

He wanted Chun to know, “We were particularly disturbed by some anti-American maneuvering within the regime quite apart from anti-American criticism in opposition/dissident quarters.”

The Americans, as the documents indicate, were caught between polarized forces. It is hoped the May 18 commission will focus on that dilemma while ferreting out new material