For a century, the great philosophical divide in America has revolved around the locus of decision-making. Are details of our lives to be determined by ourselves or by centralized experts? Should governments prohibit individual risk-taking or should we be free to take chances? Which is better: a tidy world planned from on high, or a messy world improvised at street level?

My 2014 monograph, “Fortress and Frontier in American Health Care,” argued that the centralized, risk-minimizing, tidy ideal (the “Fortress”) dominates thinking in health care, while the individualistic, risk-taking, messy view (the “Frontier”) has driven the explosion of innovation in information technology.

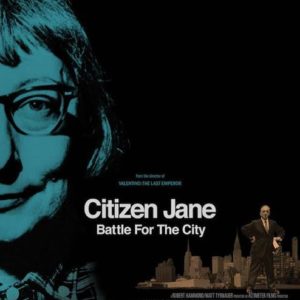

The other night, my wife and I watched a dramatic rendition of Fortress versus Frontier: “Citizen Jane: Battle for the City” — a 2017 documentary about the titanic struggle between New York’s urban planner Robert Moses and journalist Jane Jacobs. For me, the film has lessons about health care in 2018.

Moses was New York City’s master builder throughout the mid-20th century. Immensely powerful, he bulldozed neighborhoods to make way for vast expressways, housing projects and parks. Jacobs was a journalist (disparaged as a meddlesome “housewife”) who gathered a movement to halt Moses’ overreach.

Today, many (me included) tend to remember Jacobs as a visionary and Moses as a despot who scarred a great city. But both clearly sought the betterment of New Yorkers.

Moses preferred towering, neatly geometric housing projects, severed from their surroundings by impassable expressways. He demolished communities and exiled residents, saying, “I raise my stein to the builder who can remove ghettos without removing people as I hail the chef who can make omelets without breaking eggs.”

In the late 1950s, Moses decided to bisect a much-loved park with a high-speed expressway. Jacobs, whose children played in the park, begged to differ. She wrote and spoke and organized people — mostly women, initially — to scuttle the plan. It worked.

Jacobs summarized her revolutionary view of cities in her “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” a broadside against urban planners’ obsession with orderly, sanitized, rectilinear cities. For Jacobs, messy serendipity was what made cities lively, safe and productive. Messiness meant new buildings next to old, commercial next to residential, and activity at all hours of the day and night — anathema to planners.

Above all, hers was a vision of decentralization, saying, “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”

She concluded that safety didn’t come so much from professional police officers as it did from the thousands of eyes on the streets: pedestrians, drivers, merchants, customers, diners — eyes that were absent in Moses’s barren, windswept housing projects.

Jacobs recalled a conversation with a Boston urban planner who said the city’s heavily Italian North End was a mess and needed massive urban renewal. Jacobs said she found the neighborhood vibrant and chaotic and exciting. The planner said he, too, liked the North End and often went there for recreation, but reiterated that it was a mess and needed to be rebuilt. The streets were crooked, the sidewalks narrow and clogged with pedestrians walking and children playing.

Later, Jacobs found that North End had extraordinarily low crime rates. Though a relatively poor neighborhood, people wandered at all hours with little fear of crime. A local community leader told her, “I have never heard of a single case of rape, mugging, molestation of a child, or other street crime of that sort in the district.” In contrast, Boston neighborhoods that conformed to planners’ ideals were often cesspools of crime and disease.

What does all of this have to do with health care? While listening to the documentary, I thought, “In health care debates, practically everyone is Moses, and hardly anyone is Jacobs.” Liberals calling for single-payer want the federal government to be Moses. Conservatives supporting certificate-of-need laws or limitations on nurse practitioners prefer that states (or perhaps professional medical societies) be Moses.

Few in the health care debate call for the messy, decentralized, individualistic decision-making that Jane Jacobs wanted for cities. And this absence, I believe, is the major reason that health care innovation has grown sluggish and health care debates are so vitriolic.