Lawsuits against energy companies demanding remunerations for the costs of climate change won’t solve the problem, especially when the United States is not producing the “lion’s share” of greenhouse gas emissions, said a leading expert for environmental law and policy.

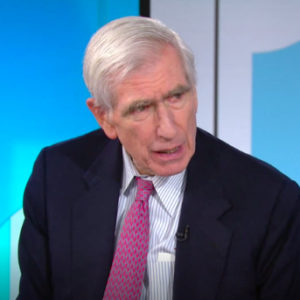

“Rifle-shot lawsuits city by city in courts that have no capacity to deal with actual issues of this complexity is the wrong way to go,” said C. Boyden Gray on a teleconference hosted by the Federalist Society.

The call was to provide an update on the 14 climate-change lawsuits currently pending in the U.S. courts system, including one from the city of Baltimore in which a request for an emergency stay from the oil and gas companies is pending before the U.S. Supreme Court. Gray noted that the Supreme Court granting a stay in state court would be “very rare.” The energy companies want the case moved to federal court where other similar cases have been rejected; Baltimore City Solicitor Andre Davis said the companies are afraid to have the case heard before a state court jury.

Gray, however, said that none of the lawsuits will have the intended effect. He predicted that the cases would eventually be dismissed, mentioning that the Clean Air Act and any actions taken by Congress as the primary authorities for these matters.

Gray served as White House Counsel for President George H.W. Bush and was instrumental in enactment of amendments passed in 1990 to the Clean Air Act, the Energy Policy Act of 1992, and the cap-and-trade system for reducing rain forest emissions. The Montreal Treaty signed in the late 1990s helped eliminate ozone-depleting emissions, and Gray said its success in the U.S. was in part due to the market-based approach taken toward compliance.

“Mechanisms that use the forces of the marketplace are far more effective and cheaper than the regulations that EPA and state EPAs rely upon,” Gray said. “There really is a remarkable difference.”

And whatever steps the U.S. takes to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, Gray noted, the increasing reliance on coal for energy in Asia will still remain the major driver of continued emissions growth. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. greenhouse gas emissions decreased from 2016 to 2017 by 0.5 percent. In 2017, emissions were 13 percent below 2005 levels. The World Resources Institute noted that China’s annual growth rate for coal consumption from 2000 to 2013 was 8.8 percent.

Despite increasing success in the U.S. tackling emissions and moving from coal and oil to cleaner energy sources like natural gas, court cases blaming energy companies for the consequences of climate change keep piling up. Gray referred to the lawsuits as “litigation movements” and said they “tend to come in waves.”

In June, New York Supreme Court Judge Barry Ostrager allowed the state’s lawsuit against Exxon to proceed. Then-state Attorney General Barbara Underwood initially filed it under the Martin Act, which can be used against corporations accused of fraud.

Gray, though, said the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has reviewed similar claims under the Martin Act and declined to prosecute. The New York trial is expected to begin later this month under the supervision of current New York Attorney General Letitia James. Gray insisted, though, that the courts were not the proper venue to address climate change concerns.

“There is pressure on Congress to do something,” he said, suggesting that a bipartisan solution could be found in which market incentives such as a cap-and-trade system was enacted in exchange for suspending carbon regulations. But the prospects of that are slim.

“There are a lot of very powerful environmentalists who won’t agree to that under any circumstance,” Gray said.