China is behaving like a caged beast — growling, menacing, lashing out and baring its teeth at potential enemies on all sides.

In the far northern reaches of India, Chinese forces have challenged Indian troops along what’s called a “Line of Actual Control” (LAC), established after the Chinese nipped off parts of Indian territory in a flare-up nearly 60 years ago.

I was in India at the time, and I was there again seven years ago when the Chinese again challenged India along the LAC.

Now the conflict is much worse. About 20 Indian soldiers were killed in the latest clash, and India would not seem to have the strength to stand up to incessant Chinese bullying even after moving up tanks in a defensive posture that the Chinese could probably brush aside if they decided to invade in earnest.

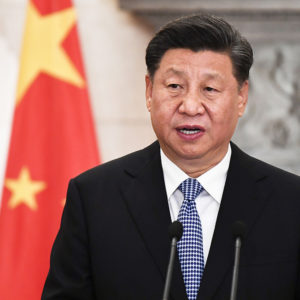

China, however, is facing so many hot spots that President Xi Jinping, masterminding his forces as if he were standing before a huge map, arrows pointing here and there, deciding where to go and how hard to push, might think it’s not a good idea to press deeper into India.

Not while the United States persists in sending aircraft carriers and other weaponry into the South China Sea, which China claims as its own and is proving the point by enlarging air and naval bases on strategic islands.

Growing restive, angered, looking for a fight, the Chinese are intensifying the pressure on Taiwan, the island state off its eastern coast that China goes on and on about, claiming it as part of the mainland.

Xi knows, however, that he cannot quite risk a war for Taiwan as long as it’s defended by the United States, but he’s found a much easier target in the form of Hong Kong, the one-time British colony that became part of China in name only after the British left in 1997.

Flouting the deal under which Hong Kong was supposed to be able to remain essentially on its own, self-governing, for 50 years, the Chinese are now firmly asserting their authority in the face of riots and demonstrations that challenged Chinese authority.

Now a new law enacted at President Xi’s behest means his police and soldiers, if necessary, can pretty much do as they please while Hong Kong citizens holding old British colonial passports flee elsewhere, mostly to Britain. Chinese from the mainland can only wish them good riddance even if they appeared dismayed by the decision of thousands to look for homes in more hospitable settings.

Up the coast, not far from Taiwan, the Chinese are almost daring the Japanese to increase their defenses around the Senkakus, an outcropping of small islands to which Japan tenaciously clings even though they are uninhabited.

China has been claiming Diaoyu, the Chinese name for the islands, ever since a U.N. team nearly 50 years ago concluded that deposits of oil and natural gas probably existed near them though no one has confirmed the presence of such resources.

The Japanese actually took over the islands in 1895 when they also acquired Taiwan as a result of their victory over China in a war for supremacy in the region. Japanese Coast Guard vessels now defend them from encroaching Chinese fishing boats and other craft, firing water from powerful hoses if they venture too close, but that defense may not be enough.

The next step for Japan would be to have its navy warships patrolling the waters, inviting attack that could turn into a war that neither side wants, at least for now.

Which brings us to Korea, North and South, and the Yellow Sea. China does not have to risk war for the Korean Peninsula. The North Korean regime could not exist without the constant support of China, which supplies the North with all its oil and half its food along with a host of other products.

And South Korea, eager to renew dialog with North Korea in the quest for reconciliation, now has to appeal to China to promote the next step in inter-Korean interaction.

As South Korea’s biggest trading partner, China would appear to hold the cards.

Much as they might want to appear totally cooperative with both China and North Korea, President Moon Jae-in and the men around him face the issue of what to do about their relationship with the United States, particularly the mutual defense treaty that’s been in effect since soon after the Korean War.

As in the case of all the other fronts around its periphery, the Chinese haven’t quite decided how far to go in defending their erratic, unpredictable ally. They appear to be waiting for just the right moment ― maybe when the United States has again reduced its troop strength in the South, now around 28,500.

In a great balancing act, Xi has to decide where to punch and jab before delivering the final blows that would make China, undeniably, the strongman of Asia.