When Milton Levine returned from World War II, he had some common, but very pressing, problems.

He didn’t have much money. Which was doubly urgent because he brought a lovely young war bride from France home with him.

Second, he didn’t have a job. With 15 million service members returning to civilian ranks and the economy shifting from wartime to peacetime footing, there just wasn’t enough work for everyone.

Rather than wasting time searching for a non-existent position, Milton went into business for himself. He read somewhere that the best fields for ex-GIs were toys or bobby pins.

There’s no record of how the bobby pins turned out, but toys were a brilliant suggestion. Millions of veterans were marrying and starting families. Overnight, America had a Baby Boom. As kids grew, they wanted toys.

Milton partnered with his brother-in-law and started a mail-order plastic toy business. They placed ads in comic books offering “100 Toy Soldiers for $1.” They sold imitation shrunken heads to hang on car rearview mirrors. And they also sold the Spud Gun. You stuck the gun barrel into a raw potato, then fired the chunk as a projectile. (This was the time before lawyers filed lawsuits at the drop of a hat.) It turned out there was a post-war potato glut, and the partners sold two million in just six months.

Milton was doing ok. He wasn’t getting rich, but he was paying the bills.

Then a pool party changed everything.

Inspiration often strikes at the unlikeliest of times. When Milton’s sister threw a Fourth of July picnic at her southern California home in 1956, she had no way of knowing it would revolutionize the toy industry.

Families were relaxing poolside. Milton spotted a mound of ants and bent over to watch them. He remembered visiting his uncle’s farm as a boy where he dug up ant colonies, put them in Mason jars, and stared in fascination as they built tunnels and crawled around.

Then it hit him: why not build an ant observation toy? With that, he suddenly had a new product unlike anything else. He was already sketching ideas when the fireworks started.

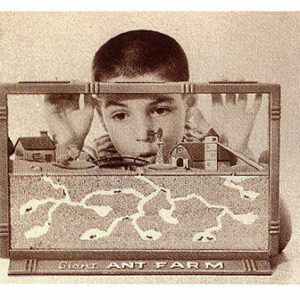

Milton realized buying the ant farm would be a two-step process. He designed a six-by-nine-inch plastic display. It came with a coupon for 25-30 ants, which would then be sent to the buyer. He also discovered permission was needed from each state to send ants via mail. (Hawaii still bans shipping them, by the way.)

The next problem: where do you get ants? It turned out to be surprisingly simple. Ads were placed in local newspapers saying, “Ants Wanted!” and offering a penny per. Soon Milton was deluged with jars full of industrious insects. One guy showed up with an enormous container and demanded $50. When Milton asked how he knew there were 5,000 ants inside, the man dumped them on Milton’s desk and shouted, “You count them!” as he stomped out.

The ant farm went on sale for $1.98. And Baby Boomers immediately went crazy for it, Parents and teachers gave it their blessing for being “educational.”

The fad coincided with the Golden Age of 1950s television. Milton took full advantage of the new medium. He showed his ant farm on Merv Griffin’s and Johnny Carson’s shows, made a fancy executive ant farm for American Bandstand’s Dick Clark, and explained ants’ daily routine to Shari Lewis and her popular puppet Lamb Chop.

Milton was now buying one million ants every week to keep up with demand. Incredibly, the fad never died out. As Milton said in 1991, “Most novelties, if they last one season, it’s a lot. If they last two seasons, it’s a phenomenon. To last 35 years is unheard of.” (And he said that 30 years ago.)

Milton also said, “I found out ants’ most amazing feat. They put three kids through college.” Those plastic ant farms made Milton Levine very rich. He bought out his brother-in-law in 1965 and changed the company’s name to Uncle Milton’s Industries, featuring Uncle Milton’s Ant Farm. For years people joked, “If you’ve got all these ants, where’s the uncle?” So, he gave himself that title.

When he sold his company in 1997 (for a reported $40 million), more than 20 million ant farms had been purchased.

Uncle Milton died in 2011 at age 97. World War II veteran, loving family man, self-made millionaire—It would be hard to dig up a more American success story.