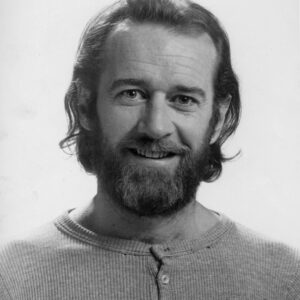

Watching the new Judd Apatow and Michael Bonfiglio two-part HBO Max documentary was a great time-traveling ride. From the hippy-dippy weatherman on the “Ed Sullivan Show” to hosting the first SNL episode to playing the genial conductor on “Shining Time Station,” the decades flashed before my eyes in “George Carlin’s American Dream.”

And for me, it brought back memories of my work on a legendary case that the Supreme Court should have refused to hear.

That’s because there’s lots of attention in the documentary devoted to Carlin’s hit records, which remain cherished albums in my well-stocked vinyl collection. One notable track was from his stand-up routine — “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television.” These “seven dirty words” (Google them), according to Carlin, could not be aired by broadcasters regardless of the context or time of day.

And when WBAI-FM, a counter-culture radio station licensed to the Pacifica Foundation, broadcast in full a companion track (“Filthy Words”) on his follow-up album, “Operation Foole” (ironically during a discussion on contemporary language boundaries), the Carlin assertion of a clear forbidden line was put to the test legally for the first time.

In 1973, John Douglas, an active member of Morality in Media, filed a written complaint with the Federal Communications Commission, stating that his 15-year-old son had heard the broadcast on his car radio while they were driving around New York City around 2 p.m. Douglas indicated that this was inappropriate and asked that the FCC look into the matter.

Following Pacifica’s investigation and written response, the FCC issued a declaratory order that upheld the Douglas complaint but withheld any penalties against the station. This put WBAI on notice that “in the event subsequent complaints are received, the Commission will then decide whether it should utilize any of the available sanctions it has been granted by Congress.” This meant that the FCC could impose fines on the station or even revoke its license to operate in the future.

The cloud that hung over the station due to this “raised eyebrow” of the FCC led Pacifica to appeal the order in federal court. It argued that the FCC’s application of an “indecency” standard, which unlike obscenity, was not prohibited by law, violated the broadcaster’s freedom of speech under the First Amendment. The FCC argued that it had the authority to set content boundaries for what it deemed indecent since it was authorized to grant and renew broadcast licenses by the Communications Act of 1934.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit found Pacifica’s argument to be persuasive, and in a 2-1 decision by a three-judge judicial panel, ruled that the FCC had violated the First Amendment by issuing its warning based on “indecent” programming.

Unexpectedly, the FCC decided to press on by appealing that decision to the Supreme Court. The Department of Justice, which typically would handle such an appeal, refused to do so since it agreed with the lower court’s reasoning. That left the FCC to go it alone.

As a summer associate in Washington between my second and third years at Berkeley Law, I found myself suddenly transformed from someone who played the Carlin records over and over to working on the legal brief to convince the Supreme Court not to hear the appeal at all — since the FCC’s position could not be squared with established freedom-of-speech precedents under the First Amendment. That’s the personal aspect that played in my mind while watching the powerful documentary.

Alas, I was part of a losing team since the Supreme Court accepted the FCC’s appeal and agreed with it in a 5-4 ruling, which has given the regulatory agency the power to decide what is indecent in broadcasting ever since then (with some flexibility for late-night programming that Congress later authorized).

In recent years, the Supreme Court has had two cases that allowed it the opportunity to revisit the FCC’s authority to punish broadcasters for fleeting expletives and nudity under the rubric of indecency. But unlike a second federal appeals court, this time in New York, which again found the FCC’s actions to violate the First Amendment, the Supreme Court ducked the constitutional issue in favor of a narrower procedural decision that enabled the broadcasters to escape the FCC’s wrath in these instances.

Imagine what George Carlin would have to say about that now. The chain of events that he unwittingly unleashed continues to remind us that the American Dream he championed remains one that still is very much worth fighting for.