The stories from Indian Country are chilling.

Native American women face violence at rates ten times higher than the national average. Half of them will experience some sort of sexual violence and 84 percent will experience violence of some sort. For native adults overall, the numbers are closer to 4 out of 5. These numbers were the subject of a grim and emotional hearing before the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs on Wednesday, where senators berated FBI, National Institute of Justice (NIJ) and Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) officials for their mishandling of crime on tribal lands.

“You are the cop on the beat,” Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D, N.D.) told the officials “When these crimes go uninvestigated, go unsolved, go ignored for long periods of time, that’s your failure. That’s not the community’s failure.”

The committee hearing was sparked by the release of a report from the Urban Health Institute in Seattle, WA, highlighting hundreds of cases of missing native women who seemed to have fallen between the cracks. Part of this is due to problems of jurisdiction. Tribal police handle some offenses on reservations, but felonies and missing persons cases are the responsibility of federal agencies. Meanwhile, information sharing between these groups is poor.

A lack of data is part of the problem, agreed Charles Addington, deputy associate director of the BIA’s Office of Justice Services. He told the committee that the BIA collected missing persons data from tribes on a monthly basis and submitted its findings to the FBI to be included in its “Uniform Crime Report.” The FBI, in turn, releases reports on missing persons quarterly.

After that, something seems to be breaking down. The Uniform Crime Report doesn’t track missing persons or domestic violence statistics. Instead, the BIA partners with the Department of Justice, which maintains its own database of missing persons.

The FBI has a task force of its own dedicated to missing Native Americans, but somehow the resources don’t seem to be enough.

“Our program includes more than 140 special agents, 40 victim specialists and 36 field offices. In fact, 33 percent of the FBI’s victim specialists and over 50 percent of the FBI’s child and adolescent forensic interviewers work directly with victims and families in Indian Country,” said FBI Criminal Investigative Division Assistant Director Robert Johnson.

The officials couldn’t agree on the best way to solve the problem. Gerald Laporte, director of the NIJ’s Office of Investigative and Forensic Sciences, spoke of adding additional fields, including tribal affiliation, to a federal database of missing persons. Johnson praised a new name search algorithm for the FBI that enhances the ability to search for native names. Addington said there needed to be more coordination between different law enforcement groups.

None of their answers satisfied Montana Sen. John Tester (D), who grew heated when he pressed the witnesses for answers.

“Something’s not happening here that needs to happen,” he said. “It happens in other parts of the country, but it isn’t happening when it comes to indigenous women.”

Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R) agreed, criticizing law enforcement in her own state for prioritizing environmental crimes over crime in native communities.

“When you can receive a higher punishment for poaching a moose than for violating a woman, we have a problem,” she said.

The hearings also demonstrated the lack of relationships between federal law enforcement and tribal communities. Although information sharing protocols are clearly in need of reform, a lack of trust between tribe members and law enforcement means that it is difficult for investigating officers to get tips and leads from the community. During questioning, Addington mentioned briefly that investigations were often halted because of a lack of tips from people who new the victim. Unlike databases, this lack of trust was not discussed.

In fact, as Congress works to address this problem before the end of the session, the focus is primarily on databases. Wednesday’s hearings came as lawmakers are working to push legislation adding a tribal identification field to the DOJ’s missing persons database through the House before the end of the session.

Though a step in the right direction, increased information sharing will not solve all of the native communities’ problems with crime. Conviction rates for crimes investigated by the FBI and passed along to US attorneys offices are low and in many areas, crime on native communities is deprioritized by local law enforcement.

“This is a problem and you’re not even the first FBI official that I’ve had this conversation with in this room or over at Homeland Security. This is not new,” Heitkamp told Johnson heatedly. “This problem is not new and I would suggest that maybe if you want to come here and offer solutions, maybe the best way would have been to pull a couple case files and say ‘What went wrong?'”

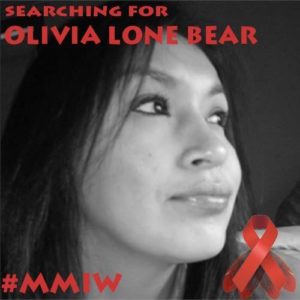

She suggested that they look at the case of Olivia Lone Bear, whose body was found in a North Dakota lake in August. Montana Sen. Steve Daines (R) asked about Ashley Loring HeavyRunner, a college student who disappeared from the Blackfeet Reservation more than a year ago.

The trouble is, there are far too many names of the missing, and still, too few answers.