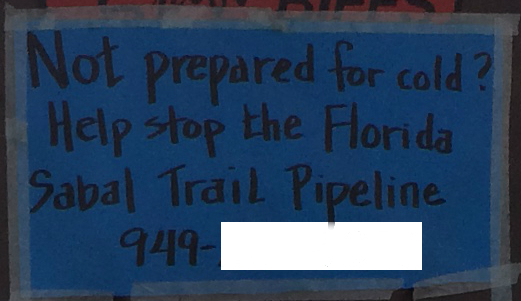

“Not prepared for cold?” the sign reads, “Help stop the Florida Sabal Pipeline.” The posting was one of several stuck to message boards and buildings in the Sacred Stones protest camp in North Dakota, near the Dakota Access Pipeline. With winter beginning and temperatures dropping, some of the protesters are considering leaving the camp for warmer climes, and one group is hoping to persuade them to join another pipeline protest further south.

Set to be completed in 2017, the Sabal Trail Pipeline will carry natural gas through Alabama and Georgia into central Florida, where it will be used to generate electricity. Ground has already been broken on the project and work is proceeding rapidly. In March, the company obtained a certificate of public convenience and necessity from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), which allows it broader leeway to use eminent domain to acquire land needed for the project.

In Florida, the protesters are divided between three camps: Sacred Water, Water is Life, and Crystal Water. Still, the group is far less organized and has far less support than the DAPL protests. The group posted on its Facebook page on Wednesday that construction near the Crystal Water camp was nearly complete because “there was almost no support there. Only one #WaterProtector that I know of [showed up].”

When InsideSources called the number posted in North Dakota, it was answered by Zac Raskin. Raskin, a Florida native, says that he was born near the area where the pipeline would run. Like the protesters further north, he worries that pipeline spills could contaminate what he calls “the richest area in the world for water.”

Despite his efforts, the Florida protests remain largely amorphous, independent groups operating in different parts of the state. Raskin says that he is working to develop a broader organization to allow them to work together. The Florida protests are much smaller than those in North Dakota. One event earlier in the month, which Raskin called “pretty successful,” drew around 50 people, but for the most part the group does not have the numbers to do much more than stand with signs on the side of the road.

Although signs about the Florida pipeline have been posted in the Sacred Stones camp, so far few people have been interested in learning more. Raskin says that while he received a handful of calls, only one person ventured down from North Dakota to help out.

Lacking the numbers and publicity that kept Sacred Stones in the headlines, the protesters in Florida have taken to protesting on the side of highways and outside of Sen. Marco Rubio’s office. Another group is looking to halt construction by “installing an art project called the Blued Trees Symphony” that would in effect copyright the ground as a piece of artwork in order to prevent its eminent domain seizure.

Still, the protesters in Florida realize that the project has already been fully approved and “there is no more asking nicely from elected representatives.” And with all the focus on DAPL, it is hard even for them to gain publicity for their cause.