Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) made several stops in the First-in-the-Nation Primary State on Wednesday, meeting with Second-Amendment supporters at Londonderry Fish and Game, business leaders at a Republican legislator-owned pub in Concord, and parents at Founders Academy, one of New Hampshire’s newest public charter schools.

Founders Academy opened its doors for the first time this September to 6th and 7th grade students, with plans to expand yearly with growing demand. A repurposed manufacturing facility in the shadow of the Manchester Airport runway, the building was completely renovated to host the public charter school. Thomas Frischknecht, the school’s founder, who is from Amherst, has experience developing charter schools in New Hampshire. He says he was inspired by the values of America’s founding fathers to cultivate an academic environment that emphasizes classical learning, the English language arts, and the leadership skills necessary to compete and contribute to a global society.

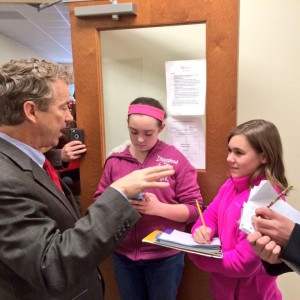

It is with this backdrop that presidential hopeful Paul came to discuss his positions with regard to education, along with his staunch opposition to the Common Core standards.

The debate surrounding the Common Core State Standards is both contentious and complicated. It has become, as Frischknecht observes, a political football, with 2016 hopefuls attempting to distinguish themselves from a crowded and growing field of potential candidates. Pundits have abandoned discussion of the policy itself, and instead focus on the political repercussions surrounding a potential candidate’s support or opposition to Common Core.

Although Common Core originated as a bipartisan partnership between state governments and is endorsed by the National Governors Association, some Republicans have attacked the standards. Overwhelmingly, Republican Governors continue to support Common Core, including many of the potential 2016 hopefuls. Some have applied cosmetic distance, including Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, who has called for schools to not be required to use the standards. Though such a requirement can only come from the state level, a point often misunderstood in the debate.

Also, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie issued an executive order creating a commission for the evaluation of the state’s Common Core implementation.

The strongest opposition has come out the Bayou State, where Gov. Bobby Jindal has made his recently-acquired disdain for the education standards explicitly clear last summer by filing suit against the Obama Administration, alleging Washington was bullying the states to comply with Common Core.

Public and impassioned displays of opposition are understandable considering the manner in which the Common Core debate is being treated by the media’s 2016 election coverage. It is accepted a priori that supporting Common Core is an obstacle that could prevent a candidate from securing the Republican Presidential nomination.

However, if strategists and commentators were to take a step back and discuss the policy itself in earnest, we might find that the issue is not in fact as polarizing and contentious as we are led to believe.

This brings us back to Founders Academy focus on the language arts, and the school’s appreciation for freedom and liberty.

The Common Core debate has been characterized by a number of oft-repeated claims and colloquialisms that have shaped public perception. Phrases like “lowest common denominator” and “one size fits all” or “top down” appear in nearly every education policy discussion, and while casual language is often necessary to succinctly articulate complex policy issues, this kind of rhetoric can obfuscate the issue altogether.

In his address to the audience of Founders Academy, Sen. Rand Paul captured their attention by stating, “The problem with education in our country is it’s stagnated because it’s from the top down.” He continued this thought, “If you get to curriculum, some of the stuff may be good or bad but it shouldn’t be centralized because innovation comes from freedom of choice,” at which point the Senator introduced the straw-man of the Common Core discussion. Sen. Paul solicited applause and laughter in his description of the “danger to nationalizing this and having the curriculum or way we teach kids come from Washington,” which has resulted in widely-criticized, so-called ‘common core math’ problems that bewilder students and parents alike.

While the idea of a “national curriculum” created by Washington bureaucrats and foisted upon the States and school districts is upsetting to many Common Core opponents, it is ultimately a misnomer, or at the very least, a misrepresentation of the actual ramifications of Common Core. It must be noted that Sen. Paul did not create the myth of a “national curriculum” and his employment of the phrase does not suggest a willful act of deception on his part, but is just one example of the manner in which the topic is debated and perceived by voters.

Common Core is not a “curriculum.” It is a set of academic benchmarks that states agree students should meet at the end of each school year. Such standards have always been set at the state level, with local districts making curriculum decisions. Educators retain the discretionary prerogative to present material and instruct their students as they see fit, and as long as they meet the minimum requirements, schools and teachers still create their own lesson plans.

This is not to say that the policy does not present significant challenges to the districts, schools, and educators that are tasked with the New Hampshire requirement to administer the new Smarter Balanced standardized test and meet other new requirements, but the fact of the matter remains, there is no such national or centralized curriculum.

Qualified educational professionals will point out that the new standards themselves, in effect, determine the curriculum despite the absence of any lesson plans handed down from Washington. As Mr. Frischknecht points out, New Hampshire still requires a public charter school, like Founders Academy, to administer the Smarter Balanced test, which presents quite a quandary. He figures that there are three possible responses to the Smarter Balanced requirement. He could either have his teachers “teach to the test, which we will never do.” They could also seek out an exemption (for which there is no established procedure or protocol). For this year, they have decided to simply “roll the dice” as he puts it, by administering the test, which may or may not include content that his students have not covered and for which they may not be prepared.

The new standards are exactly that when it comes to curricula, as some Common Core proponents will tell you. “There were minimum standards before and there are even more rigorous standards now,” says Pittsfield resident Nicholas St. Germaine, who teaches middle school math at Deerfield Community School. “The curriculum is developed in the same way as it was before the new standards and before the new test,” he clarifies, and curriculum development remains the responsibility of the school districts and educators. In fact, when it comes to actual lesson plans, or how teachers are expected to prepare their students for new benchmarks and the accompanying assessment, administrators are more or less left to fend for themselves when it comes to developing the lesson plans that will allow their students to perform well on the new Smarter Balance assessment. This is another problem entirely, and is the main sticking point of groups of educators and teachers unions, but this difficulty further highlights the discrepancy between the facts and the widely-disseminated talking points surrounding Common Core discussion.

Ultimately, New Hampshire voters will be tasked with making their own determinations regarding Common Core and other issues before going to the polls next year. However it is the duty and responsibility of the candidates and commentators to engage the voters in meaningful policy conversations. Words matter, and the language we use in these conversations today should properly prepare the voters to make informed decisions on Election Day, not just capture their attention or incite their applause.