Last week, former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice poked at the belly of liberals and Democrats with this observation:

“I don’t really care if we’re colorblind, but I would like to get to the place that when you see somebody who is Black, you don’t have preconceived notions of what they’re capable of, who they are — by the way, what they think, which is I think a problem of the left.

“You look at somebody who’s black and you think you know what they think, or you at least think you know what they ought to think.”

Translation:

A) Rice is unapologetic for being a Black female Republican,

B) Rice is advocating more diversity of thought and less stereotyping,

C) Rice is adamantly opposed to group-think,

D) Rice is saying that Americans shouldn’t box themselves in via a monolithic prism.

Section D is most fascinating here. Some Black folk in the United States openly advocate the virtues of diversity, but when it comes to “Black diversity,” the notion can go off the rails. That means if one disagrees with what’s considered to be the “official” stance that “all” Black folk should profess, the name-calling begins.

We can vividly see the intra-racial, Black-on-Black tensions when phrases such as “coon,” “Uncle Tom,” “don’t invite him or her to the cookout,” “sellout” are thrown around like Frisbees.

Just check social media.

Rice’s assertions during an appearance at the annual Aspen Security Forum came on the heels of a survey about political public speaking conducted by the CATO Institute, a libertarian think tank in Washington.

According to CATO’s survey, nearly two-thirds of Americans — or 62 percent — believe today’s polarizing climate prevents them from voicing their political beliefs because others might find them offensive. Americans who self-censor have increased from 58 percent in 2017.

And these fears cross partisan lines. Majorities of Democrats (52 percent), independents (59 percent) and Republicans (77 percent) agree they have political opinions they are afraid to share.

Is that 62-percent overall figure a result of people feeling the spirit of altruism or is it a product of intimidation through bullying?

Dr. Kevan Harris, a professor of sociology at UCLA, offers another possible explanation: information overload. “I think this new social movement has caught a lot of people off-guard,” Harris told InsideSources. “And some people truly may not feel they really know what to say anymore.”

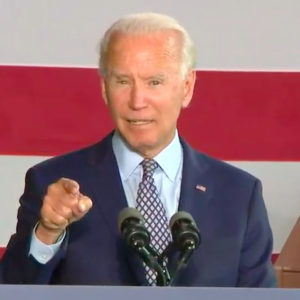

Which means they don’t want to be in the position that presidential candidate Joe Biden often finds himself. Biden is known for making head-scratching remarks.

Some call them gaffes; others call them his true, inner-most feelings.

During the recent virtual, joint convention featuring the National Association of Black Journalists and the National Association of Hispanic Journalists, Biden, obviously irked by a question involving his cognitive acuity, asked a Black anchorman, Errol Barnett of CBS News, if he was a cocaine junkie and later suggested that the Latino population is very diverse but Black folk aren’t.

In responding to a question by NPR’s Lulu Garcia-Navarro, Biden answered: “By the way, what you all know but most people don’t know, unlike the African American community, with notable exceptions, the Latino community is an incredibly diverse community with incredibly different attitudes about different things. You go to Florida, you find a very different attitude about immigration in certain places than you do when you’re in Arizona. So it’s a very different, a very diverse community.”

Some critics interpreted Biden’s comments as implying that Black folk are entrenched in group-think and cannot form individual opinions.

Maria D. Burgos, consultant and professional learning developer in the field of cultural proficiency for Prince William County Schools in Virginia, explained that the socio-political differences among Hispanic/Latino communities are more so about race. “The Latino community, which identifies as Hispanic/Latinx/Afro-Latino, represents 21 Spanish-speaking countries of origin,” Burgos told InsideSources.

“Community members who identify as white or are white-passing may differ in attitudes from other members of the community who identify as people of color. These varying viewpoints about immigration and equity are not based on state-to-state residences or the countries of origin but rather through the diverse, racial experiences within the community.”

Still, Biden knows he can easily skate away from perceived, controversial racial comments because most Black people (as in 85 to 90 percent) will vote for him regardless of his musings, proclamations and utterances.

Biden later issued a clarification, saying on Twitter, “In no way did I mean to suggest the African American community is a monolith — not by identity, not on issues, not at all.”

With that, we also get a clearer picture of why so many Americans would rather keep their political opinions to themselves: It means the silent treatment in response to political questions nullifies the need for clarifications, apologies, walk-backs and moonwalks.

Additionally, there are a couple more compelling revelations in the CATO study:

— Staunch liberals (58 percent) are the demographic most likely to allay their fears and voice their opinions; conversely, staunch conservatives (77 percent) are more likely to maintain that fear.

— The higher a person’s educational level, the more likely one is to self-censor their public speaking. For instance, 44 percent of Americans with post-undergraduate degrees believe their political opinions could cost them their careers; conversely, only 25 percent of high school graduates linked their opinions to possible job losses.

But Rice, a professor of multiple disciplines at Stanford University, broke the mold on self- censorship. She unabashedly criticizes liberals, the space that most Black folk in the United States occupy.

Therefore, stereotyping doesn’t fly in her space.