The 50th anniversary of the June 17, 1972, Watergate break-in — in which burglars inspired and funded by President Richard Nixon’s re-election campaign attempted to bug the Democratic National Committee offices — stirs memories of a sorry chapter in American history.

Organized by the Committee to Re-elect the President, fittingly referred to by some as “CREEP,” in a time when political savants already fully expected Nixon to win the 1972 election, the bungled operation exposed a sitting president to unrivaled investigation and condemnation. Ultimately, of course, Nixon won in 1972 but resigned under threat of impeachment in 1974.

Much has been made of Watergate’s lasting damage to America’s political culture. Less discussed is the shift toward better governing that followed. Perhaps a bit more skepticism of our government isn’t so bad.

More than a dozen high-ranking Nixon administration officials were dismissed from office, tried for crimes, and convicted, including former Attorney General John Mitchell, who served a prison term. Nixon’s resignation installed an unelected president, Gerald Ford, and led to a political housecleaning.

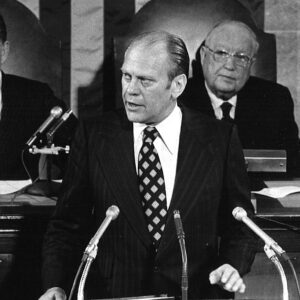

The new president and former congressman had never run for national office, had no real national political base, and had made no presidential campaign promises that begged to be delivered. To add more critical contours to the unique political landscape, Ford’s clear-eyed decision to pardon Nixon almost guaranteed that he would not be elected to a second term. These left Ford free to push for actions that he believed might serve a more significant public interest than politics-as-usual would dictate.

As Mancur Olson argued in his 1982 treatment of the rise and decline of nations, calamities that usher out a previously powerful political class can bring fresh thinking to bear on national problems and, in some cases, reverse periods of prevailing stagflation and decline with improved productivity and rising prosperity.

Yes, the prevailing view among many presidential scholars is that Watergate was a watershed event that destroyed much of the trust we ordinary Americans hold for our country. One can justifiably point to other, more recent scandals and low points in the behavior of sitting presidents who could not countenance losing the power, glory and glitter associated with holding the highest office of the world’s leading democracy.

Indeed, both outlooks may be valid. But I see Watergate as an event that facilitated an energetic and fundamental shakeup in how the federal government regulates the economy. A topic that became dear to the heart of President Ford. Many of the era’s good-government reforms remain in place.

By opening up the government to more scrutiny, Watergate helped pull back the curtain that previously concealed much of the regulatory state. In turn, this led to efforts that made our enormously powerful agencies — those full of unelected rule-makers — more accountable to the people.

For example, because of how Mr. Ford came into office, the “accidental president” was able to establish successfully continue the White House review of newly proposed and existing regulations that put federal bureaucrats on notice. Their proposed actions would have to be cost-effective. This initiated political forces that later administrations led to the complete deregulation of surface and air transportation and to significant revisions in banking regulation and antitrust. These in turn led to dramatically cheaper seats on planes for ordinary people, lower-cost freight, and greater economies of scale and more competitive American manufacturing.

Watergate’s shattering of the status quo at the top of our national government made it possible for fresh ideas to enter the agenda. Some of these had been evolving for years and needed a headwind. There were reform-minded employees in regulatory agencies hoping for the day when their knowledge could become viable. There were academics hoping for an opportunity to engage in meaningful discussions for change. And there were think tanks like the Brookings Institution and American Enterprise Institute generating proposals and awaiting the opportunity to give leadership to new debates.

As Steven Johnson explained in “Where Good Ideas Come From,” there was an “adjacent possible” in our world that previously had no wide recognition. When it was made visible, it became part of a lively agenda for action.

Fifty years later, we have an economy suffering from inflation and a divided government lacking a coherent political willingness to deal with pressing trade, immigration, environmental and foreign policy issues. Perhaps this is a good time for leaders to re-examine fundamental Watergate learning. They might even find some possibilities that have been here all along.