Poor William Rosecrans was having a tough time in 1863.

He was a Union general during the Civil War with two pressing problems. First, Abraham Lincoln was riding him hard because he hadn’t driven the Confederate army out of Tennessee. But that was child’s play compared to his other dilemma: What to do with all those prostitutes?

Nashville was a major Union base. Millions of dollars worth of guns, ammunition, food. and uniforms were stored there. Thousands of soldiers guarded those stockpiles, too.

The law of supply and demand ruled. All those soldiers (most in their 20s), far from home and with dollars in their pockets, created the demand. And swarms of practitioners of the world’s oldest profession descended on Nashville to supply their services. The 1860 Census identified 200 “working girls” in the city; by 1863 they were pushing 2,000.

The prostitution epidemic was more than a moral issue. In that age before penicillin and other antibiotic treatments, STDs were running rampant through the army. Nashville’s hospitals were overflowing with men infected with various “social diseases.”

By July, Gen. Rosecrans, nicknamed “Old Rosy,” had enough. He ordered Nashville’s provost marshal to “seize and transport to Louisville all prostitutes found in the city or known to be here.”

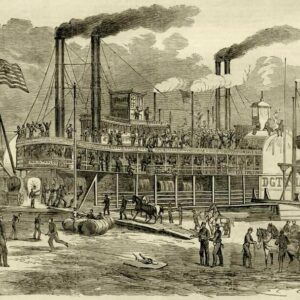

On July 9 the Provost Guard, the Civil War version of today’s Military Police, rounded up the first 111 hookers they founded and herded them onto the steamboat Idahoe. (Yes, that is the correct — and ironically apt — spelling.) They included teenagers, one woman in her 70s, and every age in between.

The women were understandably furious. So was the Idahoe’s captain. His boat was brand new, and the army had commandeered it over his irate protests.

The Ihadoe was stocked with three days’ provisions. Louisville was a good destination, the provost marshal said, but he didn’t particularly care where the women wound up. So, with a sullen captain at the wheel, dozens of angry women screaming curses, and countless onlookers taking in the carnival scene from the riverbank, history’s first Love Boat set sail.

And that’s when the fun really started.

Soldiers on board had to keep a constant eye peeled in both directions: Making sure women didn’t jump overboard while also making sure men didn’t swim out and climb aboard. (Some women solicited business to guys onshore).

Bad news travels fast, the saying goes. When the Love Boat reached Louisville, city leaders rowed out to meet it and said, “You’re not dumping them here!” Sheriff’s deputies waited with shotguns at the landing to back them up. The Idahoe couldn’t even dock for supplies.

She headed upriver to Cincinnati where the same thing happened. “There is not much desire on the part of our authorities to welcome such a large addition to the already overflowing numbers engaged in their peculiar profession,” The Cincinnati Gazette huffed.

The Love Boat’s odd odyssey was national news. Papers along the Ohio River followed its movements, eagerly reporting every lurid detail in Victorian rapture. A Cleveland newspaper wrote, “The majority are a homely, forlorn set of degraded creatures… they managed to smuggle a little liquor on board, which gave out on the second day. Several became intoxicated and indulged in a free fight, with knives being used.”

The woebegone captain set course for St. Louis. This time the mayor sent a delegation that met the boat long before it even came close to that city with the simple message, “You’re not going to make Nashville’s problem our problem.”

Eventually, the Idahoe had nowhere left to go but home. In August, she deposited 98 women (there’s no word on how 13 vanished along the way) back in Nashville where it all began.

An army inspector found the Idahoe’s stateroom “badly damaged, and all the mattresses severely soiled.” The captain was paid the equivalent of $86,000 in today’s dollars to cover the destruction, and–according to the official report—for food and “medicine peculiar to the women of this diseased class.”

Rosecrans solved his army’s STD outbreak with innovation. Figuring “If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em,” he required all prostitutes to get a license as a “Public Woman” to work in Nashville, plus undergo a weekly physical examination by an army doctor for 50 cents per visit. Diseased hookers were sent to a special military hospital for medical treatment. If a soldier patronized an unlicensed prostitute, or if one was found working without a license, it was 30 days in jail. The program cost $6,000 to operate and took in $5,900 in fees, almost paying for itself.

In less than a year, STDs dropped dramatically among both prostitutes and their patrons. Rosecrans didn’t realize it, but he had inadvertently stumbled upon an innovative idea.

He was one of America’s first practitioners of public healthcare.