Remember 1998? Pokemon games flew off the shelves, Google launched a search engine, and Americans lined up to see whether Bruce Willis would save the world from Armageddon. But few remember that certain auto manufacturers (with Toyota leading the way) asked the Federal Communications Commission to grant them a huge spectrum band for a new technology called Dedicated Short-Range Communications (DSRC) that the manufacturers promised would allow cars to “talk” to each other for safety, e-commerce and entertainment.

It worked. The FCC gave the manufacturers 75 megahertz of wireless spectrum in the expectation that DSRC would work. It didn’t.

Twenty years later the spectrum is still almost completely unused, and DSRC is stuck in neutral. Americans’ demand for Wi-Fi and other wireless broadband — and the spectrum needed to deliver it — has exploded. But that 75 megahertz of spectrum is still waiting for DSRC to finally arrive.

After decades of technological advancements, DSRC is a floppy disk in a WiFi world. But despite all of this, the Department of Transportation still thinks that DSRC can drive in the fast lanes of today’s digital age of communication.

In December 2016, during the final weeks of the Obama presidency, the Transportation Department used government muscle to engineer a “midnight raid” of the spectrum and force DSRC on the economy. It proposed a rule that would have required every car in America to use this specific, obsolete and controversial technology. The rule received little public attention, but it would have raised the price of every new car and hurt innovation in both the automotive and telecom sectors.

If it had been adopted, the proposed mandate would have subsidized DSRC, forcing investment into an outdated but government-favored technology and away from competing technologies. Just as troublingly, the government would have cemented DSRC in a large block of important mid-band wireless spectrum, effectively tying the FCC’s hands as it looks to free up more spectrum to get faster, better wireless broadband to all Americans.

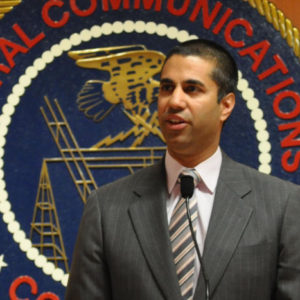

Fortunately, President Trump quickly appointed Elaine Chao and Ajit Pai to lead Transportation and the FCC, respectively. Chao and Pai have been widely recognized by conservatives as two of the most effective agency leaders when it comes to how their respective agencies have implemented conservative policies with a focus on both deregulation and positive economic effect.

Chao wisely delayed the regulatory overreach of the the DSRC mandate. According to its own cost estimate, it would have imposed total costs of $108 billion. And in its recently released Automated Vehicles 3.0 Guidance, Transportation reaffirmed that it will take a technology-neutral approach to connected vehicle technology that “does not promote any particular technology over another” and is open to sharing the band with Wi-Fi.

This is good news. A technology-neutral approach will ensure that heavy-handed government intervention does not stifle the development of new, better automotive safety technologies. But there are some who still want to achieve at the FCC what the Obama administration almost pulled off at Transportation — favoring DSRC or other automotive technologies through spectrum subsidies and regulations.

This administration shouldn’t stand for it. Now is the time for FCC, Transportation and stakeholders from the broadband and auto-safety industries to move forward with creative solutions to address the spectrum needs of both the automotive and the Wi-Fi sectors. Spectrum is too valuable a national resource to let 75 megahertz in the prime mid-band range lie fallow any longer. And under no circumstances should government ever subsidize one set of technologies.

The 5.9 GHz band in question is adjacent to the most important Wi-Fi band in the world, and opening it for consumer use would promote deployment of high-speed gigabit Wi-Fi on a large scale. With Wi-Fi demand growing rapidly, this additional spectrum is needed to keep this ubiquitous technology working smoothly and to reach higher speeds. This is an economic issue. Unlicensed spectrum contributed more than $500 billion to the U.S. economy in 2017, and it is critical to positioning America for success in 5G deployment.

The FCC seems poised to do the right thing, on a sensible, bipartisan basis. Republican commissioner Michael O’Rielly and Democratic commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel noted in a 2016 joint statement: “We believe this slice of spectrum provides the best near-term opportunity for promoting innovation and expanding current offerings, such as Wi-Fi. That’s because combining the airwaves in this band with those already available for unlicensed use nearby could mean increased capacity, reduced congestion and higher speeds.”

The administration should not repeat the mistakes of the past. We should not reserve finite, economically valuable spectrum only on the hypothetical possibility that it may be useful for automotive connectivity in the future. The FCC should open the 5.9 GHz band to unlicensed use, while committing to work with Transportation to address future spectrum needs for connected and automated vehicles.