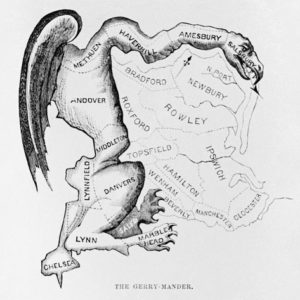

Partisan gerrymandering is in full swing in America following the 2020 Census. In most states, legislators have the power to establish their own districts and both parties work to control the process and create favorable districts that often entrench incumbents and diminish the power of voters to change their leaders. And this year, in those states with independent commissions, even their recommendations are being ignored or undercut by state legislators. All of this gerrymandering is happening, despite the fact that the polling indicates that a significant majority of the American public support redistricting by independent commissions. In the face of such challenges, civic and business leaders need to rally the public support for independent redistricting commissions and collectively work to ensure that the commissions are established and their maps are implemented.

While gerrymandering has been a part of politics since our nation’s founding, partisan gerrymandering is more common, more efficient, and more effective—and therefore more pernicious—than ever before. It is exacerbated in this census cycle by a closely divided Congress, whose control is up for grabs, and a truncated map-drawing timeline due to pandemic-related delays in the Census release. Technology made available to legislative mapmakers is also accelerating the challenge by making it easy to predict voting patterns and to draw districts that largely predetermine election outcomes.

American voters are being harmed in at least two ways.

First, partisan gerrymandering devalues citizens’ votes—their most fundamental rights and protections under our rule of law. When officeholders draw their district lines to choose their own voters—typically to pack the district with their supporters and ensure their own reelections—they impose themselves on the voters who should have the power to choose or reject their own representatives. Of the 435 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, only 37—8.5 percent—were decided by margins of less than 5 percent in 2020, even though the aggregate national vote was as close as 50.8 percent versus 47.7 percent.

So, the 90-percent-plus of voters who live in uncompetitive districts, where there are built-in wide margins for the incumbents who chose those voters, have no meaningful say in who represents them. When the outcomes of elections are foregone conclusions, whether those outcomes favor or disfavor any particular outcome, the demoralizing sense that “my vote doesn’t count” devalues our democracy. Citizens who learn their vote can have no impact soon enough learn not to care.

But the cost of gerrymandering doesn’t end there. Extreme districts—weighted far to one party’s side—lead to extreme elected officials. In districts drawn to be controlled by one party, the general election is meaningless; winning the primary election is tantamount to winning the office. Candidates must turn away from the center and play to the ideological base to win. The more the center is ignored, the more the extremes dominate elections. Finding consensus and workable solutions becomes unnecessary for the winners. Nothing gets done in Washington. The rare actual decisions lean far to one end of the spectrum; when the electoral pendulum inevitably swings the other way, those decisions are pulled up by the roots and replaced with the opposite extreme. Households and businesses do not have the reliable, steady institutions that they need to plan for the future.

The Senate, which is elected according to state boundaries that are not redistricted, might restore some stability, but even that safeguard fails. With gerrymandered districts not just for the House of Representatives but also for state legislatures, the entire “farm team” from which future Senate candidates are chosen is groomed for extremism. The majority of citizens who are somewhere near the center have no candidate for whom to vote.

Nearly nine out of 10 voters oppose gerrymandering. What can we do to restore competitive elections, and bring back candidates who represent the voters?

Redistricting should remain at the state level, but it should be in the hands of nonpartisan, independent commissions, and not be overridden by politicians. Those commissions should be charged with applying neutral criteria to draw fair, competitive district lines. Ten states now have commissions that carry the primary responsibility for redistricting; until such commissions become widespread, the two parties will continue trading punches at the expense of a representative democracy that reflects the will of its citizens.

Nonpartisan, independent commissions, if structured properly, produce fairer, more competitive, and less polarized districts. They eliminate the inherent conflicts of interest of legislators who approve their own districts. And they strengthen the voice of voters, improving the accountability and responsiveness of government to citizens’ views. It is, therefore, no surprise that many Western democracies, including Canada and Great Britain, use this approach.

The two major political parties have little incentive to give up gerrymandering, so it is incumbent on citizens and leaders in the private sector to demand that districts be drawn by nonpartisan, independent commissions and that those commission decisions be respected by state lawmakers. Fair district lines will re-inject competition into our political process and put voters back in charge of choosing our leaders.