TOKYO ― Kim Jong-un must be happy now. What could have made him feel better than for his friend President Donald Trump to dump John Bolton as national security adviser?

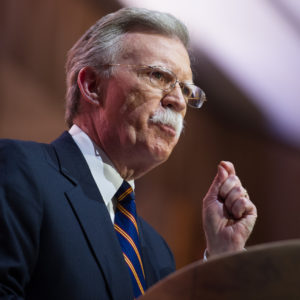

As Trump made clear, he and Bolton disagreed on many things, notably the Middle East, Iran and Afghanistan. Bolton’s hawkish instincts would have appeared to fit in perfectly with Trump’s views, but Bolton was considerably more extreme. Although he served only briefly in the armed forces, avoiding Vietnam, he appeared far more eager for military intervention than did his boss.

Bolton’s hawkish views were most evident, though, in his arguments against concessions to North Korea. North Korea accused both him and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo of having persuaded Trump to walk out of his February summit with Kim in Hanoi after advising him the North needed to do much more than offer a vague promise to shut down its aging nuclear complex at Yongbyon while maintaining its nuclear program at other sites in the country.

The dismissal of Bolton gives North Korea all the more reason to stick to its guns ― and nukes. The North’s vice foreign minister, Choe Son-hui, made clear, in a statement proposing talks with U.S. negotiators, that the North was not budging on the nuclear program that the U.S. insists it has to abandon.

Kim Jong-un appeared to have carefully calculated a one-two punch. The North’s contempt was plain after it sent two projectiles, whether missiles or rockets, flying about 330 kilometers over the waters between North Korea and Japan.

Like a teacher addressing a student, Choe said she believed the U.S. would come up “with a proposal geared to the interests of the DPRK and the U.S.” on the basis of “the calculation method acceptable to us.”

The lesson was the U.S. had better agree to a “step-by-step” approach under which North Korea refrains from testing its nukes and intercontinental missiles while the U.S. removes sanctions. There was, of course, no hint that another “calculation,” including on-site inspections, would be negotiable.

The trouble with this approach is that North Korea has been building ever more nuclear warheads since its last, biggest, nuclear test two years ago this month. The North conducted its last long-range missile test two months later but is working on long-range missiles with which to fire warheads at distant targets, including the U.S.

The possibilities for escalation all around the region are clear. Stephen Biegun, the U.S. negotiator on North Korea, asked rhetorically in a recent speech if “voices in South Korea or Japan and elsewhere in Asia” might “need to be considering their own nuclear capabilities.” That remark played on demands that those countries should come up with nukes on their own for self-defense rather than rely on their American ally.

The last thing South Korea’s liberal President Moon Jae-in, in his quest for reconciliation with the North, would consider would be a South Korean nuclear program while opposition to his policies toward North Korea is growing.

Much of the protest now focuses on Moon’s choice for justice minister, Cho Kuk, who once led a socialist organization dedicated to revolution.

Sentiment against Moon has intensified with the indictment of Cho’s wife for forging certificates to get her daughter into college and medical school. The media also focuses on financial dealings amid reports fueling claims of hypocrisy among the leftists in Moon’s government.

Trump, however, remains ostensibly unperturbed and welcomes the prospect of talks between Americans and North Koreans as promised when he met Kim Jong-un in Panmunjeom at the end of June. Against warnings from Bolton, he has consistently said he’s not worried about short-range missile tests and believes “having meetings is a good thing, not a bad thing,”

As for Pompeo, he has not commented on North Korea Foreign Minister Ri Yong-ho’s description of him as a “poisonous plant” and would no doubt welcome the chance to see Ri in New York during the annual session of the U.N. General Assembly. Such an encounter would seem unlikely, however, unless Ri changes his decision not to attend.

All of which leads Leif-Eric Easley, international studies professor at Ewha Womans University, to see two possible scenarios. First, the U.S. and North Korea “make an interim deal so North Korea can get economic benefits and Trump can claim a victory before the 2020 election.” Or, second, “Trump will claim progress, hoping North Korea doesn’t test an ICBM or nuke before the election” while Kim looks for a post-election deal with whoever wins.