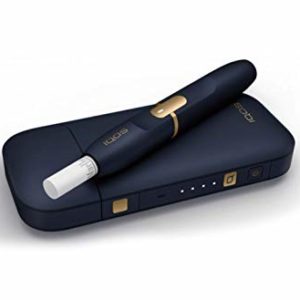

When Philip Morris International (PMI) reacted to the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) approval of a modified risk tobacco product marketing order for its proprietary IQOS heat-not-burn product, it heralded it as a broader public health victory.

The FDA confirmed that IQOS eliminates a traditional cigarette’s burning characteristics by heating the tobacco sticks to a vapor aerosol.

This product is said to significantly reduce the production of harmful and potentially harmful chemicals adding that the company was able to demonstrate that IQOS reduces a human body’s exposure to toxic substances, marking the modification of risk characteristics in the product. It is crucial to note that these sorts of smoke-free nicotine products are not free of risks onto the body, as they still demonstrate modified risks.

“Data submitted by the company shows that marketing these particular products with the authorized information could help addicted adult smokers transition away from combusted cigarettes and reduce their exposure to harmful chemicals, but only if they completely switch,” said Mitch Zeller, director of the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products.

The FDA hasn’t ruled that IQOS is safer than cigarettes, to reiterate. Note that the order, still, doesn’t mean that IQOS is still a viable means for people to quit smoking and reaching complete nicotine cessation. That said, the IQOS MRTP marketing order is a benchmark case of how the regulatory processes under the Tobacco Control Act work.

Swedish Match AB is the first and only other company to obtain MRTP marketing orders from the FDA for varieties of their snus tobacco and nicotine pouch products. If anything, the process works and still present a favorable outcome for many companies trying to comply with the mandatory PMTA regulations.

Barring the challenges small companies face with PMTA, the opportunity for products to confirm modified risk characteristics is a promising prospect. Electronic cigarettes and vaping devices are still considered a safer alternative to cigarettes by public health groups.

Public Health England, notably, endorses regulated e-cigarettes as 95 percent safer than cigarettes. Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention scientists note that these products are somewhat safer than cigarettes.

Consequently, such developments as those discussed here should merit reconsideration for arguments in favor of product prohibition and further restrictions. Using the MRTP regulatory framework, it’s clear that public policy can and should be designed to promote risk-reduced alternative products for smokers looking for an off-ramp from smoking.

An MRTP approval is still a decision that allows tobacco consumers to use products authorized by the FDA that are smoking alternatives like e-cigarettes, which are currently in a state of more aggressive regulatory uncertainty, as I noted. The FDA has stressed, once more, that this decision does not mean IQOS products are safe.

Preferably, smokers should still do all they can to reduce their exposure to harmful chemicals. IQOS, for instance, will work if only smokers switch entirely to this delivery method. That’s a harm minimization, regardless of the mode of delivery the specific nicotine user prefers.

By continuing the rhetoric to ban smoke-free products, the public health is threatened, and the years of PMTA policymaking and business accessibility are lost. I implore critics to keep in mind that prohibition is still prohibition, even by any other name.

Tobacco control proponents should consider the potential public health benefits of smoke-free products.

At the same time, regulators should continue to be proactive with all stakeholder groups — industry included — to reach a measured consensus at the nexus of individual autonomy, commercialization, and public health.