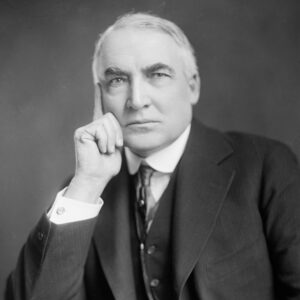

The fallibility of expertise is obvious when one considers that for nearly a century historians have considered Woodrow Wilson among the near-great presidents and Warren Harding among the worst. (Harding died 99 years ago this month, and Wilson six months later.)

In 1921, Harding gave the most courageous presidential civil rights speech ever. Speaking in Birmingham, Ala., Harding called for racial equality. White spectators stood in stunned silence while Black spectators cheered. Civil rights pioneer W.E.B. Dubois called the speech “a sudden thunder in blue skies” driving discussion “into the clear light of truth.”

In contrast, Wilson, Harding’s predecessor, helped poison race relations for a century. Even by 1910’s standards, Wilson’s racism was appalling. As president, he strived to undo whatever modest gains African-Americans had made since the Civil War.

Harding openly supported anti-lynching legislation — which Wilson opposed. Wilson’s acolytes whispered (falsely) that Harding had an African-American ancestor; Harding’s response amounted to “maybe so, and I don’t care.”

Wilson invited Hollywood pioneer D.W. Griffith to screen his technically pathbreaking but thematically toxic “Birth of a Nation” at the White House — the first film to be shown there. The film featured Wilson’s words: “The white men were roused by a mere instinct of self-preservation … until at last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan, a veritable empire of the South, to protect the Southern country.” (Wilson later developed misgivings about the film, but his screening had already helped revive the Klan.)

Historians often favor leaders with expansive agendas during dramatic times over those with modest goals in calmer times.

Wilson led America into World War I, sired the Federal Reserve, and exerted an imperious (“Wilsonian”) foreign policy. Harding wasn’t a great president, but his America craved “normalcy” after the nightmare of World War I. Wilson expanded the federal government, while Harding focused on the less sexy goal of tidying it up. Today’s Office of Management and Budget and Government Accountability Office trace their origins to Harding. Harding’s appointees were often outstanding— Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover and Chief Justice William Howard Taft.

Wilson’s venality and Harding’s generous nature were not limited to race.

Wilson’s 1912 Socialist opponent, Eugene V. Debs, was imprisoned for urging resistance to World War I conscription. Wilson wrote, “This man was a traitor to his country and he will never be pardoned during my administration.” From prison in 1920, Debs ran against Harding, who then commuted his sentence and invited him to the White House, saying, “I’ve heard so damned much about you, Mr. Debs, that I am now glad to meet you personally.”

Wilson ignored warnings that draconian punishment of Germany would elicit disaster. Fury over his Versailles Treaty was a catalyst for Germany’s monsters — anarchists, communists, proto-Nazis. Wilson excluded senators from negotiations over the League of Nations, and they rejected his brainchild. Harding involved senators deeply in negotiations over a postwar disarmament treaty and won unanimous Senate approval.

Harding signed the unfortunate 1921 Emergency Quota Act closing America’s doors to immigration. But the act passed nearly unanimously in both houses — more a product of Wilson-era xenophobia than of the newly inaugurated Harding.

Immensely popular while in office, Harding’s posthumous reputation suffered from his naïve trust of unworthy cronies. Interior Secretary Albert Fall was imprisoned for corruption. Harding’s corrupt attorney general, Harry Daugherty, was forced from office by Calvin Coolidge, Harding’s successor. But were Fall and Dougherty worse than Wilson’s attorney general, A. Mitchell Palmer, who whipped up the first big Red Scare, deported immigrants and launched raids of dubious constitutionality against Americans? Harding’s posthumous reputation also suffered from the (correct) rumor that he fathered an illegitimate child with a much-younger woman.

Harding was what Winston Churchill called Clement Attlee: “a modest man with much to be modest about.” Compare that to a story told by Sigmund Freud: an associate remarked to Wilson how proud he was to have contributed to the president’s election victory. Wilson’s icy response, Freud said, was: “Remember that God ordained that I should be the next president of the United States. Neither you nor any other mortal or mortals could have prevented this.”

Rest well, Mr. Harding.