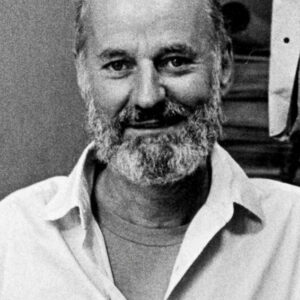

On hearing of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s death last week at age 101, I immediately thought of the bookstore on Haight Street in San Francisco where I gave a poetry reading several years ago. That reading, the fulfilment of a youthful ambition, made me a somewhat belated part, I felt, of a vital branch of America’s literary genealogy. Whatever you call that branch, the Beat Movement or the San Francisco scene, Ferlinghetti was its impresario. A poet, a bookseller and publisher, he devoted his life both to writing words that connect with an audience and to getting the work of others into the hands of readers.

Ferlinghetti is important to American poetry, and to me, because he not only preached that “art should be accessible to all people, not just a handful of highly educated intellectuals,” but he practiced this credo as a poet and part-owner of City Lights Bookstore and Press. He believed, it seems, that everyone, by virtue of being human, is qualified to respond to, enjoy, or even criticize art. For poetry in particular, a respect for the needs of one’s audience is essential, especially since many readers come to poetry with preconceived notions that it is recondite or a riddle to solve.

I see Ferlinghetti as the great poetic populist, an advocate of the view that, as Matthew Zapruder said in The LA Times in 2017, poetry “is our communal language. . . it belongs to the people.” In addition to his importance for the how of poetry, Ferlinghetti was also responsible for liberating what poets can say. By successfully defending Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” in an obscenity trial, he established a precedent that allowed American readers access to previously banned books such as D.H. Lawrence’s “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” and Henry Miller’s “Tropic of Cancer.” Writers could then publish and readers could read about formerly taboo subjects like sex (straight and gay) and drugs. Because of his advocacy of accessibility and free speech, I would call Ferlinghetti the most democratic American literary figure since Walt Whitman.

I am glad that he lived long enough to see his work coming to fruition. A recent NEA report (2018) found that, from 2012-2017, “the share of 18-24-year-olds who read poetry more than doubled.” We are seeing more and more poetry in the public sphere, whether it be “Poetry in Motion” in our subway cars, micropoetry on social media, or Amanda Gorman at the podium for the presidential inauguration and the Superbowl. I look forward to a time when major American events regularly feature an occasional poem and people often pepper their conversation with popular lines of poetry. Ferlinghetti himself, in fact, expressed a similar optimism in his Populist Manifesto: “Poets, come out of your closets, / Open your windows, open your doors, / You have been holed up too long / in your closed worlds … Poetry the common carrier / for the transportation of the public / to higher places / than other wheels can carry it …” Yes, he foresaw, in that vital exchange of words and comprehension that forms the bond between poet and audience, the means to take the American people to new heights.

All of which brings me back to that bookstore reading on Haight Street. I realize now that I felt like a Ferlinghetti that day, because of the colloquial poetry I recited, because of the occasionally R-rated situations I described, because of the exaltation I tried to radiate. The town was his; the scene was his; I was merely a brief surrogate. By writing the way people actually speak, by being an artist and promoter of artists, Ferlinghetti represents what I aspire to in art and life.